A salt substitute to lower stroke risk?

New provocative research on the science of salt

It’s taken for granted by many of us that reducing salt in the diet means better heart health.

After all, we see a recommendation to reduce sodium intake from the American Heart Association, the USDA, nutritionists, the WHO, and basically anyone with a public profile and an opinion on the matter.

This goes double if you have a heart condition.

But you might be surprised to learn that some really smart people have been questioning this wisdom.

A look at sodium consumption across the world by Sripal Bangalore and Franz Messerli suggests that higher sodium intake is associated with a longer lifespan (yes, you read that correctly, more salt is associated with less death).

The low quality of data has led to so much uncertainty regarding the relationship between reducing sodium and congestive heart failure that we see commentary on the need to study this better from Clyde Yancy in JAMA Internal Medicine.

As with so many things, when you dig deep into the research on nutritional recommendations, you often learn that “the science” isn’t quite as settled as we might like to believe that it is.

The fact that a controversy like this can exist is why it’s so important to do the high quality research that can support our recommendations.

I’ve written before about how difficult it is to do nutritional research and how we should demand a higher level of evidence before making our “official” medical recommendations to the public.

And so I’m really excited to be able to talk about a fascinating study that was just published looking at the impact of a salt substitute on the risk of stroke.

Swapping out salt for a salt substitute lowers the risk of stroke

The SSaSS trial (Salt Substitute and Stroke Study - adding trial there is sort of redundant but using it makes the sentence flow better) was a cluster randomized, controlled trial assessing the impact of a salt substitute on risk of cardiovascular events.

For the study, 600 different villages in rural China were randomly assigned to a group given a salt substitute that was 75% sodium chloride (table salt) and 25% potassium chloride and a group that was not given any salt substitute.

They studied people who either had a history of stroke or who were over age 60 and had high blood pressure.

The participants given the salt substitute were instructed to use the salt substitute as they would normal salt.

They followed the people for a few years and measured their rates of stroke, heart attack, and death (all important things to consider). This is an important distinction, because trials in the past have only looked at the impact of salt substitutes on blood pressure, not the hard endpoints that we really want to know about.

Now, blood pressure matters - don’t get me wrong - but we care less about the blood pressure numbers themselves and more about the way that high blood pressure impacts risk of heart attack and stroke. After all, the drug atenolol lowers blood pressure but doesn’t seem to reduce the risk of stroke.

We know that the folks in the treatment group used the salt substitute because their urine was tested and found to be higher in potassium and lower in sodium than the group that didn’t get the salt substitute.

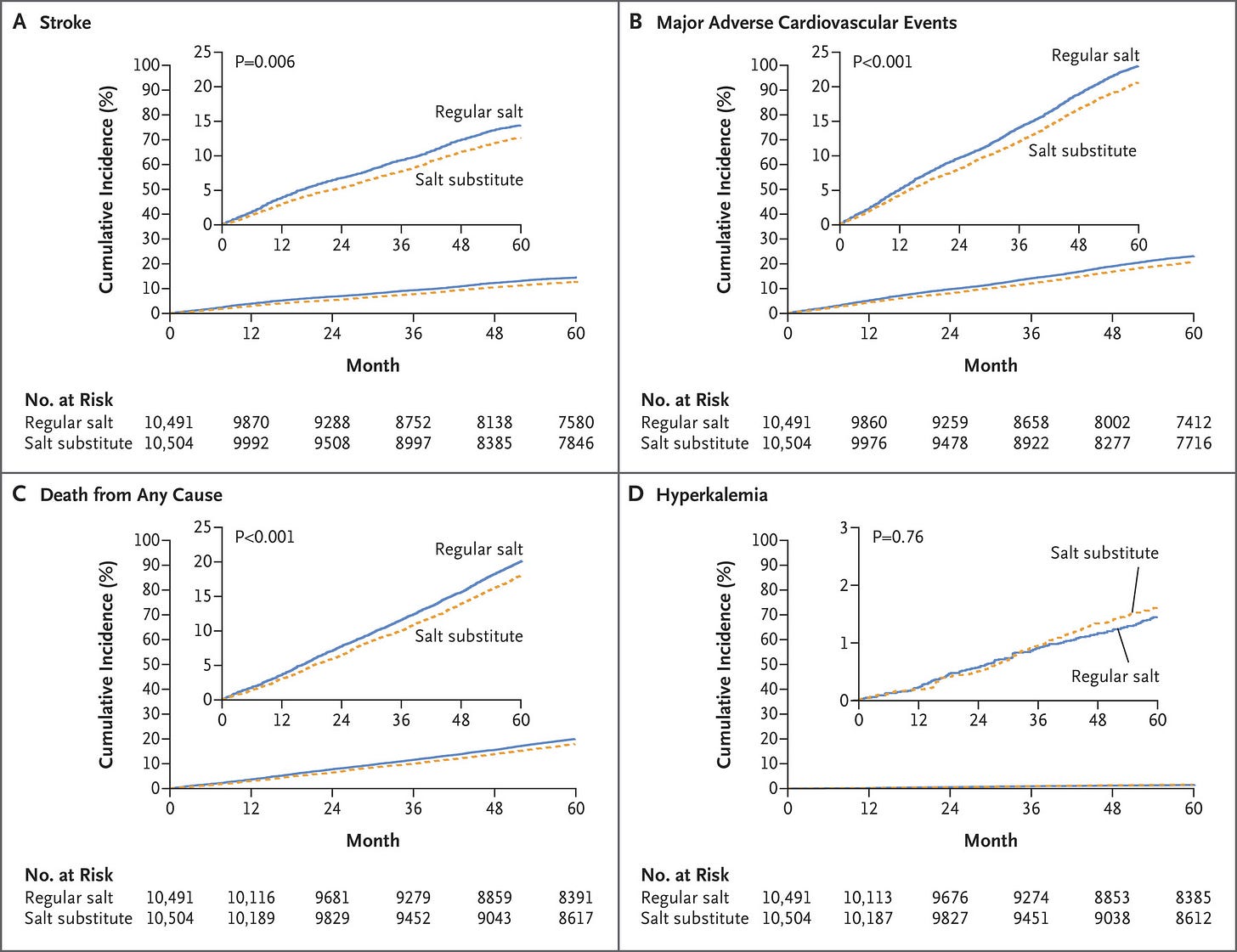

The findings were surprising to me - in a good way. Compared to normal salt, the group that used the salt substitute had:

Fewer strokes

Fewer heart attacks

Less death

Look here - the different between the groups is increasing over time, suggesting a cumulative and additive benefit that may continue to increase over time:

This is a big deal! It’s hard to see results like this with a medication. It’s really hard to see results like these with a nutritional intervention.

The concern with a salt substitute containing potassium is that you run the risk of raising potassium levels dangerously high, a concern that’s particularly present for people who have kidney disease - so people were excluded from this trial if they had bad kidney problems.

Why haven’t I heard about this?

I have no idea!

Maybe because most media didn’t cover this study - I couldn’t find a write up in the New York Times, CNN, the Washington Post, Fox News, Business Insider, Bloomberg, or any other mainstream outlet (although the Washington Post did write about why they’re only published recipes with sea salt rather than other types of salt).

The trial was covered by some medical publications, but nothing that broke through into the mainstream.

That sucks.

I guess we’d rather hear the same redundant COVID information than legitimately novel research that has real world impact.

This is an important trial looking at a vital public health question.

What does it mean in real life?

That’s the million dollar question.

Does this trial mean that reducing sodium can save your life? That’s certainly one way to spin the results.

But keep in mind, this trial tested a salt substitute (75% sodium chloride, 25% potassium chloride), not sodium reduction per se.

It’s impossible to know whether the effect seen in these people came from reducing sodium, adding potassium, or a combination of the two.

We’ve already seen in other trials that there’s a suggestion that potassium intake may be a more meaningful predictor of cardiovascular events than sodium intake.

And so while we can’t tease out the benefit of what specifically drove the results here, I do think that there’s something to be said for considering a 75/25 salt substitute, because that’s the intervention that they used in the study.

Now, some caveats before you throw out your salt and replace it with a salt substitute:

The study was done in villages in rural China, so you can question how applicable this might be to someone from a different demographic who lives in a different setting

The patients in this study were fairly high risk - many of them had previous strokes and many others had poorly controlled blood pressure. If your risk is lower than that, the expected benefit from an intervention like this is probably less as well.

Most of the sodium in our diets comes from processed foods, not the salt that we add to the food we prepare - a big contrast from the group in this study, who consume essentially nothing processed. Using a salt substitute as only fraction of your salt replacement is likely to confer only a fraction of the benefit.

I think this is a really exciting trial. I learned a lot from reading it and I think there are some lessons here for all of us.

The next step is to test this in a population comparable to ours and see if the results can be replicated.

In the meantime, I think that watching your sodium intake (particularly from processed food where it isn’t balanced out by potassium) and trying to eat plentiful vegetables and fruits - natural sources of potassium - makes a ton of sense.

Thank you for reading! Please share on social media and encourage your friends and family to subscribe!