Thanksgiving Mailbag

Happy Thanksgiving!

I will spend this Thanksgiving thankful for many things. But I wanted to express my gratitude to all of the readers of this newsletter. Thank you for reading my words and for sharing them - it remains a lot of fun for me, particularly the exchange of ideas with you all.

I really enjoyed receiving the questions you sent in - thank you all for sending. If this mailg is well received, we’ll do another one again soon.

Let’s get into the questions.

How does the training that doctors receive lead many doctors to be very poor motivators, and poor at inciting lifestyle change in their patients? What options for ROI, can be shown in soft skills, for doctors to become (or add an additional process) to motivate and hold accountable patients for lifestyle change?

While there’s an argument to be made that the most effective doctors are great coaches, motivators, and ultimately, salespeople to persuade patients to take control of their own health, it’s certainly not an opinion that everyone shares.

Physicians have specialized training to make decisions about medical treatments that lifestyle coaches, nutritionists, and personal trainers don’t have.

We have the ability to prescribe medications that have significant side effects and to send patients for invasive treatments that have significant risks to them.

There’s a phrase that’s sometimes thrown about called “practicing at the top of your license,” which further emphasizes this point - even though a doctor can do the motivating and lifestyle coaching, maybe that’s not what we should be doing.

But I think that part of the debate is a bit too idealistic to accurately explain the world that we see.

In this case, the cynical explanation is probably the right one: I don’t get paid any differently if I persuade my patients to exercise more, eat better, and manage stress in a way that improves their health and reduces their medical needs.

In fact, I probably get paid less because that means I’ll see fewer patients.

The health care system incentivizes numbers, and so for many doctors, it’s a no-brainer to just throw a prescription or a procedure at whatever problem is at hand.

It’s faster and less cognitively challenging to just prescribe a blood pressure medicine than discuss the non-pharmacologic treatments for hypertension. And it’s more lucrative to do so.

I think the training that we get is barely an issue here.

Do you recommend Ivermectin as a prophylactic and as a treatment for Covid?

2019-me would have been incredulous that in 2022, you could predict with a high level of confidence how someone voted based on their opinion of ivermectin.

But Covid has been a weird time, and here we are.

The ivermectin story is sort of interesting - repurposing a drug that has a long track record of safety because in vitro activity and preliminary data suggested a benefit in Covid makes sense, and I think that thoroughly investigating the promise here is the right thing to do.

But when you dig into the data - and I mean really dig into the data - you see that ivermectin probably isn’t a wonder drug for Covid.

The two highest quality trials here both showed a neutral effect.

And so even though the data that we have doesn’t rule out the possibility that ivermectin may have some benefit here, the sum total of the information says to me that there probably isn’t much benefit here.

Anyone selling you ivermectin is probably trying to take advantage of you.

In 2022, for someone who has been vaccinated and doesn’t have a suppressed immune system, Covid is almost certainly going to be a mild, self limited disease.

I tend to think that most of the people pushing panacea treatments for Covid are just doing it because they’re going to make money off of it.

Speaking of making money off of Covid…

Do you recommend Paxlovid as a treatment for Covid?

Paxlovid began 2022 looking like a wonder drug, when the EPIC-HR trial showed an 89% reduction in death or hospitalization in folks randomized to Paxlovid.

And when it first came out, my biggest concern was that it was going to be too expensive and too unavailable to make a different for most of us.

I hadn’t realized how giving billions of dollars to Pfizer with guaranteed purchases was going to make the drug widely available and easily accessible.

At this point, Pfizer stands to make over $20 billion from Paxlovid.

And unfortunately, the more we learn about the drug, the less beneficial it seems.

To start, the EPIC-HR trial wasn’t conducted in patients who had been vaccinated, and there’s no plan for a randomized trial of the drug in vaccinated patients.

Next, the data really suggest that there’s no benefit in low risk patients. The argument to give Paxlovid to anyone under 65 is really lacking.

My clinical experience with the drug hasn’t been great, to put it mildly. Most of my patients get rebound infections and end up sicker for longer than they would have been if they had just gotten through the infection.

The drug-drug interactions here are no joke. Especially for patients who need to be on blood thinners that interact with Paxlovid and need to be briefly stopped, you need to make sure that the benefit is really greater than the risk.

And finally, Covid is a different disease now than it used to be. The virus has mutated, the population has more immunity, and while the widespread prescribing of Paxlovid may have made sense in a different time, now it should really be reserved for the highest risk patients.

It is my impression that more and more, patients are having serious surgery in a hospital and then being sent home to have their friends and family help with the aftermath. The hospital gives a rapid briefing to the person who will be doing the caregiving, hands them printed instructions, and off they go. I was the caregiver for my son when he had shoulder surgery for a rotator cuff tear. It was all new to me, and I wondered constantly if I was doing the right thing. I find the same situation as I approach a hip replacement. Under Medicare, I get one night in the hospital, and no stay in a rehab facility. These are changes in support for the patient's recovery. These changes seem unwise to me, and I'd like to hear you discuss this situation.

This set of circumstances is totally unsurprising for anyone who works in a hospital.

It all comes down to money.

Hospitals operate on tiny margins. Shorter hospital stays mean more patients and thus higher reimbursement. When hospitals are penalized even small percentages of revenue, it can change behavior in significant ways.

Some of the major metrics that hospitals get judged on are length of stay and time of discharge, particularly discharges before noon.

When I get shown the data on how I’m doing taking care of patients in the hospital, I don’t get shown information about my patient outcomes or my treatment decisions.

They show me metrics regarding how I do at discharging patients: my length of stay and my discharge before noon percentage.

And when my numbers aren’t up to par, it leads to a series of conversations reminiscent of a discussion about TPS reports.

Unfortunately, as mentioned in the question, the metric-ization of health care isn’t just something that I get annoyed by, it also leads to bad things happening to patients.

This is partly a problem of the myth of “paying for quality” in healthcare. Because quality is so hard to measure, we end up applying Goodhart’s Law to the healthcare system with a lot of unfortunate unintended consequences.

It’s a major problem, and I have no clue how to improve the system.

As a meditation and mindfulness practitioner, these are special gifts, that enhance our health and well-being. They help us be truly alive, reveal our character, and appreciate each moment. As you know there is supportive evidence to consider and evaluate. I would love to get your analysis and recommendations.

There are very few things in medicine that are less well understood than the mind-body connection.

I think about the subconscious impact here through the lens of the placebo effect, but I think this question is more about the conscious way that we guide our mind to heal our bodies.

I am a firm believer that the mind-body connection is very real, but it’s unfortunately almost impossible to quantify and even more difficult to measure.

I don’t have much wisdom about how to get started here, but I’m fully persuaded that this is an area of great importance and impact on health.

I was wondering if you recommend CoQ10 for people taking statins.

Muscle pain from statin use is the most common side effect of these drugs and the most common reason that people in my practice discontinue them.

Unfortunately, people who suffer from statin-induced myalgias tend to have worse cardiovascular outcomes than people who don’t. This is probably because it means they’re less likely to get lipid lowering therapy.

Fortunately, only about 5% of people who take statins develop these muscle aches. The vast majority of patients on statins take them and feel exactly the same as before.

For a subset of the patients who develop statin-induced muscle pain, coenzyme Q10 might be beneficial.

I don’t think there’s much risk in taking CoQ10 if you know that’s what you’re getting.

The risk here is more a general risk you take with any supplement - the uncertainty about quality control, purity, and whether what’s in the bottle matches what’s on the label.

If you get muscle aches from a statin, CoQ10 is totally reasonable to try.

Most of the time, these muscle aches are able to be treated through changing the medication, frequency, or dose.

And, essentially 100% of the time, the muscle pains go away in a couple of weeks after stopping the medicine.

Do you have advice about how to find a well trained cardiologist for an emergency in a foreign country? Sometimes the American embassy/consulate has a list of English speaking MDs but that doesn’t say much.

I would be less concerned about finding an English speaking doctor than in finding a hospital that has experience in taking care of really sick patients.

Presumably, if you’re looking for a physician in a foreign country, it’s because you’re really sick and something bad happened.

In these cases, you’re usually going to be better served in a big hospital that has a lot of capability with an average doctor than you are with the best doctor in the world in a hospital that doesn’t have the tools available to treat someone very sick.

Medical training across the world is pretty fantastic - the United States doesn’t have a monopoly on training high quality physicians (although US physicians do have a monopoly on providing medical care in the US, which keeps physician salaries much higher than they would be otherwise).

So much of practicing medicine well is about interpreting objective data that crosses language barrier - an EKG in Spanish is the same as an EKG in English - and in an emergency, doctors generally need to know much less about the details of your symptoms than they do about your vital signs, bloodwork, and the medications you take.

Whenever you’re traveling (domestically or abroad), I recommend having an easily accessible document (either digital or printed) with your medical history and medications that can be shown to a physician in an emergency.

How would you counsel a patient who has a single, self-resolving episode of atrial fibrillation? Does that person still have a fib, or did is it something you have forever?

This is a really hard question to answer.

Once you’ve had atrial fibrillation, it suggests you have a “ticklish” heart (for lack of a better word), that, under the right circumstances, develops a dangerous irregular heartbeat.

How to approach this depends on a handful of individual factors - age, other medical conditions, symptoms when the arrhythmia developed, alcohol use, sleep apnea, family history - and so there’s no one-size-fits-all answer here.

As with many things, this type of care should be really tailored to the individual in question.

I hesitate to give the generic advice of “talk to your doctor about it,” but in this case, that’s absolutely the right answer.

When is the best time to take blood pressure meds, at night or in the morning?

The best time to take medications is when you can consistently take them.

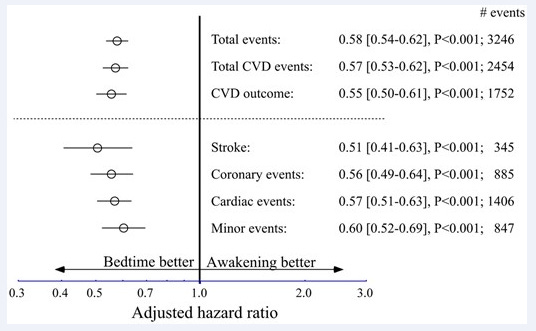

There’s at least one randomized trial looking at this question, which found a surprisingly large benefit in taking BP meds at night versus in the morning:

The effect size here is so large that I am a bit skeptical it would hold up - I find a 50% reduction in stroke based on time of day for BP meds implausible. And while the data are what the data are, this is the type of result I’d like to see replicated before I am fully persuaded.

That said, it’s more important to take medications consistently than to try to optimize the exact right time to take them.

And so if someone prefers to take medications in the morning, or finds it easier to do so, I think that it’s totally reasonable to do so.

Thank you all for reading and sharing my newsletter!

I hope you all have a wonderful holiday!

Back next week with more.