Dr. Oz, crudité, and admitting when you're wrong

Correcting the record on my time working for Oz

If you haven’t seen the viral Dr. Oz video on crudité, you’re missing a piece of performance art.

This video has received a ton of earned media. If you haven’t seen it yet, I think it’s worth 38 seconds of your time:

For me, personally, the most entertaining part of this video was actually the name that he called the grocery store. The store is Redner’s, which he called Wegener’s.

Most media coverage has suggested that he mixed up Wegman’s and Redner’s, but my suspicion is that he was actually using the eponym of a medical condition that used to be called Wegener’s granulomatosis. The preferred nomenclature is now granulomatosis with polyangiitis (or GPA), because Friedrich Wegener was a Nazi.

So while the media coverage has been focused on how out of touch Oz is with the average grocery shopper, I think this is also evidence that he’s out of touch with medicine.

Why am I writing about this? I’m sure you could read a more entertaining take on Oz in New York Magazine

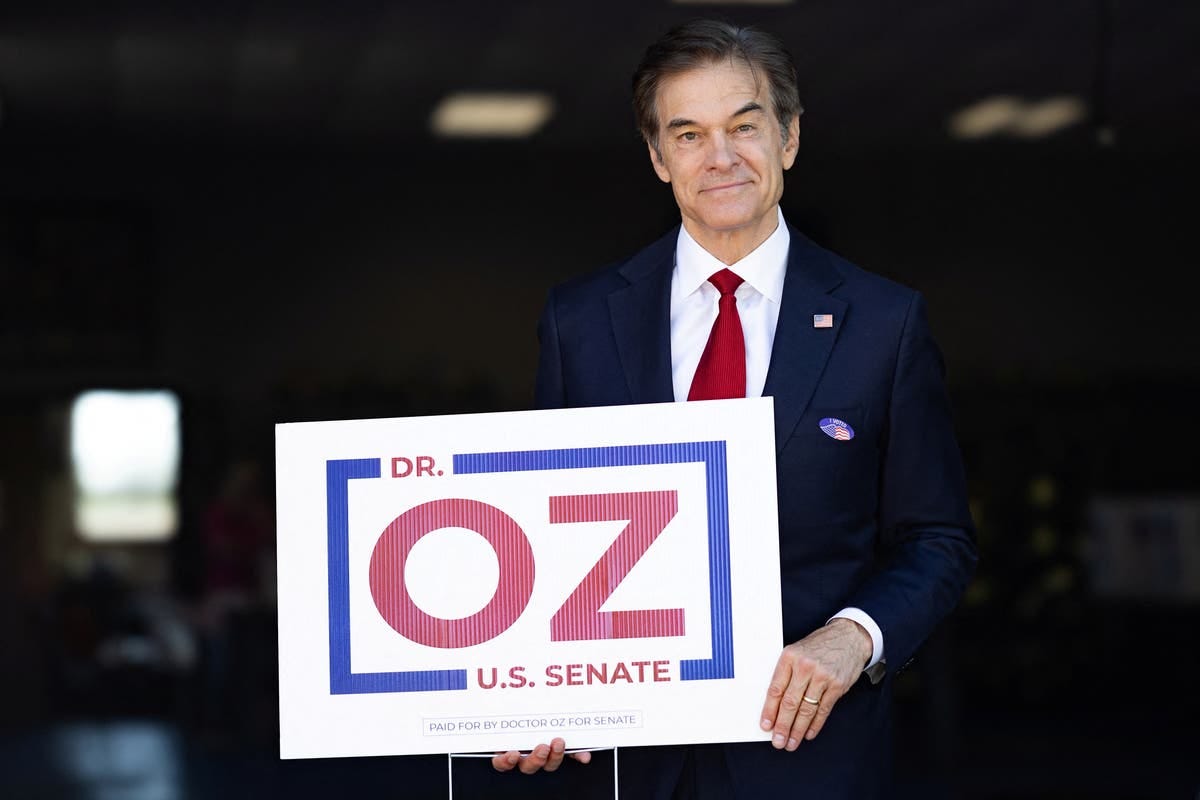

After Dr. Oz announced he was running for the United States Senate, I wrote a fairly lengthy newsletter talking about my time working for his show.

The newsletter came off as pretty complementary of Dr. Oz when you read it.

I wrote about Oz behind the scenes, what he taught me, and what I learned from working for the show. I also wrote about the criticisms that I faced in academic medicine about my work on the show as well as how I defended that time.

And as I’ve had time to reflect on that newsletter, I think that my overall assessment was probably wrong - the way I balanced the good and the bad was simply too forgiving.

My defense of the good parts of the show is partly based on subconscious self preservation - after all, I spent a year of my life working there, and had to defend myself time and time again on interviews and with my colleagues.

I think it’s only natural that I’m a bit defensive about what I did, and, I guess, about Mehmet Oz as a boss and a person.

So, you can think of this newsletter installment as another episode of “what I learned from Mehmet Oz and his show,” except I won’t obscure the negative by focusing solely on the positive.

It’s bad to mislead people, and it’s especially bad if you’re making money by misleading them

One of the things that I left out of my last newsletter was some of the insight we got from focus groups on how they thought about Dr. Oz and the rest of the medical system.

Many of our viewers felt that Oz was the only one who had their backs, while their other doctors wanted to push pills and procedures.

And so, being the staff of his TV show, we wanted to do lean into this myth - that Dr. Oz is the hero crusading against a corrupt medical system to save our audience.

The Oz brand emphasizes solutions, but not the solutions that have been robustly shown to have benefit in clinical trials, because those require a doctor’s appointment and a prescription or procedure.

There’s an old joke about alternative medicine: what do you call an alternative treatment that’s been proven safe and effective? Answer: a medical treatment. In other words, if something really is shown to be a good treatment, most doctors use it because we want to help our patients.

On the show, however, we’d focus on the things that “Oz found” that YOU can do without a doctor’s help - the supplement you can buy being the most common solution we offered.

I wrote in my last newsletter:

“The job of the medical team at the show is to find evidence that might support the suggestion of a benefit of each of our solutions.

We would often look for a mechanistic study showing that so-and-so supplement worked in vitro (or in lab animals) along with evidence that it appeared safe in human studies. We would then extrapolate those findings with the suggestion that it might work in humans as the justification to put something on the show.

Nothing was totally made up. It was all based on a kernel of truth, a study showing this mechanism, an epidemiologic association demonstrating that connection”

The end result is that we convinced a lot of people to waste a lot of money on things that we all knew wouldn’t help them.

Oz himself would always report that he wasn’t endorsing any specific products or selling anything himself, but it seems that the real truth here is a bit murkier than that.

And regardless, even if you’re not selling the products directly, when your platform is build around offering solutions that don’t work, you’re making money by misleading people.

When you’re a public figure, the “real you” isn’t who you are in private

I really liked working with Oz when I was at the show.

He’s smart, engaging, and warm. He treats people well. He asks incisive questions. He dealt in nuance for almost everything behind the scenes.

He even has a good sense of humor.

There’s a reason he’s made it to the level he has - he’s brilliant, engaging, charismatic, and charming.

So it’s a bit jarring to see a side of someone that is smart and nuanced contrasted with a side that’s full of crap.

When the smart and nuanced side is in private and the full of crap side is in public, it’s tempting to say, “but that’s not who they really are.”

But as I’ve had time to reflect on it, I think that’s the opposite of correct. When you have a public facing role, what you say in that public role is who you actually are.

If you tell people on your show to buy raspberry ketones as a “the number 1 miracle in a bottle to burn your fat,” but behind the scenes know that “there’s not a pill that’s going to help you, long-term, lose weight, live the best life without diet and exercise,” the real you is the one telling people to buy the raspberry ketones.

When you’re a physician making recommendations to people who trust you about their health, the real you is the one who is making those recommendations; it isn’t the person who asked a smart question about the confidence intervals in a pre-show briefing.

And it doesn’t matter how you feel about that:

“When I feel as a host of a show that I can’t use words that are flowery, that are exultatory [sic], I feel like I’ve been disenfranchised, like my power’s been taken away,” said Oz. “You don’t want to be on a pulpit talking about how passionate you are about life and thinking, ‘Well, if I use that word it’s going to be quoted back to me.’”

When you have a platform and an audience that trusts you (especially an audience that spends their limited finances on the things that you recommend), the words you choose matter.

The biggest surprise that I’ve had on Oz’s political career: he doesn’t seem to connect with people

Mehmet Oz’s superpower was always the way he connected with his audience.

It was amazing to see how much our audience loved him. When he did health fairs, or blood pressure screenings, the connection with the people was pretty special.

And so when people asked me if I thought that Dr. Oz really believed all of the things he was saying as a politician, my answer was basically, “I don’t know, but I wouldn’t be surprised either way.”

I suspect that he really believed in some of the things that we hyped on the show. But he really thought that some of them were nonsense. Despite that contradiction, his enthusiasm was the same regardless of what he really thought.

So it didn’t surprise me that he would say things - as many politicians do - that he may or may not truly believe in.

What shocked me was the way that he hasn’t seemed to connect with voters, because hosting an hour-long show for over 10 years is a remarkable achievement that speaks to Mehmet Oz’s connection with his audience.

My work on the show taught me that the messenger matters much more than the message when it comes to motivating and inspiring people.

To watch this campaign flounder from afar has been surprising to me, because I thought that the connection Oz has with his show audience was going to translate seamlessly to the general population.

The bottom line: I was probably wrong about how I wrote about my experience

In my last newsletter, I wrote about the good that we did at the show: the Pap smears that people got, the folks who lost life-changing amounts of weight, or the cutting edge science that we were able to highlight.

In doing that - and in closing with the fact that “it wasn’t all negative, and I certainly stand by that” - I didn’t really give the appropriate level of seriousness to the harm that Dr. Oz and his show have done to the audience and to the scientific discourse.

Just because I’m defensive about being personally criticized doesn’t make the end product better.

But I won’t continue to rationalize to myself that the work was a net good for the world. And so I’ll finish up here with the two important lessons that I’ll take with me as I’ve had time to reflect more on my time working for Mehmet Oz:

First, it’s bad to mislead people about what’s good for their health, and it’s particularly insidious to use the trust that people have in you to give them bad recommendations.

Even if you try to balance things with important and true information, it doesn’t excuse the harm that’s done.

And second, when you have a platform that influences people, the “real you” is what you use that platform to promote, it’s not the smart questions that you ask behind the scenes.

I decided to post this before my usual Friday morning timing, but next week we’ll go back to Friday mornings for this newsletter.

Thank you for reading! Please share with friends and family and encourage them to subscribe!