The biggest waste of time in medicine

We do a lot of dumb things in medicine.

We still use fax machines. We make thousands of clicks in the electronic medical record everyday. We put people on unnecessary medications and we do unnecessary procedures.

But I think that the dumbest thing that we do is “clear” people for surgery.

Pre-surgical “clearance” is a huge part of medicine. I’ve seen dozens of these cases in the past few weeks. In just the past 3 days, I’ve seen patients for pre-surgical clearance before a cataract operation, a cosmetic facial plastic surgery procedure, and arthroscopic knee surgery.

For most people, the pre-op process is a waste of time and money. It causes stress and doesn’t lead to better care.

If you’ve ever gone for a surgery, you probably had to do some variation of a pre-surgical scavenger hunt: get medical clearance, a chest X-ray, bloodwork, an echocardiogram, a stress test, and then cardiac clearance.

It’s pretty damn annoying!

But surely there must be strong evidence that pre-op testing saves lives. Otherwise we wouldn’t do it, would we?

What’s the point of a pre-surgical medical evaluation?

A lot of surgery happens each year - more than 25 million people undergo non-cardiac surgery annually in the US.

A non trivial number of these patients - between 1-5% - have a heart attack or stroke in the period around their operation.

These peri-operative cardiovascular issues cause major problems like bad patient outcomes, prolonged hospital stays, and they cost about $20 billion a year.

So anything that we can do to prevent these problems with our pre-op testing would be great.

Unfortunately, most of the things that we do for patients before surgery are either pointless or harmful.

The cautionary history of beta blockers to reduce surgical risk

If you go back to the early 2000s, prescribing a beta blocker before a patient went for surgery was the standard of care.

The thinking went that beta blockers before surgery would reduce risk of heart attacks because they lower heart rate, blood pressure, and shear stress on the arteries.

And that’s exactly what the DECREASE trials showed: giving beta blockers before surgery reduced the risk of heart attacks by about 80%.

Unfortunately, there were two problems here:

The principal investigator of the DECREASE trials, Don Poldermans, perpetuated a huge fraud. He fabricated data, didn’t consent patients to participate in the trials, and knew that his data was garbage when he submitted for publication.

The quality of the study was crappy to begin with, so it never should have changed clinical practice without a confirmatory trial.

I won’t belabor the first problem. Fraud is bad, and I am against it.

But the second problem here is emblematic of perhaps the worst part of medicine - when mediocre data leads to broad practice change before higher quality data refutes the findings.

This practice is known as medical reversal, and every single instance of it is a systemic failure.

While some people recognized at the time of DECREASE that the data were too good to be true and that we should be skeptical without confirmation, a beta blocker before surgery was part of clinical practice guidelines and led to the incorrect treatment of many thousands of patients.

It wasn’t until years later that the POISE trial showed us that, while beta blockers do reduce heart attacks when given before surgery, they also cause more patients to die and lead to more strokes.

But preop evaluation isn’t just about giving medications - we also send patients for lots of tests

I see patients going for surgery all the time who bring in a form asking me to send the surgeon results from their echocardiogram and stress test.

It shouldn’t be surprising that people with an abnormal echocardiogram or an abnormal stress test have worse outcomes when they go for surgery.

But how do we decide who needs these tests before surgery?

The American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association Guidelines recommend evaluating a patient’s cardiovascular risk with a method called the Revised Cardiac Risk Index, or RCRI score, and then assessing their functional capacity.

If you have elevated risk according to your RCRI score, and you are not able to walk up 2 flights of stairs, then most doctors end up sending you for a nuclear stress test and an echocardiogram.

There’s pretty good evidence that a poor functional status means a higher risk of heart attack related to surgery.

But there is zero data - ZERO! - to support the idea that testing people beforehand does anything to change their surgical risk.

Acting on an abnormal stress test before surgery doesn’t reduce cardiac risk, so why get one in the first place?

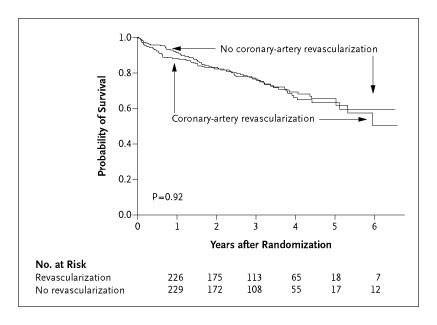

We know this from a study called the CARP trial.

CARP looked at patients going for open vascular surgery - the highest risk surgical procedure.

In this trial, they studied patients going for high risk surgery at elevated cardiac risk who had at least one severe blockage in one of their coronary arteries.

The CARP investigators randomized these patients to fixing the blockage with stents or bypass surgery versus simply leaving them alone and doing surgery anyway.

It doesn’t take a fancy statistical analysis of the survival curve to understand the results - there’s no difference in survival between the patients who had their cardiac blockages fixed and the ones who just went to surgery without doing anything:

So if fixing a severe blockages in the highest risk patients (those with severe coronary artery disease) going for the highest risk surgery (vascular surgery) doesn’t save lives or prevent heart attacks, what’s the point to fixing the blockages?

And if there’s no point in fixing the blockages, then what’s the point in looking for them in the first place?

If you’re confused, then that makes two of us.

The CARP trial is the study that turned me into a bit of a pre-op nihilist. If we don’t make a difference in the sickest patients by acting on an abnormal stress test, why would we expect lower risk patients to benefit?

I simply don’t understand the decision to perform routine preoperative stress tests. An abnormal test that leads to a cardiac catheterization and a stent being placed doesn’t reduce the chance that someone has death, heart attack, or stroke related to surgery.

As a result, there’s an underpants gnomes quality to most preop testing:

Stage 1: Do a stress test

Stage 2: ?

Stage 3: Profit

Before you draw universal conclusions, be careful about what I said and what I didn’t say

Now, before you conclude that every single piece of preoperative testing is pointless, keep in mind that there are almost no universal truths in medicine.

Different people are different.

When it comes to preop testing, just because there is a lot of bathwater to throw out doesn’t mean that there aren’t some babies in there.

When I talk about the futility of this process, I’m talking about the majority of patients going for the majority of surgeries.

There are some people I will always hold up before going for surgery:

Patients in acute decompensated heart failure

Patients with unstable chest pain syndromes

Patients with active blood clots

Patients with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis

There are just some of patients who need to have testing done.

But the vast majority of people who go for surgery have their time and money wasted by unnecessary preoperative testing and appointments.

In medicine, we often talk about the concept of sins of omission versus sins of commission

Unnecessary pre-operative testing is a sin of commission - we’re doing something, even if that something is unnecessary and may lead to harm.

These sins of commission are easy to explain - “I wanted to be sure we didn’t miss anything” - and it provides the physician with a way to CYA in our litigious world.

After all, if someone ends up with a heart attack after a hip replacement, it’s easy to blame the doctor who sent them for surgery without doing a stress test first.

But sins of omission aren’t worse, even if they may appear less defensible during a deposition.

I feel pretty confident that the evidence supports a decision not to send someone for a stress test that they don’t need, even if the expectation may be that we do the test.

You may have heard the phrase, “don’t just stand there, do something.”

Well, in the case of routine preoperative testing, I think that we should turn it around: “don’t just do something, stand there.”