What happens if you get COVID?

It’s probably the most important question you need to answer when making your own individual decisions about going back to work, going to the grocery store, or just going about your life.

Once you ask that first one, a lot of other questions start to follow, and pretty quickly the avalanche of unknowns and terrifying possibilities can get overwhelming.

Are you going to die?

Are you going to end up in the hospital? In the ICU? On a ventilator?

Are you going to be permanently disabled from lung scarring?

Are you going to get a blood clot?

Are you going to have a stroke?

Are you going to get your family sick?

Since we have a lot more data available that the last time I wrote about these numbers, I thought it might be worthwhile to revisit things now.

How likely are you to die if you get COVID?

Even now, this isn’t an easy question to answer.

Across the US, about 4.4% of confirmed cases have died - 133,000 deaths out of 3 million confirmed infections. This number is called the case fatality rate, or CFR. And it’s important to remember that the death counts we’re seeing, even as terrible as they are, may be underestimating the true number of deaths from SARS-CoV-2.

This does not tell us about your individual chances. Remember, this is confirmed cases not total cases. In case you haven’t been paying attention, our testing is still not as good as we’d like it to be (both in quality and in quantity), so we don’t truly know the number of cases that we’ve had.

What we really want to know is the IFR, or infected fatality rate.

The problem is, this is really difficult to calculate. A large part of the problem has to do with our inadequate testing, but part of the problem is that many infections - possibly as many as half - are totally asymptomatic.

The other part of the equation is that an overall societal IFR tells you little about your own personal risk, because it’s merely the number across the population rather than one targeted to your own personal risk.

When we’re calculating any percentages of total infections, there’s unfortunately going to be a necessary amount of fuzzy math.

So how can I figure out what this means for me?

There’s no perfect dataset to figure this out.

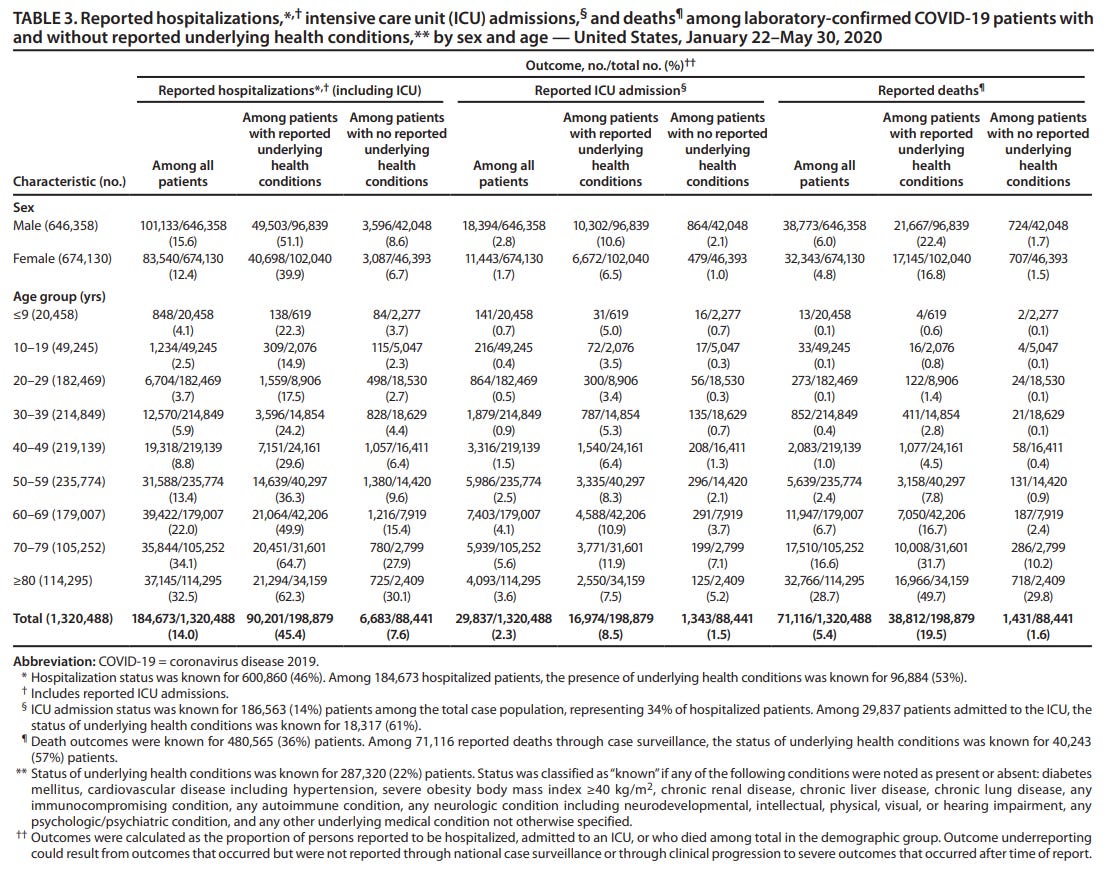

I spent some time looking through published CDC COVID data to try to answer these questions. Admittedly, these statistics are already a bit obsolete (only including information obtained up to May 30), but I think it’s probably the best overall data that we have.

The official statistics have tons of holes. There’s quite a bit of uncertainty regarding hospitalization status and underlying health conditions. But these statistics, as limited as they are, paint a picture that isn’t super reassuring.

I’m including the table from their data below the newsletter text that I think is most illustrative of what we should be thinking about.

Keep in mind, these data are not about total infections, but are just about cases.

Data on underlying health conditions

Having an underlying health condition - any underlying health condition - puts you in a different risk bucket than someone without any. The conditions that are grouped together by the CDC data include:

“diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease including hypertension, severe obesity body mass index ≥40 kg/m2, chronic renal disease, chronic liver disease, chronic lung disease, any immunocompromising condition, any autoimmune condition, any neurologic condition including neurodevelopmental, intellectual, physical, visual, or hearing impairment, any psychologic/psychiatric condition, and any other underlying medical condition not otherwise specified.”

How much higher is the risk?

Risk of hospitalization with underlying condition - 45.4%

Risk of hospitalization without underlying condition - 7.6%

Overall risk of hospitalization among all-comers - 14.0%

Risk of death with underlying condition - 19.5%

Risk of death without underlying condition 1.6%

Overall risk of death among all-comers - 5.4%

That means underlying health conditions increase risk of hospitalization by almost 600% and risk of dying by over 1000%. It’s no joke.

Data on age

We’ve all heard about how age is the biggest risk factor for death from COVID. Looking at the CDC data a bit more closely suggests that age really is a huge driver of risk, and not just because age is associated with all the underlying health problems.

How much higher is the risk? Let’s look at hospitalization and death numbers the CDC put out.

People age 30-39 are hospitalized 5.9% of the time and die 0.4% of the time

People age 70-79 are hospitalized 34.1% of the time and die 16.6% of the time.

There’s a gradation in these numbers with each decade, but the overall trend is fairly consistent (see the table below or click on the link to view data in more detail).

How should we adjust this based on the crappy testing?

This is really the million dollar question. Because testing has never been done in a widespread fashion to really get a sense of the true poportion of patients who have asymptomatic disease and thus never come to medical attention, we’re left with inferences based on epidemiologic reports and serologic studies.

If you look at the seroprevalence in a place like Spain, which was ravaged by the pandemic and had over 28,000 deaths, only 5% of the population have antibodies against SARS-CoV-2.

This isn’t the level you’d hope to achieve herd immunity, and it isn’t the level you’d hope to get a sense of comfort that the IFR is way below the CFR.

I suspect - and this is my guesstimate based on what I’ve read and opinions of other experts - that between 1/2 and 1/10 people become cases rather than infections.

In other words, I believe the CDC numbers overestimate the actual individual risk from COVID by a decent margin. We’re probably missing between 50 and 90% of all infections, so the numbers go down by a decent amount.

So if the CDC overall case fatality rate is 5.4%, the real number is likely under 2.7% and may be as low as 0.5%.

I think if you take the CDC numbers for your age/demographic numbers and divide by 2, you probably get somewhat close to your overall high end risk. If you divide by 10, you probably get somewhat close to your overall low end risk.

Caveats abound

Obviously, my numbers are guesses based on the actual data and inferences from other things that I’ve been reading. This is not medical advice and the possibility exists that I could be wildly off with my estimates.

I’ll end with my 5 steps of advice to prevent infection:

Wear a mask

Wash your hands

Don’t touch your face

Wear a mask!

Wash your hands!

PS: If you’re finding value in my newsletter, please share with friends and family and encourage them to subscribe here:

CDC data table referenced above: