Go get your Lp(a) checked!

I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve written in this newsletter about the importance of taking control of your own health by getting information about your medical status.

That means doing things like monitoring blood pressure and weight, but also getting bloodwork done to see the things that don’t show up with symptoms but are potentially leading indicators of dysregulated health and increased risk of chronic disease.

I’m talking about checking things like:

A standard liver panel - seeing even a small rise in ALT or AST can be a potential early sign of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and fatty liver. And you shouldn’t just use the standard reference range of what’s “normal” here: because of the obesity epidemic, the standard has actually been shifting since so many people have fatty liver

Your blood sugar - not just on a basic metabolic panel, but in the form of a hemoglobin A1c, which is a marker of average blood sugar over the last 2-3 months. It’s not a great test to distinguish between borderline abnormal and optimal, but it does do a good job of discerning whether you have longstanding uncontrolled diabetes

Your cholesterol panel - yes, all cardiologists think about your LDL-cholesterol, but that’s not all there is to heart disease. A look at the triglyceride to HDL ratio can tell you quite a bit about your risk of heart disease even if the LDL is in the “normal” range

But I’m not writing today to talk about the standard stuff. Today we’re talking about Lp(a).

This newsletter comes with an instruction: if you haven’t gotten your Lp(a) checked, you should get it done if you’re interested in understanding your heart disease risk.

What the heck is Lp(a)?

Lp(a), pronounced el-pee-little-ay, is the shorthand for lipoprotein(a), a particle that carries cholesterol through the bloodstream that’s a major player when it comes to premature heart disease risk.

Lp(a) is actually an LDL particle that’s linked to a protein called apolipoprotein-a (which is different than apolipoprotein-A-1, the protein on an HDL particle).

The nomenclature gets confusing quickly.

But Lp(a) matters quite a bit because high levels lead to increased cardiovascular risk.

If you follow the news, you may remember when Bob Harper, the personal trainer from The Biggest Loser, had a heart attack and a cardiac arrest in 2018. Despite exercising, eating well, not smoking, and in general taking care of himself, Mr. Harper technically died but had his life saved by a heroic bystander at the gym who started CPR quickly and got him to the hospital.

Bob Harper had really high levels of Lp(a), and that’s almost certainly why he had a heart attack at age 52 despite “doing everything right.”

Why is Lp(a) bad?

Lp(a) is bad for 3 major reasons:

Lp(a) accelerates atherosclerosis (AKA cardiovascular disease). The Lp(a) particle is very effective at getting into the walls of blood vessels and getting stuck there

Lp(a) increases inflammation and oxidation. When cholesterol gets into the walls of your blood vessels, it only causes problems if it’s oxidized and incites inflammation there. Lp(a) accelerates both of these processes

Lp(a) increases blood clot formation. There’s an area on the Lp(a) particle called kringle repeats that have a similar structure to a substance in our bodies called plasmin. Plasmin activates blood clotting, so something that is structurally similar like Lp(a) can cause blood clotting as well.

There are hypotheses that the increase coagulation associated with Lp(a) may have provided an evolutionary survival advantage due to a decreased risk of bleeding out from trauma, but that’s only a guess at this point in time.

You can actually add a fourth reason as well: high levels of Lp(a) increases the risk of developing a tight aortic valve (medical term: aortic stenosis) that requires a valve replacement procedure.

What are normal Lp(a) levels?

Across a population, the majority of people have Lp(a) under 50mg/dL and almost everyone is under 100mg/dL:

Who should we worry about as having high Lp(a)?

Lp(a) tends to be primarily something that’s genetically governed. Although diet and exercise are the foundations of avoiding heart disease, apart from some small research, they don’t seem to impact Lp(a) levels all that much.

About 10% of the population has high Lp(a), but risk is proportional to the degree of elevation:

When you hear about someone having a heart attack under the age of 40, in my eyes it’s almost certainly Lp(a) until proven otherwise.

When you hear about a family where everyone gets bypass surgery before they turn 50, you think strongly consider Lp(a) as the culprit.

South Asians in particular are a group where Lp(a) is likely responsible for a considerable burden of premature cardiovascular disease, but elevated Lp(a) can be found in any race or ethnicity.

If Lp(a) is high, what can we do?

There’s often an argument made in medicine that if a test isn’t going to influence your management, you shouldn’t bother ordering the test.

Lp(a) brings up an interesting question through that lens: since we don’t have any treatments that are specifically targeted at this particle, what’s the point of getting this info?

One argument I’ve made before is that empowering patients to understand risk is a big deal.

But knowing Lp(a) doesn’t just empower a patient - it changes the way that I treat someone, both with regards to diagnostic testing as well as treatment.

If Lp(a) is high, I am more aggressive with managing other risk factors - I’m more likely to recommend antihypertensives and lipid lowering drugs, and I’m definitely a bit more aggressive with checking a calcium score for personalized risk prediction.

And knowing someone’s Lp(a) status changes my tone when discussing lifestyle changes - the higher your Lp(a), the more emphasis I’m going to place on the importance of being careful with your diet and optimizing your exercise, even if I don’t have a specific Lp(a) lowering treatment.

The impact of the medicines we have on Lp(a) is a bit surprising

You may be surprised to learn that statins (the medicines most commonly prescribed to reduce heart disease risk) actually raise levels of Lp(a). That doesn’t mean that they increase risk - the evidence on statins is pretty clear that they lower heart disease risk, even in patients with high Lp(a).

PCSK9 inhibitors - like alirocumab (Praluent) and evolocumab (Repatha) reduce Lp(a) and they seem to have a bigger benefit the more they lower Lp(a).

Niacin (AKA vitamin B3) is a drug that used to be used for cholesterol lowering until we found that it has no effect on heart disease risk (and seems to increase the likelihood of developing metabolic syndrome).

Niacin lowers Lp(a) levels, but it doesn’t seem to reduce heart attack risk.

Here’s a table summarizing the impact of treatments that we have on Lp(a) levels:

The drugs to target Lp(a) are currently in clinical trials

The HORIZON trial is currently ongoing to test the effect of a drug that blocks the production of apolipoprotein(a) - and thus inhibits development of Lp(a) - on the risk of cardiovascular disease.

But this is a situation where you need to wait for the trial here. The history of cardiovascular disease drugs is littered with examples of things that should work based on our understanding of the biology but ultimately don’t work - or increase death! - when tested in a high quality study.

The bottom line: elevated Lp(a) is bad, but knowing your level let’s you and your doctor more personalize your prevention

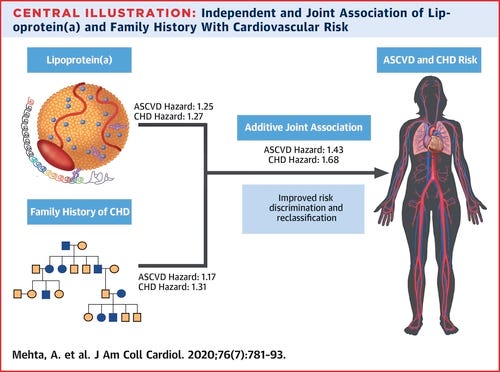

The combination of knowing Lp(a) and family history are really powerful additions to standard cardiovascular disease prediction algorithms, which don’t incorporate them.

I am a firm believer that checking Lp(a) once in life is a vital component of cardiovascular disease prevention.

I certainly check in every patient who comes to see me for a preventive evaluation.

A high Lp(a) changes my threshold for treatment and testing, particularly when it’s coupled with a family history of heart disease.

The only way to take control of your health is to know your numbers. And Lp(a) level is a vital number to know!

Thank you for reading! Please share with friends and family and encourage them to subscribe!

Disclaimer: this is my opinion, not medical advice. Reading this newsletter does not constitute the formation of a doctor-patient relationship and is no substitute for the opinion of your doctor.