Statins are better than you think they are

A return of my newsletter with some new thoughts about an old issue

I’m excited to bring this newsletter back after a few months away on a paternity hiatus.

The time away hasn’t been a vacation, as anyone who has had a new baby at home can attest (and I’ve been seeing patients throughout much of my “leave” so it hasn’t even been time away from work).

I’ve missed the clarity of thought that can only come with the actual act of writing, as no activity helps turn amorphous thoughts into tangible ideas like writing does. I’ve also missed the give and take with readers, and I’m very appreciative of those of you that take the time to read my work and send me your comments.

And so while this newsletter may not have been keeping up to date with the newest developments in the world of Omicron subvariants and Monkeypox, I don’t think that we’ve missed that much.

I’ll certainly get into my current COVID/vaccine/masks perspective, but the most important stuff in medicine is almost never happening in the world of the news.

I think that’s partly because you can’t separate the signal from the noise without considerable amounts of data, analysis, clinical experience, and, hindsight. But it’s also partly because our attention is usually directed towards things that are novel rather than things that are important.

And so while this newsletter is going to continue to be on the reactive side - providing a doctor’s perspective on the medical topics that are receiving current attention - I’m also going to spend time on the evergreen topics that I’m still constantly reading and thinking about.

Today’s newsletter is about a topic where my thinking is evolving, and also the one that I get asked about on a day to day basis more than any other - statins.

A lot of my patients hate statins - or at least hate the idea of them

I’m often surprised by how much pushback I get when I recommend that patients go on statins like Crestor (rosuvastatin) or Lipitor (atorvastatin).

Sometimes the pushback is grounded in doubt about whether the medicine is appropriate: “How come I should take that if I’ve never had a heart attack?” or, more commonly, “I really don’t want to take Lipitor if I don’t have to.”

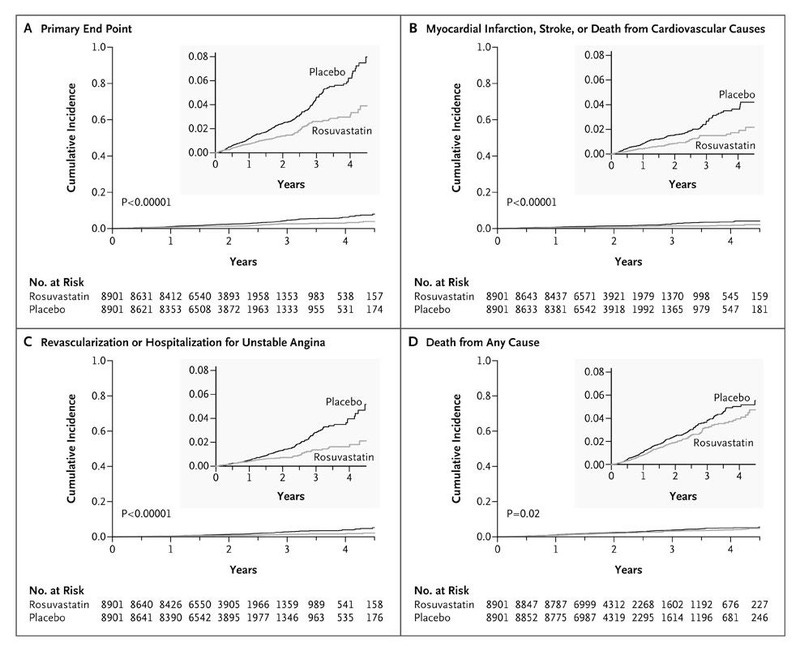

Sometimes it’s grounded in real fears about side effects: “I heard those things make your muscles hurt and cause diabetes.”

Sometimes it’s grounded in hearsay: “I had a cousin who started on a statin and got dementia who hasn’t been the same since.”

And sometimes it’s based on something that they read on the internet. And there’s a *ton* of hate on the internet about these drugs:

But statin distrust isn’t just folks with an internet platform - it’s very much in academia, too

Some of the most highly regarded academic cardiologists also suspect that we overprescribe these medications and that, for many, the risks greatly outweigh the benefits.

Take a look at this piece from Rita Redberg - probably one of the smartest cardiologists on the planet - talking about the weakness of the data on statins for those who have never had a heart attack (medical term = primary prevention). I’ve watched interviews with Dr. Redberg where she discusses her frequent de-prescribing of statin therapy in those who don’t need them.

There was a recent meta-analysis in JAMA Internal Medicine that got a lot of attention for it’s findings on the unimpressive benefit of statin use, concluding skeptically that:

“The study results suggest that the absolute benefits of statins are modest, may not be strongly mediated through the degree of LDL-C reduction, and should be communicated to patients as part of informed clinical decision-making as well as to inform clinical guidelines and policy.”

Why are some of the most prescribed drugs of all time inspiring so much distrust?

Most of the anti-statin attitudes that I’ve seen fall into one or more of the following groups:

Statins aren’t proven to work in healthy people who don’t have heart disease, so a lot of prescriptions are given to people who won’t benefit

Statins really aren’t all that protective against heart disease

Statins are risky drugs, and because of their potential to cause dementia and diabetes, the risks often outweigh the benefits

Statins are poorly tolerated and way too many people have side effects

I’ve already written a rebuttal about why I am confident that the people who don’t think that LDL-cholesterol (and other apolipoprotein-B containing particles) plays a causative role in cardiovascular disease are wrong.

And while there may be big money in getting people fat, sick, and medicated, in reality, the practice of medicine is simply too fragmented to make statin prescribing a real conspiracy.

But the harder voices to rebut are the ones who simply think that we overprescribe these medications to healthy people. In fact, I used to be in this group.

These folks are correct that there isn’t high quality evidence showing a gigantic benefit of statin use in low risk people who haven’t had a heart attack. It’s wrong to say that there isn’t any evidence, because there is. But that evidence is certainly mixed, to be generous.

And we’ve certainly never had a trial looking at giving healthy 40 year old statins for 3 decades to see if they lower heart attacks and strokes.

So if the direct evidence isn’t all that compelling, aren’t the skeptics right?

I think that how you view this question ultimately boils down to what type of extrapolation of the evidence you think is reasonable versus unreasonable.

A literal read of the data that we have says that there has never been a trial showing a benefit in giving statins to young people without metabolic syndrome and without heart disease.

But no one knows if that’s because we’ve never done a long enough trial with enough people to show that this benefit exists or because healthy people actually don’t benefit.

I think it’s worth keeping a few additional points in mind as we evaluate this question:

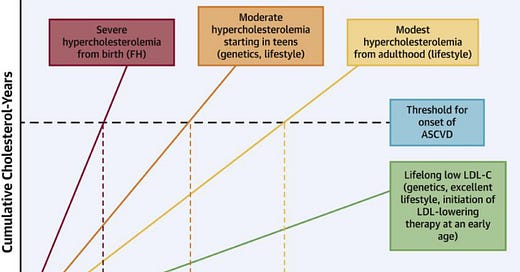

Cardiovascular disease doesn’t happen over the course of years, it happens over the course of decades.

There’s significant evidence that the impact of having low LDL-C over the long term reduces cardiovascular disease considerably.

Statins have been shown to reduce heart disease and probably reduce death from any cause, so they aren’t just drugs that lower a biomarker but don’t impact things that we care about.

The magnitude of benefit you get from medical therapy is dependent on the degree and length of time of LDL-C lowering:

For most people, these drugs are well tolerated with minimal side effects.

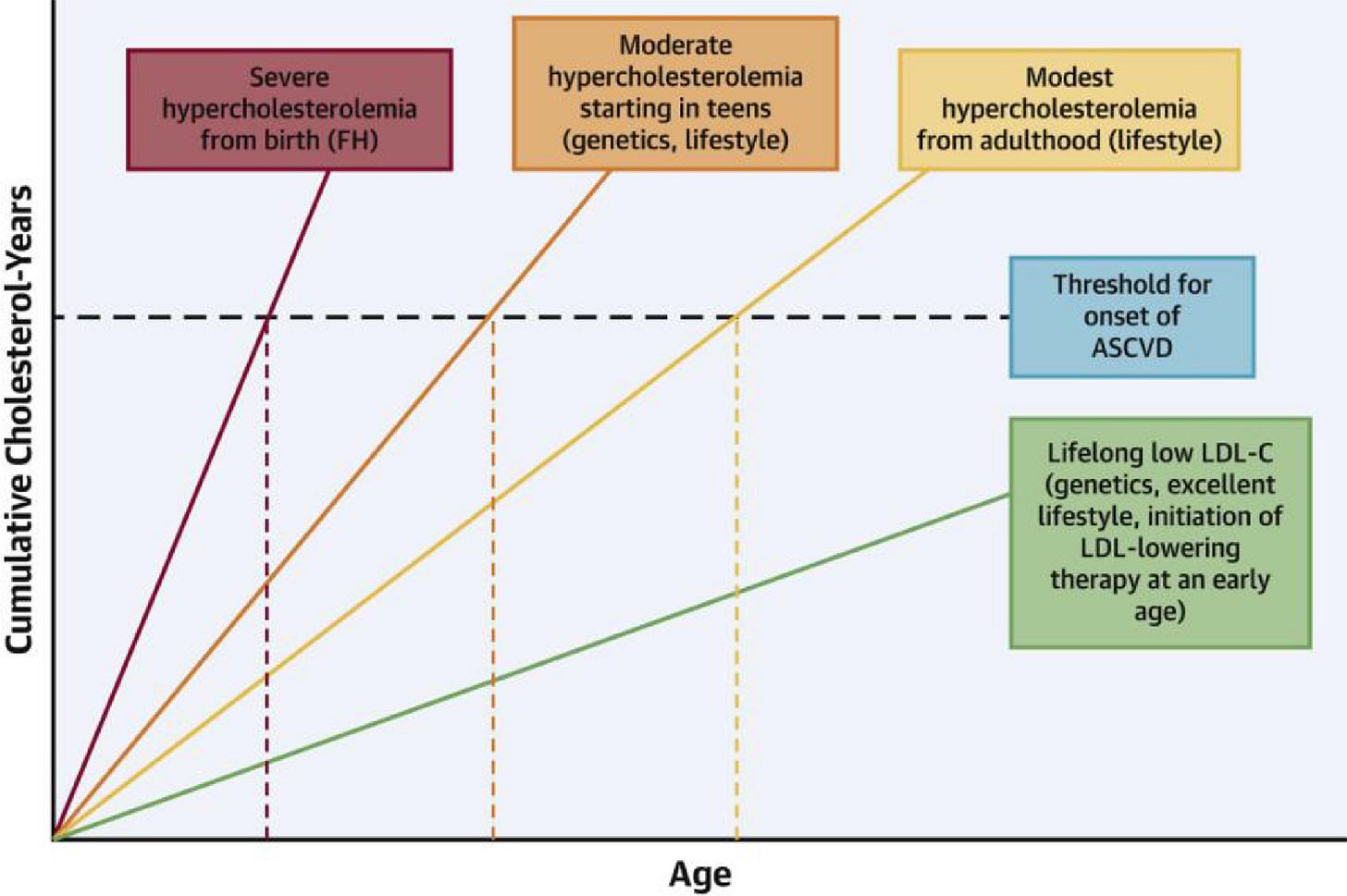

The clinical trials on statins (and other lipid lowering drugs) show diverging risk that gets bigger over time. Take a look at this graphic from the JUPITER trial on rosuvastatin (Crestor) in patients with no history of heart attack or stroke, where the trend lines show ongoing divergence over the years:

I think it’s fair to say the following:

Heart disease takes place over the course of decades.

Statins are safe and effective drugs at lowering lipid numbers that are well tolerated by the majority of people who take them.

Low lipid numbers over the course of a lifetime leads to very low risk of heart disease.

Lowering numbers over the short term leads to a small reduction in cardiovascular disease, and the benefit increases in magnitude over time.

As I’ve been digging into this data more and more, I’ve become more persuaded on the long term benefit of lowering our lipid numbers.

As a consequence, I’ve started to have a much lower bar to prescribe statins for patients than I used to.

I agree with the skeptics on one thing: this hasn’t been proven definitively.

But I don’t think it’s insane to have this take on the body of the medical literature. I see the skeptical side of things, but I don’t agree with it in this case.

When it comes to cardiovascular prevention and lipid numbers, lower certainly does appear to be the right call, and lower for longer seems even better.

Thanks again for reading! I really appreciate the support of my readers, and I welcome comments and questions that my newsletters bring up.

As always, I would very much appreciate you sharing this newsletter if you find the content valuable or interesting.