How much Afib means you have Afib?

One of the hardest questions in medicine to answer is what we should do about an incidentally found medical problem.

By incidentally found, I mean something that comes up when you’re not looking for it.

Patients with these unexpected findings - medical term: incidentaloma - don’t have any symptoms, but they get told that they have a new medical problem, often one that has the potential for serious consequences.

I see this in a number of different areas on a daily basis but there are two scenarios that are the most common in my daily practice.

Someone has a chest CT scan done as part of lung cancer screening (a controversial topic itself!) and it’s found that they have calcium buildup in their coronary arteries… now they get alarmed with a diagnosis of heart disease!

A fitness tracker or a blood pressure cuff detects an irregular heartbeat and tells them that they may have atrial fibrillation (afib)… now they get turned into someone who is terrified they will have a stroke.

What should we do with these incidental findings?

When should you turn a person into a patient?

A new study called NOAH-AFNET 6 provides some new insight into incidentally discovered atrial fibrillation.

Atrial fibrillation is very common and can be a really big deal

Afib is one of the most common irregular heartbeats that cardiologists see.

I always tell my patients that Afib matters for 2 major reasons:*

It increases your risk of stroke

It can make you feel unwell

When Afib is incidentally detected, the second problem isn’t an issue. You almost certainly can’t feel unwell from something that you didn’t feel in the first place.

There’s the possibility of the nocebo effect here - maybe once you’re told you have Afib, you will feel palpitations and flutters that you never did before - but this discussion presumes that there were no symptoms to prompt testing.

As I wrote about in my newsletter on wearables, the idea that you can prevent strokes by incidentally discovering atrial fibrillation and then putting people on blood thinners is far from proven.

It’s a really important question to answer - should asymptomatic afib that’s incidentally detected be treated the same way as afib that is detected due to symptoms of palpitations or shortness of breath?

How much Afib do you need to have before you have Afib?

This is really the crux of the matter.

I think that almost every doctor would agree that if you are in afib for a week, you probably have afib and should be treated, even if you pop out of it without medical intervention.

And almost every doctor would agree that if you have afib for 3 seconds, you probably don’t need to be worried about it and treating it probably isn’t right.

But where does that cutoff between afib and not-afib live?

The Heart Rhythm Society uses an arbitrary 30 second period to define afib.

Expert consensus like the HRS cutoff is the stuff that a lot of our guidelines are based on, but when there isn’t a huge body of high quality clinical data about a specific question, the medical guidelines are essentially built on a house of cards.

That’s where this new trial comes in and helps shed light on this important question.

The NOAH AFNET 6 trial had a really interesting design

This trial looked at patients who had implanted cardiac devices - pacemakers, defibrillators, cardiac resynchronization devices, and implantable loop recorders - who had irregular heartbeats detected by their implanted device.

They took patients who had “atrial high rate episodes” (AHREs), which are essentially the same as short period of afib.

The investigators randomized patients who had AHREs lasting for at least 6 minutes (6 minutes!) to either anticoagulant therapy or a placebo.

This is a fascinating amount of time to look at, because almost every single cardiologist I know would probably say that 6 minutes of an AHRE means you should be on a blood thinner.**

I’m really impressed that they had the courage to ask this question and to do this trial.

The results of the trial surprised me

The NOAH AFNET 6 trial was actually stopped early because of safety concerns - preliminary data suggested that putting these patients on blood thinners was causing net harm.

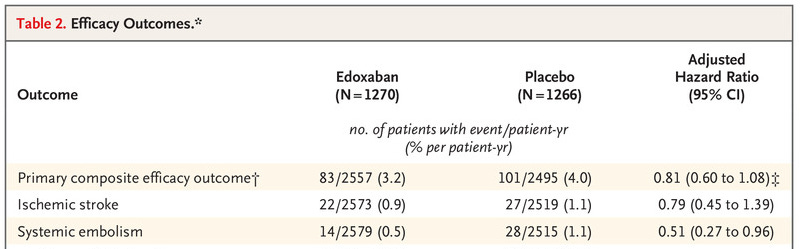

They looked at an efficacy outcome (how well do blood thinners reduce the risk of stroke, embolic event, or cardiac death?) and a safety outcome (how often to blood thinners cause major bleeding or death?) to measure impact on these patients.

Keep in mind that the group of patients here is much sicker than your average Apple Watch wearing population:

Average age of 77, a little more than a third female

More than 25% had heart failure

Over 85% with high blood pressure and more than half on statins

More than 25% had a prior heart attack or stroke

There was no reduction in stroke with anticoagulation versus placebo:

There was a concern in safety outcomes, which was driven by an increase in bleeding complications (not surprising, since these are blood thinners):

The absolute risk of a bleeding complication or death was quite a bit higher than the absolute risk of a stroke in this study.

If you want to get into the weeds a bit more, you can see that there is a suggestion that being on a blood thinner does reduce blood clots. The combination of stroke and embolism wasn’t significant, but embolism alone was:

Going into the trial, I would have expected this trial to be largely positive in favor of anticoagulating these patients.

But that expectation was wrong, and that’s why you do a study like this.

There are a few conclusions we can draw from this trial

This is an important trial that’s going to change my clinical practice.

A few things I will take away from this:

Incidentally found afib that is short and self limited probably shouldn’t be treated the same as regular afib.

Patients with short, self limited episodes of afib have a low risk of stroke. Based on validated risk calculators, you would have predicted that these patients would have a stroke risk around 4% annually, but in NOAH, they had a stroke risk of 1.1% over a period of 21 months

Blood thinners are not without harm, and that’s particularly important to keep in mind as patients age (average age 77 in this trial) when we are making decisions on the margins

I don’t think it’s reasonable to extrapolate these trial results to patients with longer periods of afib or who are symptomatic from their irregular heartbeats.

But this study will also change how I counsel my patients with surprising Apple Watch (or other wearable) readings when they are asymptomatic.

I plan to be much more reassuring in those cases. After all, if a fairly high risk group doesn’t have a net benefit (and appears to have a net harm) from treating asymptomatic, short lived afib, a lower risk group is very unlikely to see much benefit.

And we can also feel confident that the risk of stroke in these situations is really low - so reassurance rather than medicalization may be the better approach.

*The third major reason that Afib can cause medical issues is because of long term adverse cardiac remodeling - being in this irregular heartbeat for a long time can cause the heard muscle to change in pathologic ways. This can cause heart failure and severe valve disease, but I’m this is a complicated and nuanced discussion that’s not pertinent to the conversation at hand.

**AHREs of this length of time are common, occurring between 10-30% of the time when someone has a device implanted.