Gene editing for heart disease

Not yet ready for prime time, despite what the NY Times tells you

The American Heart Association hosted its annual meeting this past weekend in Philadelphia.

A lot of really interesting new studies were presented, and you may have noticed that some of this work made it into the mainstream press over the last few days.

I thought it would be interesting to go through some of the new trials that were presented this past weekend.

I’m going to make the AHA Conference Recap into a handful of different newsletters rather than just one big one.

So with that intro, let’s take a look at a potential paradigm shift in cardiology - gene editing to treat heart disease.

Verve Therapeutics is testing gene editing as a heart disease treatment

You should read the New York Times article on the VERVE-101 study presented at the AHA conference to get more background.

And then you can look at the data that they actually presented here.

The treatment that the VERVE-101 study tested aims to edit the PCSK9 gene in liver cells. This gene is linked to lifelong low LDL-C and very low risk of heart disease.

I wrote about PCSK9 here, if you want additional context.

The investigators looked at 10 patients who received the treatment, which uses lipid nanoparticles to help the CRISPR based gene editing machine into liver cells:

The treatment seems effective at working in liver cells in a test tube.

It also seems safe and effective in non-human primates.

And now it’s being tested in humans.

Is VERVE-101 gene editing effective? It certainly seems like it lowers LDL cholesterol

There was a dose dependent decrease in LDL-cholesterol levels after treatment, with the highest dose patient experiencing a 60% reduction in LDL that lasted for at least 6 months after a single infusion:

That’s pretty cool and in line with what you’d expect - a drug that edits your DNA encoding a gene that influences LDL-cholesterol should have a long effect - it should be lifelong, but they only reported a few months of data.

But let’s keep in mind what this doesn’t tell us: Anything at all about whether this cuts heart disease risk.

I’m going to repeat that: this tells us nothing about what this treatment does to heart disease risk. We don’t know if this reduces heart attacks, strokes, or death from heart disease.

It’s a really big gap, and worth emphasizing before you get caught up in the excitement.

The other big issue here: *major* safety concerns

There were two major concerns about safety here:

A rise in liver function tests, which makes sense with a treatment that edits DNA in the liver

Major concerns about cardiovascular toxicity, which is alarming about a drug that is supposed to prevent heart attacks.

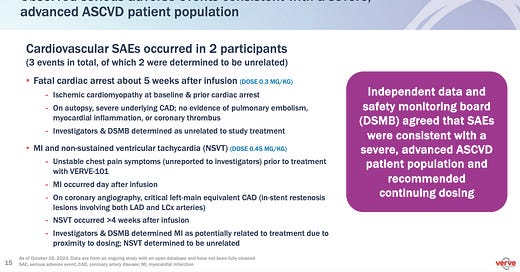

I’m going to put up the whole slide from the Verve presentation here, so you can read what they wrote and how they interpreted it:

Out of 10 patients who received this treatment, 2 had major cardiovascular adverse events.

One had a fatal cardiac arrest 5 weeks after the infusion. The independent data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) concluded that it was unrelated to the treatment.

Another patient had a heart attack the day after receiving the investigative treatment, and was found to have a critical, high risk blockage from obstruction of prior stents in his heart.

The DSMB conclude this was potentially related to treatment.

What’s going on here? What does it mean?

When it comes to the safety side effects, I’m pretty alarmed - this is scary stuff and raises major questions.

I’m not quite ready to say that we should halt work on gene editing treatments to reduce heart disease risk - but some smart doctors are.

Read this from Venkatesh Murthy for the perspective on why it’s time to shut this down right now.

The argument against gene editing for heart disease is straightforward:

This isn’t a disease where there’s a large unmet need for treatment. We have a bunch of safe and effective treatments that have well established track records of efficacy and safety: statins, ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors, bempedoic acid

There is real concern that there may be cardiac toxicity from this therapy. It’s unclear if this may be related to the gene editing itself (less likely) or the lipid nanoparticle (LNP) delivery system, similar to Covid mRNA vaccines that cause an inflammatory response (more likely)

We don’t understand this technology well enough in the earliest generations to gamble screwing it up with bad outcomes on a disease that already has quite a few successful treatments. We should focus CRISPR research on treating diseases that don’t have great options and are also single gene problems, like sickle cell disease

I find these arguments compelling, and I would never personally enroll in a trial like this or send a patient to enroll in a trial like this.

But I also have a ton more questions about gene editing treatments. To list a few:

How confident are we that there are no off target edits? Are we looking at every other tissue in the body? How do we search for it and how long do we need to search?

How long does this last for? Is it really permanent editing?

What are the long term effects? When I give a drug for a long time, I feel confident that the side effects will go away when we stop the drug. With CRISPR, not so much

I’m less interested in the existential or ethical questions here, mainly because everyone is going to have an opinion on this and I’m more curious about how we balance risks and benefits than I am about how it makes me feel.

Is this playing God? Yes, I think so.

Is editing our DNA wrong? No clue, above my pay grade.

This got a bit longer than expected - we’ll try to cover some of the other studies from AHA this week with a bit more brevity.