It was inevitable that there was going to be a backlash against Ozempic and other safe and effective weight loss drugs at some point.

This happens with any public health intervention or medications that eventually develops mass appeal. Just look at statins, fluoride in water, and Covid vaccines. Or just vaccines in general, for that matter.

And so with these drugs showing promising to totally upend the way that we treat obesity and change the trajectory of one of the biggest ongoing public health catastrophes, it shouldn’t be surprising that there’s been a backlash.

When it comes to these weight loss drugs, my impression of the backlash is that it’s fraught with half truths, misleading information, and some fear mongering.

And while there are legitimate reasons to be concerned about the overuse of these drugs, I’m worried we’re going to end up underusing a treatment that can help a lot of people.

Let’s take a look at some of the backlash and provide some perspective.

The pediatric guidelines mean that we’re going to put kids on these drugs forever

The recently released guidelines on the treatment of obesity for children and adolescents from the American Academy of Pediatrics received a lot of media attention, most of it negative, about medicalizing what should be a lifestyle conversation.

The biggest problem with the backlash is that I suspect most people complaining haven’t actually read the guidelines - if you actually read what’s written in them, you’ll find the text to be measured and reasonable:

“Pediatricians and other PHCPs should offer adolescents 12 years and older with obesity weight loss pharmacotherapy, according to medication indications, risks, and benefits, as an adjunct to IHBLT (KAS 12). Pediatricians and other PHCPs should offer referral for adolescents 13 and older with severe obesity for evaluation for metabolic and bariatric surgery to local or regional comprehensive multidisciplinary pediatric metabolic and bariatric surgery centers (KAS 13; see Table 22).”

In other words, think about the risks, benefits, and indications. And think about the medications as an adjunctive therapy to be used in addition to lifestyle changes.

But the backlash has something right - we don’t know what we don’t know here.

While there’s certainly data to suggest short term safety and effectiveness of GLP-1 agonists in an adolescent population, there are a lot of unknowns about the long term impact of being on these medications during times of significant developmental changes.

How do these drugs impact bone density during these years? What about muscle mass development or sex hormone production during puberty?

Since they act on the brain as a means of reducing appetite, how does this change the circuitry of a still-developing brain?

The unknown unknown of giving these drugs to people who may take them for decades would make me pause before prescribing during these formative years.

You have to take it forever or you’ll gain the weight back

Well, duh.

Obesity is an environmental disease. If you don’t permanently change the environment, weight is going to come back on.

I’m sure you’ve heard something along the lines of “no diet works forever.”

Eating less and exercising more often helps people lose weight. But if you stop doing those things, the weight often comes back.

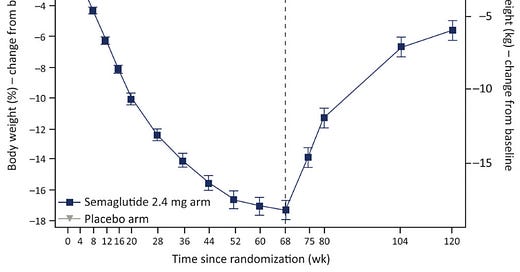

These drugs are the exact same and the data backs it up:

There’s no magic pill that makes us young, healthy, thin, and beautiful forever after a single dose.

If a medication to treat obesity works by spontaneously decreasing appetite to cause weight loss, it should be intuitive that withdrawing that drug is going to increase appetite and lead to weight gain.

Again, obesity is an environmental disease - our bodies don’t work well in the current obesogenic world.

If using one of these drugs becomes a catalyst to permanently change lifestyle habits, then it will lead to permanent weight-loss. If it doesn’t, and nothing changes apart from taking the drug, then stopping it will lead to weight regain.

It’s not clear to me why this would be controversial, confusing, or an argument against these medications.

It causes the weight loss to come from muscle instead of fat and thus you become “fatter” even if you lose weight

There was a minor internet argument after a segment on Megyn Kelly’s Show with Dr. Peter Attia discussing muscle loss that he’s been seeing with his patients on Ozempic:

Some smart commentary reviewing the published data from Dr. Mike Albert persuaded me that the patient population referenced by Attia is likely quite different than the patients that these drugs were studied on.

I can’t embed the Tweet because of the stupid war between Substack and Twitter, but here’s a link to the thread and a screenshot of one of the most persuasive points:

Anything that makes you lose weight will cause you to lose muscle mass. One of the keys with healthy weight loss is to minimize the loss of lean tissue AKA muscle, while maximizing fat loss.

The things that help us maintain muscle mass are adequate protein intake, strength, training, and avoiding rapid and dramatic calorie reduction that makes us drop weight too quickly.

The relative proportion of muscle versus fat that you lose is likely going to be dictated be a few things:

Where you started - how much body fat did you have to lose?

How effective was the drug and how dramatically did your calorie intake change?

Are you getting enough protein on your new diet?

Are you strength training to send your muscle the right signals to maintain itself?

When bodybuilders are cutting before competition, they all lose muscle mass despite the fact that they’re doing everything in their power to maintain every ounce. Regular people are no different, and we would all lose muscle mass on these drugs.

The amount that you lose, and more importantly, whether or not that muscle loss is ultimately harmful to your health, it’s going to depend on where you started and how you mitigate it.

It’s cheating to use a medication like this. We should be promoting diet and exercise instead

I’ve always been naturally thin. I’ve had to expend essentially zero effort my entire life at losing weight. My appetite seems to be naturally regulated.

Now, I’m generally pretty careful about what I eat; I try not to snack, I don’t drink much alcohol, and I don’t eat much dessert. I eat a lot of plain Greek yogurt, berries, spinach, chicken breasts, and sweet potatoes. I also exercise regularly and have the luxury of being able to afford to buy high quality, fresh food whenever I need.

But weight maintenance has always been easy for me. I also know a lot of smart, successful, disciplined people for whom it isn’t easy. I have a hard time thinking that the difference between me and many others is really based on willpower and that genetics don’t play a big role.

It’s conceivable that the difference here is I have naturally higher levels of GLP-1 than someone who has a harder time maintaining their weight.

And so is it possible that taking a drug like Ozempic is actually just leveling the playing field by putting us on equal hormonal footing?

I don’t really know, but I do know that willpower is selective and that there’s a big difference between the hunger that many of us experience.

Eating less junk food and doing more exercise is important. And exercise in particular, seems like it may be a bigger driver of health promotion than any specific dietary change.

You can see these drugs as tools in the treatment of obesity that are complementary rather than competitive with diet and exercise.

That’s how I view them.

The bottom line here: these drugs are effective tools to treat obesity, and they should be used for people who need them

It’s hard for me to imagine that there aren’t cases where the benefit outweighs the risk, but the converse is also true.

There are certainly going to be patients for whom these drugs are recommended, who will have unexpected, or maybe even unforeseeable long-term negative impacts.

We should all be cautious about prescribing drugs that will be used for decades after only being studied for years.

But at the end of the day, a drug that treats weight loss is really not that much different than a drug that does anything else.

If you are able to choose the correct patient population, it’s very likely that the benefit of the drug will outweigh the risks.

If you broadly use these medicines on lots of people who may or may not need it (and who certainly wouldn’t have met the inclusion criteria for the clinical trials), you’re going to end up with side effects, unintended consequences, and lots of situations where the risk is greater than the benefit. i

So giving Ozempic to a bunch of non-diabetic people with 16% body fat and no significant medical problems caused by excess weight with the goal of losing 10 pounds creates a situation without much potential benefit but with some risk.

The less you stand to medically benefit from weight loss, the less likely it is that the risk-benefit equation is in favor of you using drugs to get there.

But if a theoretical concern about loss of muscle mass reduces prescriptions for our patients with 40% body fat, elevated blood sugar, and hypertension, then I’m afraid we’ve just thrown out the baby with the bathwater.

The backlash against statins causes more people to die from heart disease and the backlash against Covid vaccines causes more people to die from Covid.

GLP-1 agonists are tools to treat obesity, and I’m concerned that the backlash against them will lead us to undertreat people who could benefit a lot from these medications.