I'm on team Ozempic

If you talk to someone on the cutting edge in medicine, they’re going to tell you that artificial intelligence is the hottest thing in healthcare right now.

ChatGPT can solve hard medical cases, AI is becoming part of how we train residents, and the New England Journal of Medicine is developing a new AI in medicine journal.

But I am becoming increasingly convinced that when we look back on the 2020s in the future, the most important medical story isn’t going to be how AI took over healthcare, it’s going to be how GLP-1 and GIP agonists changed the way we treat obesity.

The history of obesity treatments is a history of failed medications, ineffective diets, and unsustainable lifestyle changes

I’m not going to bore you with a long history of failed pharmacologic treatment of obesity.

But suffice it to say, if there was a safe and effective weight loss drug before the last few years, it would be making billions of dollars a year and you’d have heard a lot about it.

So unless you travel in medical weight loss circles, you probably don’t know about orlistat, phentermine, or topiramate.

And unless you travel in longevity circles or have diabetes, you probably don’t know about metformin.

The Forks Over Knives and Food as Medicine people get press and attention, but the vast majority of my patients don’t stick with “lifestyle changes” for very long.

Diet and exercise are ineffective as long term treatments for that exact reason - because they don’t stick.

A lifestyle change only makes a difference if it’s a permanent one, and the concept of a diet implies a temporary intervention that you’ll eventually stop and go back to whatever you were doing before.

But along came a class of drugs that target a bunch of hormones involved in something called the incretin effect and suddenly the world of weight loss is dramatically different than it used to be.

This matters because obesity is a major problem and it’s only getting worse

Have you ever seen the CDC heatmaps on obesity? They’re kind of tragic to look at, especially how they have changed over time.

In the leanest states, 25% of the population is dealing with obesity and in the fattest states, almost half the population qualifies as obese.

And so with obesity numbers growing, I think there’s an important distinction to make about whose fault this is.

It’s very easy to blame an individual person for being overweight or obese, but I think that making this entirely about individual responsibility misses the point.

When something changes across a population level like this has, the only explanation is an environmental change.

People didn’t suddenly become lazier or more gluttonous. The environment changed, and our weight changed along with it.

Obesity as an environmental disease is the right framework

Thinking about obesity as an environmental disease rather than an individual one helps a lot when you think about how to treat it.

And I do believe that obesity should be treated.

I think that the Health at Every Size movement is a dangerous message to send to young people because my read of the data are pretty clear - obesity increases the risk of every bad health outcome you can think of.

There’s a difference between blaming or fat-shaming an individual (and fat bias in medicine is real and it’s problematic) and ignoring an issue that worsens someone’s long term health outlook.

So now let’s talk about the drugs that work on the incretin system and just how fantastic they are.

No matter which drug you look at - Ozempic, Mounjaro, Wegovy, or the upcoming Retatrutide - the results are so extraordinary that they’re almost unbelievable

I’m not exaggerating.

What metric do you care about? Because these drugs seem to improve almost everything.

Blood pressure. Body weight. Heart attacks. Major adverse cardiovascular events.

The latest news from Novo Nordisk on the top line results of the SELECT trial studying Wegovy (which is the same thing as Ozempic, Rybelsus, or semaglutide) is just the latest piece of data that fits with all the other pieces of data we have on these medications.

The consensus about how these drugs work is that they act centrally - meaning in the brain - to reduce our appetite.

And that fits with what my patients say - these drugs take the edge of their hunger, and that helps them navigate an environment that’s basically engineered to make them fat and sick.

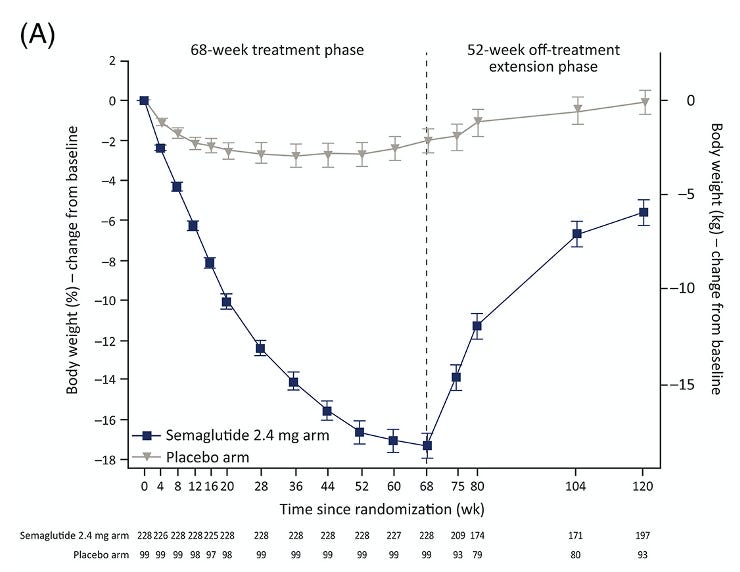

If you look at the studies on these drugs, the curves all look the same

The weight loss curves for all of the drugs in this class look the same. Here’s a sample from the SURMOUNT trial on tirzepatide (Mounjaro):

Rapid weight loss that plateaus after around a year but seems to hold for a while.

And the withdrawal studies suggest that the weight comes back after you take the drugs away (which should elicit a “duh!” from anyone who read the beginning of this article):

Weight loss is most rapid right after starting the drug, and weight gain is most rapid right after stopping the drug.

We don’t have longer term data here, so we don’t know that much about how weight changes after being on these drugs for more than just a couple of years.

We also don’t know about safety data over the long haul, which is vital to understand when you contemplate the risk/benefit analysis for a chronic disease like obesity.

And to be totally fair, this is a very important limitation in starting these on everyone, and a major reason why I am concerned about starting millions of adolescents on these medications.

The concern about muscle loss doesn’t apply for most people

Some of the backlash against these drugs has to do with concern that they make you lose muscle along with fat, making you “fatter” even if your weight is lower.

I don’t think this holds up from the data that we have - the evidence suggests that when properly prescribed, these drugs help people lose way more fat than muscle, which fits with the positive health outcomes that we see in the clinical trials.

The people who are most at risk for losing too much muscle are the ones with little fat to lose.

If your doctor prescribes you Ozempic to lose 10 pounds before you go to Hawaii, you should strongly question whether that doctor has really weighed the risks and benefits of the situation.

And so while there are certainly a lot of long term questions about the durability of weight loss and safety, the data that we have thus far is really exciting.

It’s fair to be cynical about the conclusion that these drugs are going to be everywhere soon

It’s pretty depressing to think that we’re going to spend $1000 per month indefinitely on drugs to treat obesity for tens of millions of people.

And the failure of lifestyle changes across the population certainly makes me feel sad.

The lack of interest and engagement that many of my patients have in exercising more or eating better is one of the things that makes me most cynical in medicine.

The more I think about it, the more persuaded I am that those emotions shouldn’t cloud how we consider a major public health threat.

Anyone who has been to a grocery store recently viscerally understands how difficult it is to navigate the modern environment in a healthy way.

If these drugs can be helpful for millions, and I think that they can, then there are a lot of hard financial and policy questions to answer.

But when it comes to effectiveness on weight loss and improving disease outcomes, the data tell a very consistent story.