When I was a second year resident, I spent a month working in the emergency room at Bellevue Hospital.

One of my co-residents and I played a morbid game during some of our more chaotic overnights - we would bet on the proportion of people triaged to “side 3” of the emergency room who were there for alcohol-related reasons.

The alcohol group was never less than 50% of the people there, which really blew me away at the time.

This rotation came at a time in my medical training when I was really obsessed with the problem of medical waste; this is the hundreds of billions of dollars a year we spend on medical care that doesn’t make anyone live longer or feel better.

When I started my emergency room rotation, I was laser-focused on the way that we should be rigorously implementing judicious medical testing in the form of the “Choosing Wisely” campaign.

I remember in particular, being annoyed that we always had to order a “lipase level” on each patient that came in reporting pain in any location from pelvis to shoulders in order to look for inflammation of the pancreas, which can be a sign of a scary disease called pancreatitis (which happens to be alcohol-related).

Then I saw a couple of patients get pretty sick with pancreatitis when I would have blown off their symptoms based on my history, and I realized something important: I’m not as smart as I thought I was.

But beyond the lesson in hubris, after I spent some time overnight working on “side 3,” I learned a couple of other very important lessons:

The trajectory of illness can be unpredictable - you miss things when you prematurely close on a diagnosis before you’ve completed a workup

Risk can be asymmetric - the risk of ordering an extra lab can certainly lead to wasteful spending and unnecessary downstream testing, but in the acute setting, you don’t want to miss a life-threatening diagnosis that has a finite window of opportunity to intervene

Alcohol is really bad for you, and we underplay the personal and societal risks of drinking too much

Alcohol causes problems both directly and indirectly

During our game about alcohol-related emergency room presentations, I quickly learned something that I’d read before but never internalized: in addition to causing almost 100,000 excess deaths a year, alcohol plays a gigantic role in societal crime.

As much as 1 in 4 crimes are committed by someone with alcohol in their system, as are a disturbing proportion of murders and sexual assaults.

In the emergency room, we saw people who had been attacked or had done the attacking themselves (and were in policy custody at the time of their emergency room evaluation).

We saw people who had accidents, falls, and who had fallen asleep on the street.

We saw a lot of drunk people brought in for just being way too intoxicated who were given beds in order to “sleep it off.”

And we also saw people who had serious medical problems caused by alcohol.

These alcohol-induced problems can take an acute form, like pancreatitis, alcohol withdrawal, or alcoholic hepatitis. They can also take a chronic form, like cirrhosis, cardiomyopathy, or cancer.

The crazy stories tend to be the alcohol-adjacent emergency room visits - like the patient who was attacked by his drunk partner in a fit of jealousy when she caught him cheating, leading facial trauma and a globe rupture after she smashed a highball glass on his eye.

But the more common alcohol related problems are the indolent ones, and awareness about the impact of our own alcohol use here is important.

And so while the goal of this newsletter isn’t to ruin your holiday fun, I do think it’s worth spending most of this holiday newsletter on the problems that I see pretty regularly caused by alcohol.

Alcohol affects the heart and vascular system in a number of important ways

I’ve written a newsletter the last couple of years on holiday heart syndrome - the irregular heartbeats, heart attacks, and sudden deaths that occur during the holiday season, at least some of which is alcohol related.

But alcohol causes problems year round. There are a number of heart problems that I see regularly throughout the year that are significantly impacted by alcohol use:

Alcohol is a clear trigger for atrial fibrillation. The effect is dose dependent and happens fairly quickly. Atrial fibrillation is a common irregular heartbeat that increases risk of stroke and often necessitates prescribing blood thinners to lower that risk

Alcohol raises blood pressure, which increases long term risk of heart attack and stroke. I’ve been struck by quite a few patients who have come off a couple of blood pressure medicines when they decided to cut back on alcohol use.

Alcohol disrupts sleep, which impacts mood and chronic disease risk. Alcohol is paradoxical in this way since many people use alcohol as a sleep aid. But even though it functions as a sedative, helping people to fall asleep, alcohol leads to fragmented sleep and blocks our bodies from getting REM sleep.

Most people who drink alcohol everyday would see improvements in their health from drinking less.

Some of those improvements may be quick - better sleep, improved mood, less palpitations - but some of them may take some time to manifest.

Alcohol doesn’t get enough blame as a public health hazard

Alcohol use causes 1 out of 8 deaths in people from the age of 20-64.

Some of this is direct, in the form of alcoholic liver disease or alcohol poisoning, but some of it is due to motor vehicle crashes, accidents, suicide, and homicide.

The numbers here are both staggering and depressing:

There are a lot of good public health ideas about how to reduce the negative impact that alcohol has, and I would recommend this article by Matt Yglesias if you’re really interested in diving into the public policy here.

But I don’t want you to confuse one point that I’m making here - that alcohol is a big public health problem - with an accusation that any amount of drinking is terrible for you.

Alcohol use is like many things - it follows a Pareto distribution

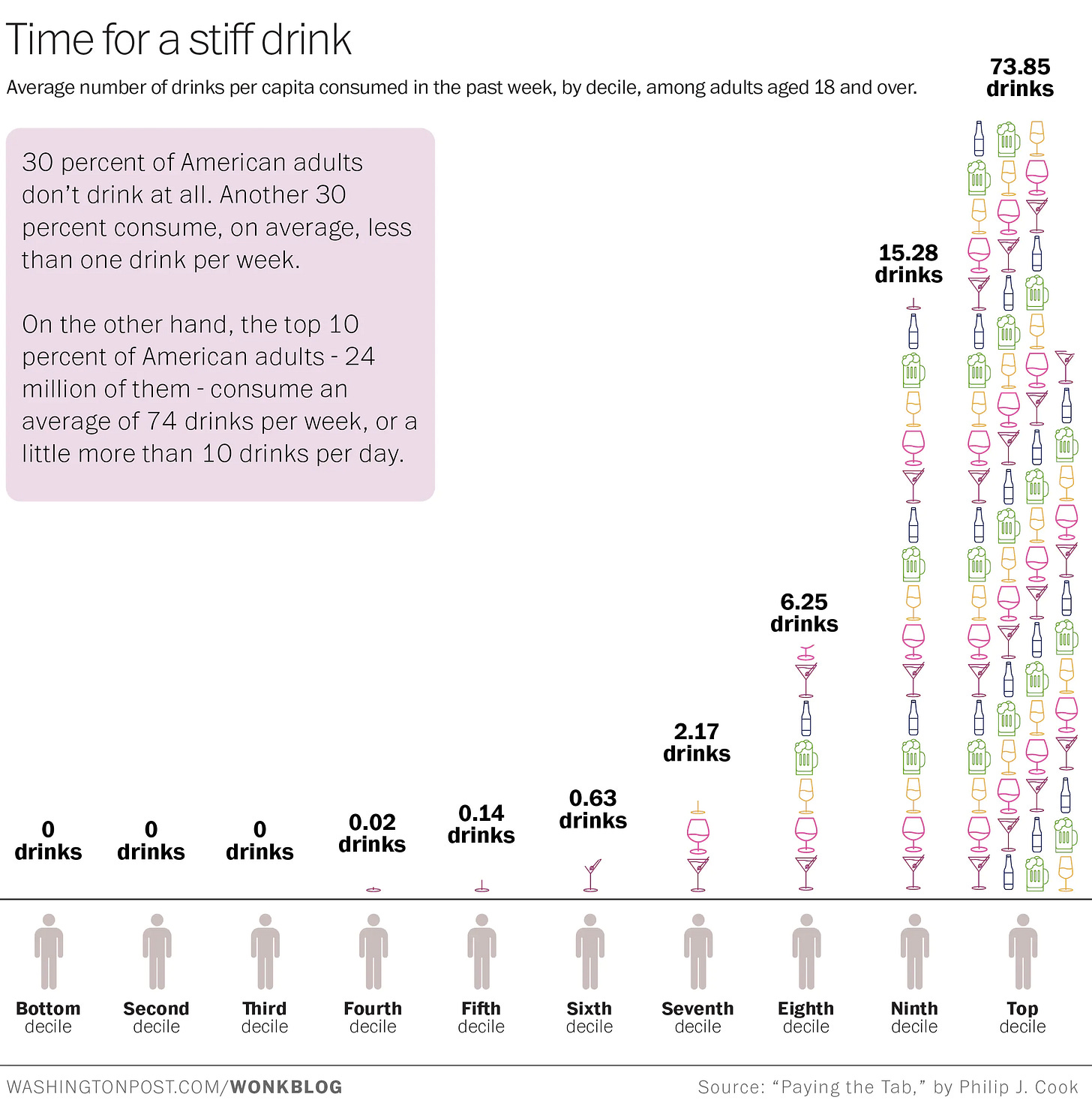

A Pareto distribution means that a minority of people are responsible for the majority of outcomes here - in the case of alcohol, the top 10% of drinkers consume well over half of all alcohol.

The harms from alcohol are disproportionately borne by the folks who drink the most, which is a tiny proportion of the population:

Most people barely drink, and even those who drink more than 80% of the population don’t really drink more than is considered safe.

The Pareto distribution of alcohol consumption means that public policy efforts to reduce alcohol use for the heaviest drinkers may mean problems for the bottom line of the companies who make booze:

"One consequence is that the heaviest drinkers are of greatly disproportionate importance to the sales and profitability of the alcoholic-beverage industry," he writes writes. "If the top decile somehow could be induced to curb their consumption level to that of the next lower group (the ninth decile), then total ethanol sales would fall by 60 percent."

I’ll add the obligatory warning I make about the holidays each year: holiday weight gain explains most weight gain

The average person gains about a pound over the holiday season and doesn’t lose it the rest of the year.

That’s enough to explain a 10 pound weight gain between age 30 and age 40, and another 10 pounds by age 50, and so on. You can extrapolate from there.

Even if your weight stays stable the rest of the year, a bad holiday season coupled with age related loss of muscle mass explains a fair amount of excess adiposity as we age.

The annoying lecture here writes itself - drink with moderate, be careful about weight gain - but that’s not the message I want to send

The point isn’t to become a teetotaler, skip the holidays, do a fasted HIIT workout on Christmas morning, and not drink any eggnog or eat any latkes.

I am a firm believer that high quality information should be empowering, and knowing about this stuff may be enough to Hawthorne effect yourself.

Don’t turn every day between Thanksgiving and New Years into a license to drink too much and eat huge plates of leftovers.

Celebrate the holidays well, but don’t celebrate every day during the month of December.

We’ll be back next week with a look at how my 2022 predictions fared as we head towards the end of the year.

And, in case you’re wondering, here are my old posts on holiday heart: