In 2006, a group of researchers from UT Southwestern published a paper on a newly discovered genetic variation that seemed to lead to an extremely low lifelong risk of heart disease.

The researchers noted that people who had nonfunctioning variants of a protein called PCSK9 had a modest reduction in LDL cholesterol levels (about 28%) but a whopping 88% reduction in the risk of developing clinical heart disease.

Read that one more time - a genetic variation that leads to a small reduction in LDL cholesterol leads to a massive reduction in lifelong heart disease risk:

We’ll come back to that concept - a small reduction for a long time dramatically lowers lifelong risk - a bit later on.

At the time of this discovery, no one really understood what PCSK9 did, but the observation about its impact was clear: when PCSK9 doesn’t work very well, it leads to a very low lifetime risk of heart disease in otherwise normal people.

The PCSK9 discovery is incredibly important for the way that in informs our understanding of heart disease.

This discovery also happens to be the beginning of a tremendous scientific triumph that you probably haven’t heard about, but you should have.

What the hell is PCSK9?

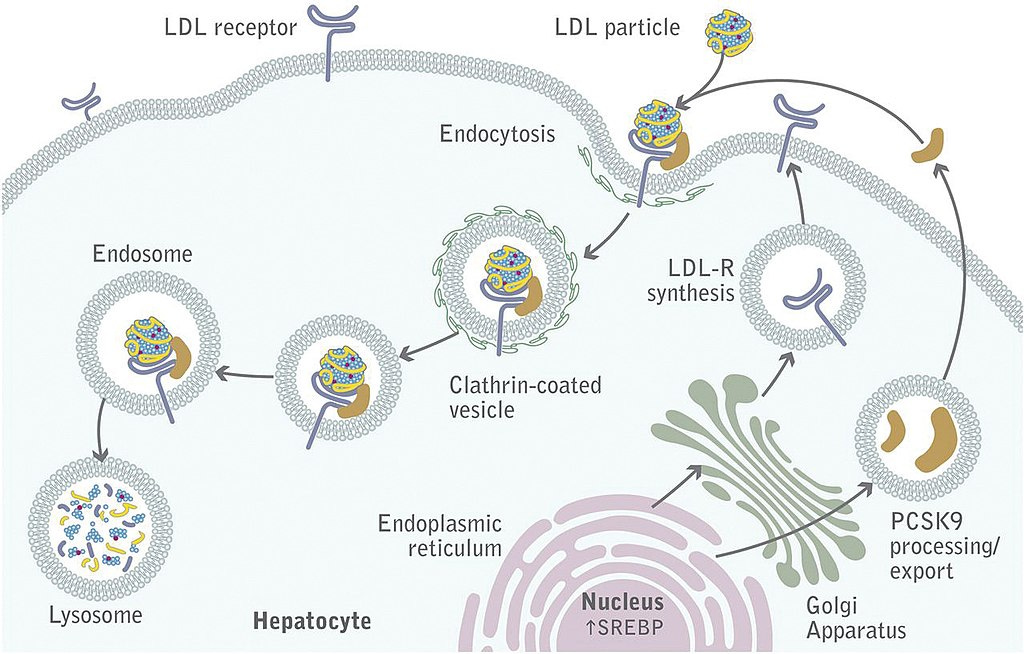

PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 serine protease gene) is a protein that helps to bring LDL receptors off the surface of liver cells.

When the LDL receptor is sitting on the surface of liver cells, it clears LDL particles from circulation and lowers blood levels of LDL cholesterol (and LDL particles).

When PCSK9 is working well, it means that the LDL receptors spend less time taking LDL particles out of our bloodstream, which means our LDL goes up and so does our heart disease risk:

The patients identified in the 2006 paper were born with a genetic variant that led to a loss of function of PCSK9.

Instead of taking the LDL receptors off the surface of liver cells, the malfunctioning PCSK9 left them up, where they could do the work that we want them to do, clearing LDL from circulation and lowering numbers.

The important insight about cardiovascular prevention from these patients: risk = exposure over time

I mentioned above that these patients only have a small reduction in their LDL cholesterol numbers but they have a markedly lower lifetime risk of heart disease than people with more normal levels.

Most experts in heart disease prevention think about cardiac risk as being related to exposure over time. High LDL for a year or two isn’t a huge deal, but high LDL over a few decades has a big impact on risk.

The PCSK9 variant described in the paper leads to a decreased exposure starting from birth - exposure over time is markedly less because it happens over decades, even if the reduction in LDL isn’t very large.

It’s also important to note that there doesn’t appear to be a huge tradeoff here - you don’t lose the function of PCSK9 and get a drop in heart disease risk in exchange for something else bad.

These patients did not have any other signs that a poorly functioning PCSK9 was problematic: they had normal cognitive function, normal lifespan, no signal for increased cancer risk, no change in development, no change in fertility, and otherwise seem to be perfectly healthy.

It’s as close to a free lunch as I’ve seen in biology.

Fast forward 11 years - we have drugs to target PCSK9 that are pretty remarkable

You won’t be surprised that a natural genetic variant that lowers heart disease risk very quickly became a target for drug development.

The pharmaceutical industry took this insight and ran with it extremely quickly and effectively.

By 2017, 11 years after the initial discovery, we had outcomes trials that demonstrated a reduction in heart disease with two different drugs that inhibit the function of PCSK9, alirocumab (Praluent) and Evolocumab (Repatha).

The story from these trials (ODYSEEY OUTCOMES and FOURIER) is pretty clear.

Inhibiting PCSK9 with drugs lowers LDL cholesterol, even in people who are already on statins:

And more importantly, inhibiting PCSK9 with drugs also lowers the risk of heart disease in patients already on statins, and the magnitude of that benefit appears to increase over time:

This is kind of amazing.

In just 11 years, humans have gone from identifying a genetic anomaly to developing drugs that mimic that genetic anomaly, to testing these drugs in Phase 1, 2, and 3 clinical trials and demonstrating them to be safe and effective.

And I think it’s worth pointing out just exactly how incredible the data from those trials is. The patients studied in ODYSSEY and FOURIER had advanced cardiovascular disease and were already pretty well treated medically.

Inhibiting PCSK9 further improves outcomes in just a couple of years of treatment.

The clinical trials are what make the PCSK9 story so incredible

The dramatic PCSK9 success story is interesting to contrast with the CETP story.

CETP is another protein with a genetic variant that’s been found to be associated with long life and freedom from cardiovascular disease.

But when CETP inhibitors have been tested in clinical trials, the outcomes have been either unimpressive or demonstrated harm.

There’s a bit more to the CETP story, and some potentially exciting things on the horizon there, but thus far, the PCSK9 story has been a gigantic success, just like the CETP story has been a gigantic failure.

And that’s what makes PSCK9 so fascinating to me and so worth of celebration.

Every once in a while when I prescribe one of these drugs, I stop to marvel at what an amazing story of human ingenuity it is that these medications exist.

We found a genetic variant that lowers the risk of heart disease and turned it into safe and effective drugs to lower heart disease risk in just a bit over a decade.

It’s pretty remarkable, and it’s a story we should be telling more. There’s a lot to be cynical about in medicine and in science, but the PCSK9 story is the type of work that gives me optimism about the ongoing pursuit of medical advancement.