Clinical trials I'm thinking about this week

It’s been a busy week in the hospital for me, so we’re doing something a bit different for this week’s newsletter.

I’m going to do a quick roundup of a few of the important clinical trials that have been applicable to some of the patients that I’ve been seeing this week with a bit of editorializing on what they mean and the impact on my thinking.

Not everything you’ll read below is all that new - I’m a big believer that physicians are often better served re-reading a trial that we know is important than just focusing on the shiny new thing that everyone’s talking about.

But there’s obviously a balance to strike with keeping up to date on the important stuff, so we’ll start with something contemporary.

Does Ozempic help treat heart failure?

One of the hardest conditions to treat in medicine is heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

The history of clinical trials for this condition is littered with disappointing results (at least until the SGLT2 inhibitors came along), partly because HFpEF is a heterogeneous group that probably has a number of pathologies that cause the same end result.

The STEP-HFpEF trial is a recently published proof of concept trial suggesting that Ozempic (technically Wegovy with the dosing here, but they’re the same thing) may have a benefit in this group of heart failure patients, showing a short term improvement in things like quality of life and distance covered during a 6 minute walk test:

It’s another big time positive result for the GLP-1 agonists (albeit in a short term trial without hard endpoints like hospitalizations or death).

When you consistently see a benefit across different conditions with a class of drugs, it’s a sign that the medication has broad applicability and that doctors are going to be bullish on prescribing it.

We saw this over the last few years with the SGLT2i inhibitors (drugs like Farxiga and Jardiance), which have a benefit in diabetes, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease.

Expect to see and hear even more about the GLP-1 drugs (even though we’ve been hearing a lot!) as we get more and more data on different use cases.

And the questions that come up now are really interesting too - is HFpEF a metabolic disease? A complication of obesity?

It’s too soon to draw definitive conclusions, but here’s my clinical intuition from taking care of lots of these patients.

There’s a subset of HFpEF patients who have symptoms related to fluid retention from weight gain (when you gain weight, especially if your insulin levels are high, you often end up retaining salt and water).

There’s also a subset of HFpEF patients whose symptoms are mediated by physical deconditioning that started when they started having heart failure symptoms. The way that our vasculature and skeletal muscles work in conjunction with the heart is really important and when people stop moving, lots of problems happen.

Feeling sick means less movement, and less movement means feeling sicker. It’s a vicious cycle.

A drug that helps weight loss makes it easier to move. More movement makes symptoms better, which makes it easier to move more. Moving more helps with weight loss, which helps with fluid retention, which helps with symptoms. And the cycle continues.

Like many things in medicine, there can be a snowball effect in both directions.

The most vulnerable time for patients is right after a big medical event

Looking at the shape of a Kaplan-Meier curve in a clinical trial tells you a huge amount about the natural history of a disease process.

One of the most important trials in all of cardiology is a study from 2001, called the CURE trial.

CURE looked a the impact of clopidogrel (also known as Plavix) on patients coming in with heart attacks. This is the trial that helped to establish the benefit of treating heart attack patients with two different medications that block the function of platelets, colloquially known as DAPT (dual anti-platelet therapy).

When I re-read this trial, I focus on what the Kaplan-Meier curves look like, which you can see here:

The Y-axis is a composite endpoint of a bunch of bad cardiac things (death from cardiovascular causes, nonfatal heart attack, or stroke) and the X-axis is time.

You see that the first few months are the time when risk increases the most. There’s the sharpest increase in bad outcomes. After 3 months, they certainly continue to go up, but the rate that they go up starts to slow.

If you look at a lot of other trials of patients after heart attacks (PLATO, TRITON, ISAR REACT 5, etc), you’ll quickly notice that the curves all look the same. Risk is highest up front and then tapers off.

Right after a heart attack is when people are most vulnerable. There’s something different about the biology that makes people more inflamed, more likely to have blood clots, and more likely to have bad things happen.

The longer you get out from an event, the less additional risk you have. And so that means that up front, especially after a cardiac issue, the important of optimizing treatment early has significant benefit.

But the broader point - if you look at the shape of the curves, you can often understand what happens with the disease - is applicable to many problems other than treating heart attacks.

There’s no rush to do invasive procedures on a patient who has stable heart disease

The ISCHEMIA trial asked a different type of question than most clinical trials ask.

Most research asks a question about the impact of one treatment compared to another treatment.

ISCHEMIA asked a question about a treatment strategy - for patients who have stable but high risk heart disease, is there any benefit from an early invasive strategy versus a more conservative strategy?

The answer to this question is sort of in the eye of the beholder.

On one hand, there was no reduction in death from taking patients for stents up front:

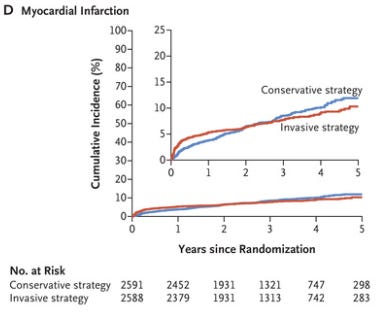

But on the other hand, heart attacks were reduced over the long term by doing the invasive approach early:

My take home from ISCHEMIA is that it’s reasonable to go in either direction, especially if you can engage a patient in a shared decision.

There’s certainly no rush to do something invasive, because the curves take two years to cross (and an invasive strategy probably carries up front risk).

But the key to remember here is that the ISCHEMIA trial isn’t looking at all patients with heart disease - if the trial wouldn’t have enrolled your patient, then you need to exercise a lot of caution before you extrapolate the results to be applicable.

Who doesn’t ISCHEMIA apply to? A few really important groups:

Anyone with new or progressive symptoms of heart disease

Patients with repeated hospitalizations or recent heart attacks

Patients who have heart disease that might be better served with bypass surgery (they did CT scans on most patients to ensure they didn’t have heart disease best dealt with surgically)

Knowing how to apply data is as important as knowing what the data shows.