Johnson & Johnson just agreed to buy Abiomed, a company that makes cardiac devices, for $16.6 billion.

Abiomed makes a device called the Impella, that serves as a temporary heart pump that can be placed without cracking open the chest.

The Impella is the world’s smallest heart pump - the size of a pencil! - and it’s really incredible technology:

The Impella is able to pump liters of blood each minute without requiring surgery. It’s simply astounding.

It’s placed into someone’s body through a blood vessel - usually the femoral artery - and then navigated into the heart under X-ray guidance. It sucks blood out of the left ventricle of the heart and deposits it in the aorta, where it travels to the rest of the body.

There’s also an Impella-RP, which can support the right side of the heart. It’s less commonly used, but the function is the same - sucking blood out of the right ventricle and pumping it into the pulmonary circulation.

These pumps are generally used for really sick patients: patients in shock, patients undergoing extremely high risk procedures, and patients with massive heart attacks.

This is a remarkable technologic achievement, and it’s priced to match - the estimated cost per patient for an Impella is around $20,000.

I’m not an investment analyst and I have no idea whether J&J made a smart financial decision, but this is a fascinating merger to me because of the value attached to a cardiac pump that’s widely used but doesn’t have much evidence supporting that use.

I also have a lot of clinical experience taking care of patients with Impellas, and that experience hasn’t always been wonderful.

So let’s take a look at the Impella - which patients may benefit, the risks of using it, the data to support its use, and what the future may hold.

There isn’t amazing data here - and maybe that’s being too generous

It’s very clear that the Impella improves markers of cardiac function - cardiac output, cardiac index, reduced cardiac wall stress - but whether that truly translates to better outcomes remains unproven.

The patients most likely to benefit from an artificial heart pump are the sickest patients: people who are in cardiogenic shock, a condition that has a death rate approaching 50%.

But there’s never been a trial to show that the Impella actually saves lives in these patients.

The best trial of the Impella in cardiogenic shock is the ISAR-SHOCK trial, which compared Impella to a device called an intra-aortic balloon pump (or IABP).

In ISAR-SHOCK, the Impella was comparable in outcomes to a balloon pump, but didn’t save any additional lives despite the fact that it improved cardiac output in these patients in shock.

But here’s the problem - balloon pumps don’t save lives in shock patients compared to standard medical therapy.

So in shock, the Impella doesn’t have data that says it’s any better than a balloon pump, which doesn’t have any data that it’s better than just treating people with medications.

The biggest caveat here is that the absence of evidence isn’t necessarily evidence of absence.

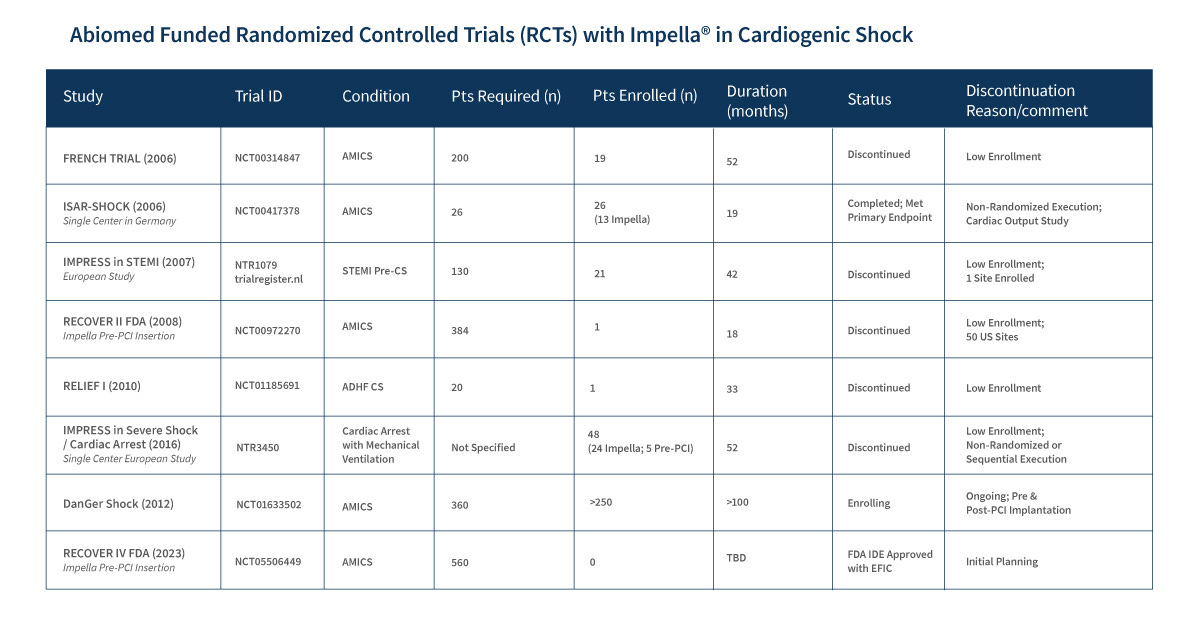

It’s super hard to enroll patients in shock into clinical trials, so there’s a real evidence gap in this group.

A quick look at the Abiomed website confirms that a lot of the planned trials have been discontinued due to low enrollment:

Limited data haven’t stopped increasing Impella use

The use of the Impella has been increasing as the technology improves and as physicians become more comfortable with the device.

This increase utilization has been particularly apparent in non-critically ill patients, although critically ill patients have seen use increase as well:

A lot of these non-critically ill patients are having Impellas placed as transient procedural support - when they are having a stent or ablation done in a high risk setting to ensure cardiac output can be maintained during the procedure.

Similar to the shock situation, we have data comparing Impella to balloon pump in the PROTECT-II trial, which showed that Impella was at least as good as a balloon pump in patients going for high risk procedures.

By providing minimally invasive support for cardiac output, the Impella enables procedures to be done that otherwise wouldn’t be technically feasible due to prohibitive risk.

My clinical experience with the Impella - it’s an amazing device that has a lot of complications

My experience with patients in shock is that the Impella can sometimes very clearly turn patients around that otherwise would have died.

You’ll find similar opinions from other doctors that use it - sometimes medications aren’t enough, and a patient needs the type of increase in cardiac output or unloading that only an Impella can provide.

And the Impella is certainly great at increasing cardiac output and forward blood flow.

The other side of the coin is that the procedural complications can be devastating.

As with all things in medicine, an Impella isn’t without risks - and these risks are why it’s so challenging to use and to demonstrate a survival benefit in trials:

Placing an Impella requires a large catheter in an artery, and that can lead to vascular problems, like cutting off blood supply to the leg and internal bleeding.

The Impella also requires that someone be on a blood thinner, which has its own associated bleeding risk.

The Impella works by sucking blood out of the heart and pushing it into the aorta, which can lead to blood cells shearing apart, a problem called hemolysis.

Since the catheter is resting inside the heart, it can also tickle the heart muscle, leading to irregular heartbeats.

In real life use, these complications are frustratingly quite common.

And the vascular complications in particular are extremely challenging to deal with.

They can be both directly life threatening (because an ischemic leg can kill you) and indirectly life threatening (because a vascular complication forces removal of the device that’s supporting your circulation).

If an Impella works without complications, it’s remarkable, and often lifesaving.

But in practice, people have complications.

And even though you can predict a bit about who will develop these issues, we don’t practice medicine with a crystal ball.

If you could guarantee no device-related complication, then the Impella is a no-brainer for a patient in cardiogenic shock. Unfortunately, there are simply no guarantees in that realm, which is why the data are so mixed when it comes to survival.

The next frontier of Impella research: unloading the heart before fixing the blockage causing a heart attack

For many years, we’ve judged the effectiveness of heart attack programs by a marker called “door to balloon time” which is the time from getting in the door of the hospital to having your blocked artery opened up during a cardiac catheterization.

But when you open up a blocked artery, you can cause something called “reperfusion injury” which paradoxically increases the amount of damage from a heart attack.

Some of the smartest people in cardiology are betting that the next evolution in acute care of high risk heart attacks is actually less about opening up a blocked artery quickly and more about unloading a heart under strain.

And that’s where an Impella comes in - by placing an Impella before you open up a blood vessel, there’s some data to suggest that you might reduce the amount of damage from a heart attack and consequently improve outcomes.

The next set of clinical trials in this area is testing the impact of “DTU” or “door to unload” times - the time between getting into the hospital and having an Impella placed to unload a heart under strain.

If door-to-unload proves itself to save lives compared to the standard of care, you’re going to see a lot more Impellas.

But that’s a big “if” because promising preliminary research doesn’t mean that an intervention will pass muster when tested in a high quality trial.

TL;DR - Impellas are amazing when they work smoothly and terrible when they cause complications

You don’t need to take care of many of these patients who turn around when they get the right mechanical support to become a believer in the power of this type of intervention.

But you also don’t need to take care of that many patients with Impella-related complications to feel like using it is a bit of a crapshoot.

There’s enough data to suggest that Impellas don’t actually lead to better outcomes (and may lead to worse outcomes and higher cost) that we should all be somewhat skeptical of their overall benefit.

The widespread use of Impellas - and the way that we all pay for their deployment in the form of higher taxes and insurance premiums - without high quality data to show that they save lives is emblematic of some of the worst aspects of modern medical care.

We should demand high quality trials to show a benefit of a device that can kill you just as easily as it can save you before we start using it all the time.

And until the FDA demands high quality trials before approval - or insurance companies or Medicare demand high quality trials before paying - we’re all going to be stuck with more questions than answers.

It’s important to have a high bar for evidence of benefit before the widespread adoption of COVID treatments and Alzheimer’s therapies as much as for cardiac devices.

A society gets the quality of evidence that it deems acceptable - and right now, I think that we’re falling short here in many areas.