COVID-19: the great unequalizer

Michael Scott once described pizza as the great equalizer: Rich people love pizza, poor people love pizza, white people love pizza, black people love pizza.

It makes sense that a virus like SARS-CoV-2 should be a great equalizer as well. After all, we can all be exposed, we can all be infected, and we can all die from this disease. But as this pandemic has ravaged society, we’ve seen that the way that COVID-19 wreaks havoc is anything but equal.

It turns out that this virus is nothing like pizza. Well, apart from both being bad for us.

COVID preys on us very unequally. And we should all be alarmed at what this reveals about society.

Some populations have a much higher mortality from COVID than others

A recent paper from the Journal of the American Medical Association attempted to quantify and understand some of the racial health disparities that we have been seeing with COVID:

In Chicago, Illinois, rates of COVID-19 cases per 100 000 (as of May 6, 2020) are greatest among Latino (1000), African American/black (925), “other” racial groups (865), and white (389) residents. Mortality rates are substantially higher among African American/black individuals (73 per 100 000) compared with Latino (36 per 100 000) and white (22 per 100 000) residents. New York City (as of May 7, 2020) reported greater age-adjusted COVID-19 mortality among Latino persons (187 per 100 000) and African American individuals (184 per 100 000), compared with white (93 per 100 000) residents.

In other words, African Americans and Latinos have twice the death rate of white in New York City and Chicago. It’s unreal.

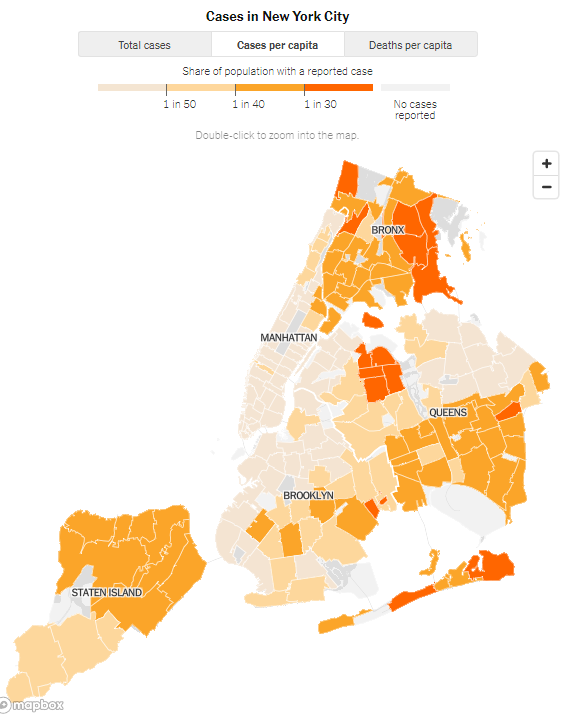

The disparities can also be visualized geographically. Take a look at this heat map of infections in New York City:

These differences are striking. And it’s easy to brush them off as related to socioeconomic status, especially when you look at the NYC map. But it seems like these differences can only partially be explained by socioeconomic status.

Quick detour about why socioeconomic status would even matter

It’s well described in the medical literature that the social determinants of health - things like your economic stability and education level, even the neighborhood that you live in - play a huge role in our likelihood of developing diseases and our outcomes once we do develop disease.

This is part of why doctors do something called “taking a social history” when you’re seeing them. Traditionally, social history is thought of as focused on the use of substances that can be harmful to health - tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs - but social history really needs to incorporate things like occupation, housing situation, costs of medications and treatments, travel difficulties, and whatever related individual difficulties a patient may have in either accessing care or adhering to prescribed medical therapies.

Understanding a patient’s social determinants of health will help to understand how likely they are to require hospitalization, have exacerbations of disease, and even die.

What explains the racial differences?

A disparity like this is clearly multifactorial. The authors of the JAMA article suggest two important factors.

The first is that racial and ethnic minorities have a higher burden of chronic diseases that increase risk of dying from COVID - things like diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, HIV, obesity, and asthma.

The second is best described by Clyde Yancy: “social distancing is a privilege.”

This means that when you only have one home, you can’t escape to your country house if you live in the city. It means that when you work as a cashier in the grocery store, you don’t have the luxury of taking Zoom meetings from your couch.

The possibility of genetic or biologic factors of course is always something to consider, but I tend to find genetic explanations of racial differences among disease to be both unpersuasive biologically - there is more genetic diversity across a race than there is between races - and unpersuasive psychologically - you can’t untangle differences between groups of people unless you dig into the historical events that might impact current group differences.

[If you’re really interested in the nature vs. nurture debate on race, check out this debate between Ezra Klein and Sam Harris.]

A crisis reveals who we really are

When we are faced with challenges, the nature of who we are is revealed. What the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed about the injustices of our health care system should make us all outraged.

In the context of the things that we already know about racial inequalities, Dr. Yancy argues that the only surprising thing here is that we’re surprised at all.

Consider the aggregate of a higher burden of at-risk comorbidities, the pernicious effects of adverse social determinants of health, and the absence of privilege that does not allow a reprieve from work without dire consequences for a person’s sustenance, does not allow safe practices, and does not even allow for 6-foot distancing. The consequent infection and death rates due to COVID-19 complications are no longer surprising; they should have been expected.

The COVID pandemic hasn’t created these disparities, but rather has both further exposed and heightened them. I’ll conclude this newsletter installment with another quote from Dr. Yancy:

These observations are rooted in the recalcitrant reality of the deeply entrenched history of health care disparities and may settle as the most painful example yet of the regressive tax of poor health. COVID-19 has become the herald event that now fully exposes the deep and chronic social wounds in US communities.