A lot of people have been asking me about the experience of taking care of COVID patients who are sick enough to end up in the ICU and require a ventilator, so I wanted to write a bit about the nuts and bolts of caring for these patients in the ICU.

Most people with COVID-19 take a while to have real respiratory deterioration. We’re commonly seeing patients with symptoms for a week or more before oxygen levels start to drop and the oxygen through a nasal cannula isn’t doing the job anymore. It’s only when we’ve exhausted all of our noninvasive options that we even consider the possibility of putting someone on a ventilator.

Putting Patients on a Ventilator

The medical term for the process of putting someone on a ventilator is intubation. Just the act of intubating a COVID patient is a high risk endeavor, with risk for both the patient and the health care provider. In a non-pandemic, intubation is performed with direct visualization of the larynx and vocal cords in a patient who is pre-treated with oxygen being pushed into their lungs using a bag valve mask as seen here.

The bag valve mask helps to boost a patient’s oxygen levels as high as possible before the breathing tube is inserted. During that process a patient who requires a lot of extra oxygen can’t get any while the tube is being placed, so under normal circumstances pre-oxygenation is a vital part of the process. Unfortunately, for COVID patients, a bag valve mask aerosolizes the virus and puts people in the room (even if wearing adequate PPE) at increased risk. As a result, we’ve been avoiding it, which means that a patient’s oxygen levels can drop dangerously low.

Once that scary hurdle has been cleared and the breathing tube has been successfully inserted, there’s still a lot of work to be done.

Sedating patients on the ventilator

The acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) in COVID patients requires a type of ventilation known as low tidal volume ventilation, which means small breaths of air to avoid causing damage from high pressure in lungs that are filled with fluid.

Imagine how you feel after running up stairs - you’re starved for oxygen and incredibly short of breath, and all you want is to gulp in air as quickly as possible. Low tidal volume ventilation prevents the big breaths of air you crave because they can cause high pressure injury to the lungs. So instead of being allowed to take full, deep breaths, patients on the ventilator are given short, shallow breaths. It’s no surprise that most of these patients will have difficulty becoming synchronous with the ventilator and thus have difficulty with adequate ventilation.

As a result, we end up needing to use lots of medications to sedate COVID patients when they’re intubated. There are multiple classes of sedative medications that we use when people are on a ventilator. The ones that you’ve probably heard of are opiates - like morphine and fentanyl - and benzodiazepines - like valium and xanax. We also commonly use propofol - the heavy sedative that probably killed Michael Jackson from an overdose.

We usually require two medications in patients being sedated on a vent, but with COVID, we’re seeing a startling number of young and obese patients who may require more sedation than usual. This means that there are plenty of patients in whom we are using 3 and even 4 sedatives. In my hospital, we’ve started to run out of some of the standard meds that we would use, and I’ve had to use ketamine in certain circumstances, which is a heavy anesthetic medication that’s also used as a street drug with the moniker “Special K.”

And in some cases, despite maximum doses of 4 different sedatives, a patient is still having difficulty with the low tidal volume ventilation, so we need to add medications that completely paralyze the patient, which adds an additional layer of complexity to the management of these already critically ill patients.

Keeping patients on a ventilator alive

Many of our sedatives have a side effect of dangerously lowering blood pressure and patients will often require medications to raise blood pressure as well as frequent checks of their oxygen levels. These tasks require two special types of IV lines to be placed in patients - central lines and arterial lines.

A central line is a long catheter (catheter is just the medical word for tube) that gets placed under sterile technique in one of the major veins in the body - the jugular vein (in the neck), the subclavian vein (right below the collarbone), or the femoral vein (in the groin). This can provide a way to give medications that raise blood pressure when it drops dangerously low - these medications cannot be given through a standard IV because they can cause a risk of cutting off oxygen supply to a limb if the IV has problems.

An arterial line is a special type of IV that’s placed in an artery (most commonly the radial artery in the wrist) so that frequent checks of the blood levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide can be performed without constantly sticking more needles in to draw blood.

What if the ventilator isn’t enough?

As we’re working to adequately sedate these patients and support their blood pressure, we’re simultaneously trying to make sure their oxygen levels are adequate despite the diffuse and massive lung damage from COVID. If making maximum ventilator adjustments doesn’t work, we will try to prone the patient - putting them on their stomach, as I had discussed on a previous email.

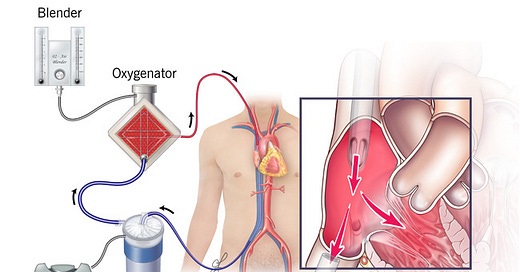

If we’re still failing to adequately provide oxygen due to massive lung involvement, we have one last option to consider something called extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), which basically means you take all their blood out through one of the large veins in their body (usually the leg), add oxygen with a machine, and then replace the newly oxygenated blood into another large vein (see below picture).

ECMO is only an option for very few patients as hospitals have very limited amounts of the necessary equipment and an invasive procedure like this carries potential for complications that makes it too risky for most patients apart from those who are young with minimal other medical problems.

And there are some patients who have such severe lung disease that despite all of our attempts at heroic medical support, we can’t provide sufficient oxygen because of their overwhelming infection, and they die anyway.

Patients with COVID are generally requiring a ventilator for long periods of time, in many cases more than 2 weeks. Each day on a ventilator comes with additional risk of complications - from the vent itself, from the medications we are using, from a worsening underlying infection. And many of these patients end up needing a tracheostomy - a surgical procedure to insert a tube in their neck that can provide long term ventilator support.

So the decision to say, “yes, I want to be intubated if I’m sick enough to need one” carries with it a lot of hurdles - it’s not as simple as just putting a breathing tube in and then taking it out when the infection is over.