Should you be on mushrooms?

Mushrooms are having a bit of a moment in medicine right now.

I had a patient recently who told me that the only thing that has improved her interstitial lung disease related to World Trade Center exposure was turkey tail mushroom.

I’ve had a 4 patients over the last month ask about the benefits of psychedelic mushrooms for treatment of psychiatric disease.

And I’ve weirdly even had multiple friends asking about Lion’s Mane mushroom for cognitive enhancement.

So I decided to take a deeper look at mushrooms for today’s newsletter - both to investigate their medicinal properties as well as to use them as a lens to develop an intellectual framework around supplements we might be considering.

It makes sense to me that mushrooms could be medicine

Many of the best drugs in the world were originally discovered from natural sources.

Some of my favorite examples (not exhaustive by any stretch):

Penicillin - comes from a fungus

Statins - isolated from a fungus during an attempt to discover more antibiotics

SGLT2 inhibitors - originally discovered as a component of the root bark of the apple tree

Aspirin - comes from willow bark

Bioactive compounds are present across the natural world, and people have been using plants and mushrooms (which are fungi) as medicines for thousands of years.

So I completely accept the premise that ingredients found in mushrooms can have a medical purpose.

But is the marketing of mushrooms appropriate given the level of evidence to support their use?

What does the evidence say about mushrooms as medicine?

Let’s take a brief look at a couple of different mushrooms and their active compounds.

We’ll start with the one that’s gotten the most attention: psilocybin.

Psilocybin

This is the active ingredient in psychedelic mushrooms, and you’re going to be hearing more and more about it.

The psychedelic revolution in psychiatry is coming.

There’s decent evidence that psilocybin (the active ingredient in “magic” mushrooms) can effectively treat depression and alcohol use disorder.

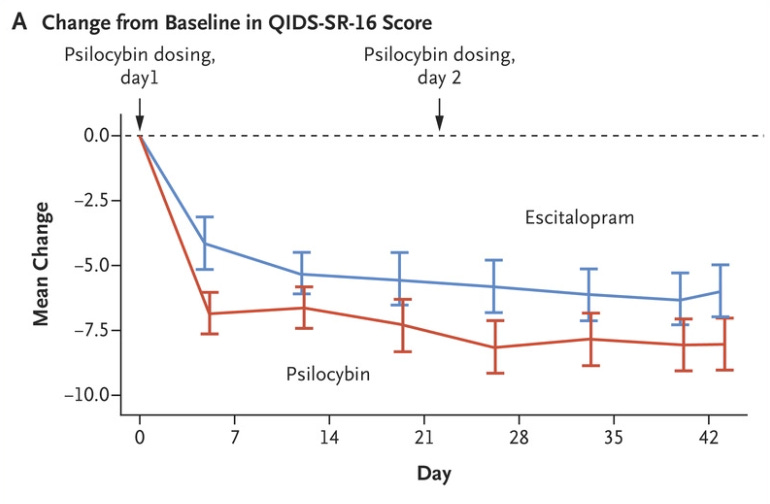

And it’s worth taking a look at the psilocybin for depression trial in detail, because it’s pretty astounding to see the results.

The researchers compared 2 doses of psilocybin given 3 weeks apart to 6 weeks of Lexapro therapy. At worst, psilocybin was equivalent to Lexapro (and possibly even better):

Now, caveats abound - this was a 6 week trial, you shouldn’t see improvement so quickly with Lexapro (raising concern about placebo effect), and we know nothing about the durability of response.

But it’s compelling to think about the long lasting impact of psychedelic experiences on depression and whether that may decrease the need for antidepressants over the long term (and that doesn’t even get into all the doubts about the data to support antidepressants).

Lion’s Mane mushroom

Lion’s Mane mushroom is often marketed as an aid for cognitive function.

It’s a good name for a mushroom that really does look like a Lion’s Mane:

There’s certainly the suggestion from the evidence that Lion’s Mane mushroom may have some positive cognitive impacts:

This study showed a small improvement in cognitive decline for elderly folks during the duration of time they were supplementing with Lion’s Mane.

This one showed a small reduction in depression and anxiety for patients supplementing with Lion’s Mane

Lots of caveats here - short term studies, soft outcomes measured, no real data in healthy people taking it.

Reishi

This mushroom has been a part of Chinese medicine for centuries.

It’s generally used as an anti-inflammatory, and there’s data in a number of different populations:

A reduction in fatigue for breast cancer patients

Improvement in kidney function in patients with a type of kidney disease called FSGS

Increase in some markers of immune system function in patients with advanced stage cancer

Just as with Lion’s Mane, a bit of data doesn’t actually provide any definitive evidence of benefit.

Short term studies looking at biomarkers or subjective measurements in pretty sick patients can’t just be blindly extrapolated to suggest a benefit in everyone.

Cordyceps

Cordyceps mushroom has been used in Chinese medicine to treat fatigue, respiratory and kidney diseases, renal dysfunction, and cardiac dysfunction.

You may know it by it’s other name: Himalayan Viagra.

Cordyceps has been used by as an aid to improve sexual performance among some groups in Nepal and Tibet, who observed that Cordyceps tends to make yaks, goat, and sheep very strong and virile.

It may improve athletic performance in young people and older folks, too.

There’s even data that it improves lipid panels in some animal models.

But large scale or long term human studies are lacking here.

Chaga

Chaga grows in cold climates - Russia, Siberia, Korea, Canada, Alaska.

It’s often used to help immune system function and improve blood sugar and cholesterol levels.

But the data to support use in humans is scant.

It works in test tubes and mice, however.

Turkey tail

Another really well named mushroom:

Turkey tail mushroom contains two substances, polysaccharide peptide and polysaccharide krestin, which inhibit the growth of cancer cells and have antioxidant properties, at least in test tubes.

This is the same story you’ve heard over and over again in this newsletter - a potential biologic mechanism, short term evidence, and limited generalizability or conclusions to be drawn.

The two points I’d emphasize here: the evidence isn’t strong and there are a lot of unknowns

There’s certainly enough preliminary data to suggest that there are a number of mushrooms that might be helpful to some people under the right circumstances.

Unfortunately, we simply don’t have the data to do anything other than extrapolate.

I think that most mushroom supplements you buy - or most psychedelics that you obtain through other means - are probably safe and probably have the benefits you would expect based on all of this preliminary data.

But probably isn’t definitely.

It’s clear from the basic science that compounds present in Lion’s Mane mushroom have potential benefit against cognitive decline.

But what isn’t clear is how to extrapolate that research to conclude anything about whether people without cognitive decline will have an improvement in their normal brain function.

Here’s a non-exhaustive list of questions that arise, even if you generously assume that none of the preliminary research will prove to be inaccurate or not replicated:

Who are the people that benefit?

How long do you need to dose for?

Does the benefit go away if you stop taking it?

What dose maximizes effectiveness?

What dose causes toxicity?

What’s the durability of the treatment effect?

What are the potential side effects?

How big is the effect size? In other words, how much does it help?

Do you need to treat 5 people to prevent a case of cognitive decline/depression/fatigue? Or is that number closer to 500, or even 5000?

And you can’t forget about the elephant in the supplement room: quality control

Our discussion so far hasn’t even touched on my biggest issue with mushroom supplements (and supplements in general): you don’t really know what you’re getting.

Supplements are mislabeled frequently, and I have questions about purity, potency, dose, and a million other factors.

The biggest challenge with taking a mushroom extract as a supplement is less about the biologic plausibility or mechanism and more about the dose, potency, and toxicity.

Are all Lion’s Mane mushrooms harvested across the world throughout the year equal in the amount of bioactive substances? And if they’re not, then how do you ensure that you’re getting the same dose each time to avoid ineffectiveness and toxicity?

Which brings us to a framework to think about supplements or drugs

Most people take medicines or supplements to either 1) fix a problem that exists, 2) prevent a problem from happening, or 3) to enhance normal function.

So any intervention I recommend will have one of those 3 goals, but also have a method of measuring the impact.

When your outcome is nebulous, any effect from an intervention is prone to the placebo/nocebo effect, bias, confounding, and misinterpretation.

I have a hard time recommending my patients use an intervention without a real way to track it’s impact:

If I put a patient on a medicine that lowers blood pressure, we track blood pressure

If I’m treating a patient with shortness of breath related to heart failure, we track exercise capacity and functional status

If I’m treating an irregular heartbeat, we monitor the heart’s electrical rhythm

But the point is that without tracking something, you don’t know how good a job you’re actually doing.

That’s a big challenge with mushrooms and many other supplements - we often don’t have a biomarker and we don’t have an objective metric to track. And if you aren’t tracking anything, how can you be sure it isn’t a total waste of money?

So I’ll leave you with the 5 areas I consider when deciding whether to start and whether to continue any medical intervention:

What am I treating/preventing/enhancing?

What benefit can I expect if I intervene - is the goal to feel better or live longer? And on what time course should we expect results?

How confident am I that the intervention I’m thinking of will be successful? How strong is the evidence?

What are the known side effects from this intervention? How will I monitor for toxicity or intolerance?

What do I track to measure effectiveness?

Overall, when it comes to mushrooms, I think the evidence is pretty good and getting stronger for psilocybin. Unfortunately it’s a bit lacking for the other mushrooms.

But that doesn’t mean there’s nothing there. After all, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.

If you’re enjoying my newsletter, please forward this to one person you know who doesn’t read it and encourage them to subscribe!