Another COVID Q&A

With conflicting information about COVID everywhere, even the experts don’t know what to do. And to top if off, many of the physicians who are on the news as “experts” don’t take care of patients and haven’t stepped in an ICU for a decade, so it’s hard to consider their recommendations reliable.

As a result, I figured I’d do another Q&A today since I’ve been getting so many questions about COVID particulars.

My antibody test came back negative and I’m pretty sure I had the virus. What’s the deal?

We are seeing incredibly confusing antibody test results, even from tests that sound reliable (and there is a considerable range in both agreement and accuracy of these tests).

I’ve even seen cases of spouses that both got infected at the same time, with positive nasal swab test results that had different antibody responses.

If you think you had the virus and your antibody test came back negative, there are a handful of possibilities.

You didn’t actually have the virus

You had the virus and you didn’t mount an antibody response

You had the virus and your antibody production has not yet ramped up. This could happen if you have an antibody test too close to your actual infection.

You had the virus, you developed antibodies, and the test didn’t pick them up. This is a false negative

You had the virus, you developed antibodies, and the test looked for the “wrong” kind (i.e. IgG vs. IgM). This is another false negative.

We still don’t know what an antibody response says about immunity. Or what it says about your ability to infect others.

If I’ve already had the virus, do I still need to wear a face mask?

I think that you should.

We don’t know enough about how long someone infected can spread the virus. I’ve seen nasal swabs come back positive in patients more than a month after initially testing positive. Until proven otherwise, we have to suspect that positive nasal swab means you can spread infection.

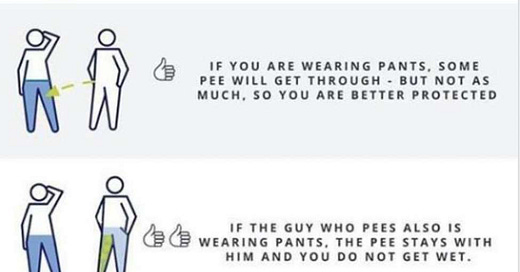

In my opinion, masks are as much about protecting others as they are about protecting yourself. The urine test (stolen from Reddit) makes this explanation simple.

Can you address combining bubbles?

This is a strategy that’s being employed in New Zealand, which seems to have had success combating the virus.

The premise is that if your household is isolated and your friend’s household is isolated, you should be able to spend time all together, potentially even sans social distancing.

This makes sense as long as the bubbles don’t continually interact with other bubbles.

Like many aspects of life, this strategy is only as strong as its weakest link. If one member of the bubble gets sick, all bubbles that interact have potential to be infected.

Ultimately, if both groups have been isolating well, I don’t envision why this would be a problem. But it’s a slippery slope, and I worry that combining bubbles is like giving a mouse a cookie.

If remdesivir blocks the replication of the virus, would taking a prophylactic dose be helpful for the population?

This seems to me to be a bad idea.

First, any medication will have side effects, and something prescribed widely to people at low risk is going to likely cause more harm than good'.

Second, I would worry about viral resistance to the drug when taken widely. Think about the concept of antibiotic resistance. We want to avoid giving drugs whenever we can to reduce this risk.

Third, I don’t know how long we would have to treat people for. Weeks? Months? Years? Seems like an expensive way to try to reduce viral spread with an unclear benefit.

If I go for a run, do I need to wear an N95 mask?

There’s a lot of speculation about the distance that respiratory droplets can travel. Wired wrote a whole article on it.

I’m not going to get into the kinetics of viral transmission when released from a moving body, but I suspect that with conservative behavior, you can get away without wearing the N95 for your whole run.

The evidence is mounting that viral spread is far less outdoors than indoors, for a number of different reasons. So synthesizing that information with the concept that respiratory droplets may travel farther from a moving object, give us some simple principles.

When you’re doing something active, observe a larger than 6 foot boundary between yourself and a person around you. 12 feet is probably good.

You don’t need to wear a mask if you’re the only person you can see.

Getting outside more rather than less is probably good for you

So realistically, when will society be opened up?

I think this is going to be dependent on how well we reduce spread of the virus. As many have pointed out, reducing viral burden on society as quickly and efficiently as possible is probably the fastest path towards economic recovery.

This is going to require collective action and a lot of inconveniences to our lives for a prolonged period of time.

Have you ever heard of the shopping cart theory?

The premise is that putting back a shopping cart is an easy, but slightly inconvenient act that we all recognize it’s the right thing to do. While you should be able to return your cart in all but the most dire of emergencies, there is no punishment or fine to you for not returning it. You gain nothing by returning your cart, but collectively we all benefit if carts are returned.

This is similar to the daily inconveniences of reducing spread of SARS-CoV-2. Each individual must take actions that are slightly annoying but pretty easy to do - wearing a mask in public places, washing hands, avoiding big crows - to maximize societal benefit.

The fact that many stores need to employ individuals to put back shopping carts should make us all stop and think.