Does Covid increase heart attack risk?

It’s almost taken as a given that a Covid infection increases the risk of heart attacks, because, after all, that seems to be what the data show:

If you read Eric Topol:

“It’s an inconvenient truth that Covid is associated with an excess of heart attacks and strokes beyond the first month of infection. That can no longer be ignored or refuted.”

You can read paper after paper describing this impact, and they all tell the same story: that even long after you’ve had Covid, your risk of heart attacks increases by a nontrivial amount.

But… (to paraphrase Bill Simmons) are we sure that Covid really increases the risk of heart attacks months after we’ve been infected?

Color me skeptical. In fact, I am completely unpersuaded by this data.

Let me show you why.

Let’s look at the data showing Covid increases heart disease risk

All of the papers that look at this are basically the same. They all take data from people who had a positive Covid test or a chart diagnosis of Covid and then compare them to matched controls.

Most of the papers also do statistical analyses to adjust for age, sex, and other medical problems, a technique called “propensity matching.”

The seminal paper that’s quoted by most here is an analysis from Ziyad Al-Aly of over 150,000 veterans with Covid compared to control groups.

They looked at charts from the VA and found patients who had positive Covid tests and then compared them to similar people who didn’t have positive Covid tests.

[Note: they didn’t look at patients who had negative tests, just patients who didn’t have positive ones]

They found that the risk of all kinds of cardiovascular problems increased in veterans who had Covid compared to age and sex matched controls, with higher risk for sicker patients (i.e. patients who ended up in the ICU had a higher risk of these problems than patients who weren’t hospitalized):

According to this data, the increased risk appears similar for strokes, heart attacks, pericarditis, irregular heartbeats, heart failure, cardiac arrest, blood clots. It’s about a 1.7-fold increased risk of heart attacks and a 1.6-fold increased risk of stroke.

Other studies show a similar relationship between a positive Covid test and a higher risk of cardiovascular problems.

Here’s one looking at claims data from private insurance companies that assessed patients who had an ICD-10 code in their medical chart to signify a positive Covid infection:

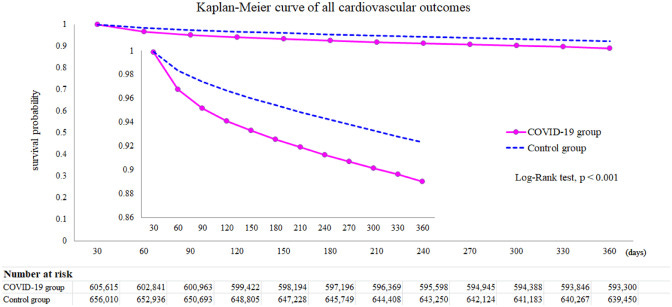

And here is a study looking at patients who had positive Covid tests compared to patients who had negative Covid tests. They found a higher risk of heart disease in people who had Covid compared to controls matched for age, sex, and other chronic medical problems:

This data is incredibly flawed. It’s so flawed that I don’t think you can draw conclusions from it

On one hand, you can look at this data and say that it all tells the same story in different ways, strengthening the case that Covid infection does increase the risk of heart attacks and strokes.

And all of these studies show risk in the same direction with a similar order of magnitude.

But there are flaws in each of these analytical methods.

Take the VA study. If you find patients with a positive Covid test in the chart and compare them to patients who don’t have a positive Covid test, does that really tell you anything about whether the Covid infection caused the outcome you’re studying?

How do you know that the patients who don’t have positive Covid tests in the chart never had Covid? Maybe they did and just didn’t get tested… how many people do you know who never reported their positive tests to a healthcare organization because they didn’t feel that sick?

Is it possible that there’s something different about people who seek out healthcare when they have symptoms of a possible infection, like that they’re a bit sicker than people who don’t seek out healthcare?

Or if you became sick enough with your Covid infection to end up seeking out healthcare, or even worse, you ended up hospitalized or in the ICU, does that suggest you might have a higher burden of chronic disease than someone who doesn’t get that sick?

Take the private health insurance claims study. If you are looking at claims data on either an ICD-10 diagnosis of Covid or a lab test documenting Covid, you run into similar potential confounders as the VA study - i.e. there may be something different about the people who end up with a chart recorded diagnosis of Covid or get a Covid test than people who didn’t.

And by subjecting your analysis to ICD codes, you introduce a huge potential for inaccuracy:

Anyone who has worked in the health care system or a hospital knows that there’s a lot of garbage in the chart that doesn’t match up with a person’s actual diagnosis.

The people who have the most chart diagnoses are often people with the most chronic illness.

The heart attack question, in particular, is one that I see miscoded in the chart really frequently. One of the ways that we evaluate whether someone has a heart attack is by seeing elevated markers of a protein named troponin in their blood. But an elevated troponin by itself doesn’t equal a heart attack:

The last study comparing people who had a positive Covid test with people who had a negative Covid test, seems like the best one.

After all, it looks at people who had Covid tests and compares the ones with positive tests to the ones with negative tests.

In theory, this would eliminate some of the confounding that occurs if you only look at people who had positive tests because they were sick enough to seek out care.

But if you read the methods of the article, you’ll see:

“The COVID-19 group consisted of people who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. The people in the control group tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 and did not show any symptoms of COVID-19.”

And so immediately we’re left with a clear confounder - people who tested negative were people who didn’t have symptoms. That means they were likely people who were tested because they had to be tested for a different reason rather than people who had an illness and came to medical attention.

There’s too much potential for confounding with all of these studies for me to take their results as even close to definitive.

It’s not just that the data are mediocre, there also isn’t a plausible biologic mechanism

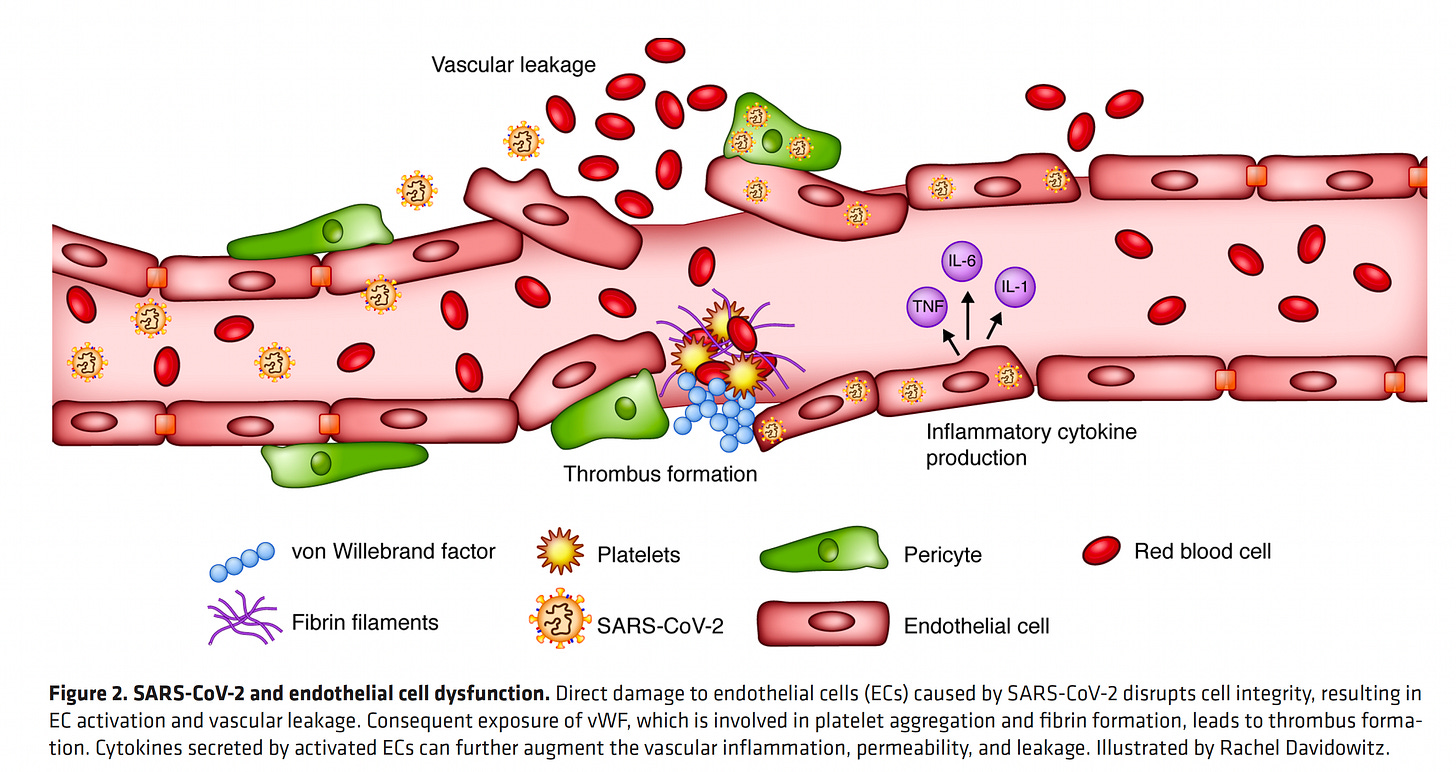

In Eric Topol’s Substack, he proposes the the mechanism of Covid-induced increased cardiovascular risk is blood vessel injury and propensity towards clotting:

As far as a mechanism for the excess of late (beyond 30 days from Covid) major cardiovascular outcomes, it has been well established that there is both endothelial lining of blood vessels) inflammation and the inter-dependent or direct hyper-coagulability that can be induced by Covid. That is to say, there are multiple paths by which Covid predisposes towards clotting. And microclots are one of the mechanisms that have been identified as an underpinning for some people suffering from Long Covid. Here’s a good graphic to illustrate pro-thrombotic endothelial dysfunction induced by SARS-CoV-2:

But I don’t find this mechanism plausible to explain cardiovascular complications long after Covid infection.

Here’s the problem with that proposed mechanism: it requires vascular injury induced by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and the virus is cleared from our system when people are over the infection.

For this mechanism to be plausible, you would need to have ongoing viremia (virus in the bloodstream) causing ongoing injury to the blood vessels.

When we’re done with an infection, the inflammation comes down because our immune system has cleared out the virus.

I don’t find it plausible to think that the risk of a heart attack is increased for a year after a Covid infection.

So, the data are confounded and there’s no plausible mechanism. But also, the numbers aren’t believable

Does it pass the smell test to believe that someone has a 70% increased risk of a heart attack for a year after a Covid infection?

If so, why aren’t heart attacks, strokes, and cardiovascular problems all increased by tens or even hundreds of thousands of cases after the millions of Covid infections that we’ve seen?

The American Heart Association data showed an increase in heart disease over the first year of the pandemic, but nowhere near a 70% increase (actually under 7%).

And you have to remember that those numbers are confounded by the way that healthcare services have been disrupted during the pandemic.

The magnitude of the effect in these papers compared to the actual statistics that are being reported just aren’t believable.

My take on the bottom line - what you’ve heard about Covid and long term heart disease risk is fear mongering

I don’t see any signal persuade me that there’s a big increase in risk of a heart attack long term post Covid.

The data that we have on increased risk are hopelessly confounded to the point of not being worth thinking about.

The biological mechanism is implausible.

And the actual numbers of heart disease don’t fit with the proposed increase.

So if there is any increase in heart disease risk from Covid, it’s very likely to be much smaller than has been suggested based on what you’ve read and what’s been reported.

And, more likely, in my opinion, there is no increase in long term anything after you’ve cleared the infection.

But if you really do believe the data, then you should be asking everyone whether they’ve ever had Covid as you try to assess cardiovascular risk.

The only problem is that pretty soon, everyone will have been infected, and so everyone will need additional screening to account for their 70% increase in heart attack risk.

The logic gets pretty absurd if you carry it out to the natural conclusion.

And so I will counsel my patients post Covid infection exactly the same as I counseled them before.

Whether you’ve had Covid isn’t an important part of the cardiovascular history. And anyone who tells you otherwise isn’t really basing it on hard data.