What is holiday heart syndrome?

Every year around the holidays, there’s a spike in cardiovascular symptoms leading to more doctor’s visits, hospital admissions, and new prescriptions.

This spike in cardiac issues around the holidays was first described in the 1970s, and termed “Holiday Heart Syndrome,” for obvious reasons. Additional research suggests that you have a higher likelihood of dying from a heart attack during the holidays than during the rest of the year.

Each year around this time, a few media organizations will do a segment on holiday heart syndrome with a few pithy recommendations about how to prevent it.

The original articles on Holiday Heart looked at the heart’s electrical system, but the cardiovascular impact of the holidays isn’t just felt with abnormal heartbeats. Let’s take a look at the different manifestations in a bit more detail.

I break these down in my head to the acute manifestations (irregular heart beats and heart attacks) and the chronic manifestations (weight gain and increased risk of chronic medical problems) of the holidays.

Irregular heart beats

Atrial fibrillation (often called Afib) is the most common irregular heartbeat in America. Around 3 million Americans have this abnormal heart rhythm, which increases your risk of stroke and congestive heart failure.

The most common symptoms of Afib are palpitations and shortness of breath. But many people don’t have symptoms at all.

The increased incidence of Afib around the holidays seems to be related primarily to increased alcohol consumption. Alcohol has a number of different biologic effects on the heart, and it’s well described that a single episode of heavy drinking can cause someone to go into atrial fibrillation.

Identifying atrial fibrillation is best done with an electrocardiogram (also known as an EKG or ECG), but there are plenty of home monitors that can help to pick it up, such as the Apple Watch and the AliveCor Kardia Mobile.

The answer for how to prevent Afib around the holidays is obvious - don’t drink heavily. But it’s equally important to go get checked out if you develop new symptoms of palpitations, shortness of breath, or chest discomfort.

The question that naturally arises after this happens: does having a single episode of Afib around the holidays brought on by heavy drinking mean that you “have Afib?”

I don’t think anyone truly knows the answer to this question; in general, I tend to think the answer is yes. Your heart has shown a predisposition to have an irregular heartbeat when given a nudge, so there’s something about your heart’s electrical system that’s a bit ticklish. It wouldn’t necessarily make me treat every patient for chronic Afib, but it does make me consider your cardiovascular physiology a bit differently.

Heart attacks

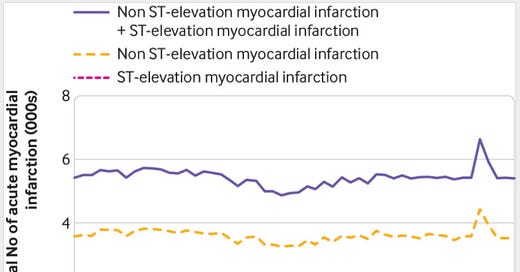

There’s certainly a signal that heart attacks are more likely around the holidays than other times of the year. Take a look at this graph from a British Medical Journal article on calendar timing of different types of heart attacks:

Now, anytime you see an increased incidence of anything medical, you need to ask yourself if there’s truly an underlying change in the disease or if what we’re seeing is just a matter of better detection.

Put more simply: are more heart attacks diagnosed around the holidays because people are with family who make them go to the hospital when they would otherwise ignore their symptoms?

I don’t think that’s the case here, because if this phenomenon were just about better detection, you’d expect a drop in incidence right after the holidays. That’s not what we’re seeing here.

The death numbers bear this increased likelihood of a heart attack out: more people die from heart disease around the holidays than any other time of year, at least partly because more people are having heart attacks:

So what explains more heart attacks around the holidays? A handful of different proposed mechanisms have been thrown around. A few potential culprits:

Emotional stress associated with the holidays

More physical activity in cold weather

Changes in diet and alcohol consumption

Delay in seeking medical care until after the holidays

Anytime you see a handful of different explanations for something, that probably means two things: 1) no one really knows; and 2) whatever you’re looking at is probably multifactorial, meaning there’s more than one contributing factor.

The bottom line: heart attacks occur more frequently during the holidays and people are more likely to die from heart disease during this time. That means you should be prompt in seeking out medical attention if you develop any symptoms of new chest pain, chest pressure, trouble breathing, or generally feeling unwell.

The other big issue with the holidays: weight gain

It’s no secret that many Americans are overweight.

But weight gain doesn’t just happen suddenly. It’s a gradual process taking place over years. And it seems that the insidious weight gain around the holidays plays a really important role here.

According to some research, the average person gains about a pound over the holidays. And folks don’t seem to sustainably lose this weight afterwards.

That may not seem like much, but if it happens every year between ages 20 and 40, all of a sudden you look back and you’ve gained 20 pounds.

I suspect that this slow creep of gradual weight gain is really important for many of us.

Now, I’m not going to lie to you and tell you that gaining one pound is really that big a deal. But just like a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step, the march towards obesity begins with a single pound of weight gain.

This newsletter isn’t the Dr. Oz Show - I’m not going to offer you 10 tips for avoiding holiday weight gain. But information is power and now you’re armed with the knowledge of common holiday weight gain. So you can do something about it.

Happy holidays to all!

Thank you for subscribing! I appreciate you reading. If you’re enjoying my newsletter, please share with friends and family and encourage them to subscribe!

**Important disclaimer: this is not medical advice. Every medical case is different and I would recommend caution in extrapolating anything here to any specific medical case**