A preventive valve replacement study shows the limits of the randomized trial

The way we treat problems with heart valves has been completely revolutionized over the course of the last few years.

Go back as little as 15 years, and essentially all valve procedures required open heart surgery - and came with all of the complications and recovery time that goes with cracking open someone’s chest.1

Now many heart valve procedures can be done through a catheter in the leg, and people leave the hospital within 24 hours.

Because these transcatheter heart valve procedures are much easier and lower risk than traditional open heart surgery, it’s led to questions about whether we should be doing them with different indications than we would reserve for regular surgery.2

The most common one of these valve procedures is called a TAVR, which stands for transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

TAVR is done to treat aortic stenosis, one of the most common valve problems that people develop.

A new trial looking at the timing of preventive aortic valve replacement is really interesting because it asks a provocative question about whether the timing that we use to send patients for surgery is wrong.

Let’s take a look at the EARLY TAVR study.

Aortic valve stenosis has a very bad prognosis if you don’t treat it

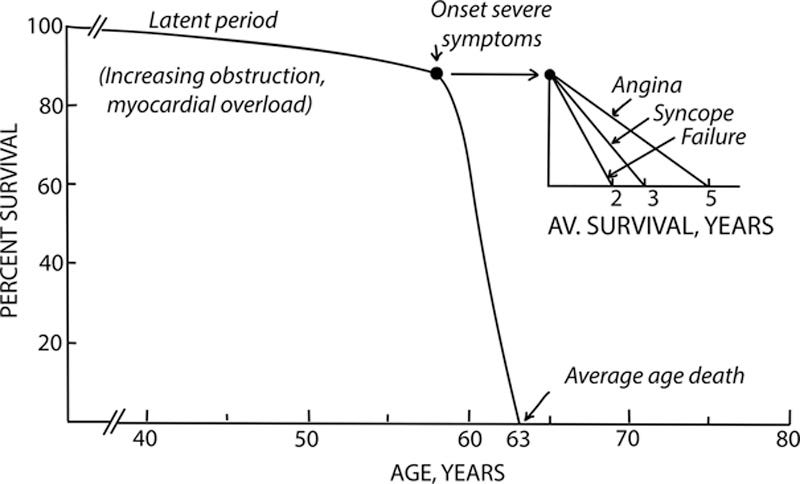

One of the most classic graphs in all of cardiology is about the natural history of severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis.3

Once a patient develops symptoms from severe aortic stenosis, it’s often quoted that their risk of death approaches 50% over the course of two years.

That comes from a paper written more than 50 years ago, looking at the natural history of patients with severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis.

Look at the curves here - you see a long period of time where survival is steady, and then once symptoms develop, survival drops off pretty rapidly:

The key word there is symptomatic, because there’s clearly a huge drop off in survival that happens when symptoms start.

The other notable part of that graph is the beginning, when survival is essentially unchanged in the patients with severe, asymptomatic aortic stenosis.

The major symptoms aortic stenosis causes are chest pain, heart failure, and syncope,4 so if someone has severe aortic stenosis5 that isn’t causing those symptoms, the current standard of care is to leave them alone and monitor them regularly until symptoms develop or their echocardiogram shows that their heart is starting to fail.6

The question about a preventive valve intervention is an interesting one

The argument to do an early intervention for a severe valve problem is quite straightforward: it’s only a matter of time before the valve issue progresses, so we can prevent you from decompensating by fixing it.

The argument against it is a bit more nuanced.

First, we don’t know whether a preventive intervention actually makes people feel better or live longer.

Second, these replacement valves don’t last forever. Doing a preventive procedure early starts the clock ticking on needing a second one.7

So the EARLY TAVR study asked the question: does doing a TAVR in a patient with severe but asymptomatic aortic stenosis improve outcomes in any meaningful way?

EARLY TAVR took patients without symptoms and randomized them to a heart procedure versus standard-of-care surveillance

Patients in this study were either assigned to getting a TAVR or standard of care with regular doctors appointments and echocardiograms.

The authors evaluated this strategy with a couple of different endpoints:

Primary endpoint of death, stroke, or unplanned hospitalization for cardiac causes

Secondary outcomes included quality of life, markers of heart function on echocardiogram, new atrial fibrillation, and death or disabling stroke

They found that TAVR reduces the composite primary outcome pretty dramatically:

This outcome was driven by unplanned hospitalization. You can see the curve for unaplanned hospitalization looks essentially the same as the composite endpoint curve:

There were numerically fewer strokes in the TAVR group, but this didn’t reach statistical significance.

The stroke finding is weird observation that doesn’t make sense to me, and I think it’s statistical noise.8

The other soft outcomes they studied assessed quality of life and subclinical echocardiogram parameters of heart function - both of these looked better in the preventive TAVR group.

Interestingly, by 5 years, 95% of patients in the study had a valve procedure done, most because of symptoms:

There was no difference in death between the groups.

This is really interesting data, but I don’t think it’s all that persuasive

The cynical read of this study is that doing a TAVR now means we don’t have to do a TAVR later.

Seriously. Look again at the curves in the unplanned hospitalization (which drove the difference between the groups):

This is a group of people who were asymptomatic at baseline. Look at what happens to those curves.

After enrolling in the trial, a third of them abruptly develop the need for an unplanned cardiovascular hospitalization in the next 4-5 months.

Then, as time goes on, they develop the need for unplanned hospitalization at the same rate as the group that had their valves replaced.

It makes no sense mechanistically to have such an abrupt increase in hospitalization with the surveillance group.

The authors hypothesize that this is related to the excellent surveillance in the study (emphasis mine):

“The lower mortality in our trial may be explained, in part, by the less invasive nature of TAVR as compared with surgery and the high quality of clinical surveillance in our trial, in which all aspects of the future TAVR procedure and care were planned before enrollment. This led to prompt conversion to aortic-valve replacement, with 87.9% of patients undergoing the procedure within 3 months after symptoms developed or aortic-valve replacement became indicated.20 This level of vigilance may not be replicated in the real world, especially in care contexts in which aortic stenosis is undertreated.”

So patients were primed before enrollment in the trial that they would eventually need a valve replacement and then just after being enrolled in the watchful waiting arm, many developed symptoms requiring urgent intervention?

I suspect that a lot of those events in the first few months are related to a reverse placebo effect - people expected to develop symptoms soon, so they developed symptoms soon.

Neither of the hard outcomes - death and stroke - were different between the groups.

The conclusion here is a nothing-burger: an early TAVR is fine, but it’s not lifesaving

The top line result of this trial looks really impressive - the conclusion from the study is that early TAVR makes outcomes better.

The authors state: “a strategy of early TAVR was superior to guideline-recommended clinical surveillance in reducing the composite end point of death, stroke, or unplanned hospitalization for cardiovascular causes.”

That’s not wrong, but it is totally misleading.

Early TAVR doesn’t save lives, doesn’t prevent strokes, and doesn’t prevent atrial fibrillation.

It just prevents you from having to do a TAVR later.

How you look at the results of a study make the difference between whether you’re persuaded to change your decision making or whether you aren’t.

As long as patients with asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis remain asymptomatic, there’s no urgency to send them for a procedure - and digging into the details of the EARLY TAVR results makes me feel confident that strategy is totally fine.

I’m going to continue my current practice of frequent monitoring and regular visits to assess for the presence of the symptoms of severe aortic stenosis: chest pain, shortness of breath, and lightheadedness or passing out.

I commonly described valve problems to patients like this. The heart has 4 valves, which are kind of like doors. The purpose of valves is to make sure blood flows forward and doesn’t flow backwards. Valves can have two problems - they can get tight (termed stenosis, like a door with rusted hinges) or they can get leaky (termed regurgitation, like a door that flops back and forth). Untreated valve problems progress slowly, but they generally tend to progress. When valve problems become severe, they can cause symptoms of heart failure, chest pain, or even sudden death. Because these are mechanical problems, they require mechanical solutions. Medications can only temporize the issue but they don’t actually solve the problem at all.

Transcatheter means it’s done through a catheter, which is the medical word for tube. An IV is a catheter, it doesn’t mean it’s done through a urinary catheter, which has become the most widely known/publicized version of a catheter.

As mentioned in footnote 1, stenosis means a tight heart valve. Regurgitation is the other problem, which means a leaky heart valve. Insufficiency is sometimes used interchangeable with regurgitation, because doctors are pretentious and like to have more than one way of describing something.

Syncope means passing out or fainting.

Valve problems are graded on a scale of mild, moderate, and severe. Valve issues don’t cause symptoms until they are severe. So if you’re going back over your old echocardiogram to see whether you have any of those symptoms, keep in mind that mild or moderate valve disease doesn’t require any intervention other than serial monitoring with echocardiograms.

There are specific criteria for echocardiogram parameters that differ based on different valve issues that suggest subclinical decompensation which would have us recommend a valve intervention before symptoms develop.

Lifespan of these valves is approximately 10 years, although there is considerable inter-individual variation in how long they last. For aortic stenosis, we can generally do a second transcatheter procedure, but more than that starts to get dicey. So if your life expectancy is longer than 20 years, it may actually be better to do a surgical procedure and get a metal valve placed that lasts forever. Each case is different and these general guidelines can’t be specifically extrapolated to any individual patient.

The stroke difference doesn’t make sense for a few reasons. First, there’s no real mechanism by which untreated severe aortic stenosis should cause a stroke. The TAVR procedure itself can cause a stroke (by dislodging calcium from the native aortic valve when the new valve is put into place), but untreated valve disease shouldn’t increase that risk. The other mechanism I can think of is if untreated valve disease increases the risk of atrial fibrillation (which increases stroke risk), but those numbers weren’t any different. So I think it’s likely that this difference is due to chance.