Intermittent fasting doesn't work - unless it works for you

The challenges with studying an intervention like this

The question of “does this diet work?” can be an endless topic for debate.

The people who really feel strongly about this stuff will talk your head off about studies on nutrition to try to persuade you that their preferred way of eating is the most proven.1

No matter what your nutritional tribe is, there’s a study showing that it’s the best one.

But in the real world, when results matter more than virtue signaling about trusting the science, you have to answer the annoying question of whether it works for the person in front of you.

This is the major place where nutrition research falls short - in the real world, when results matter more the p-values.

So when a new randomized controlled trial on intermittent fasting is published, it’s worth understanding.

The top line result was unimpressive, or as the media described, “challenging the benefits of intermittent fasting.”

But let’s look into what this actually showed and, more importantly, what we can learn from research like this as it applies to our own lives.

Just so we have a shared mental model - do you know what intermittent fasting is?

The term intermittent fasting is the way that regular people describe a concept that nutrition researchers call “time restricted feeding” or TRF.2

Intermittent fasting in this context means that all eating is done during period of several hours (varies by study) and then during the rest of the day, people are instructed to fast.3

In this most recent study, they used an 8-10 hour window of eating, which means 14-16 hours per day in which people do not eat.4

Depending on who you talk to, you will see different protocols recommended regarding the eating/not-eating time window.

This new study looked at the impact of intermittent fasting on people with metabolic syndrome

This trial randomized patients with metabolic syndrome to either intermittent fasting plus dietary recommendations to eat a heart healthy Mediterranean diet or just giving dietary recommendations alone without instructions on the timing of when to eat.

They looked at a number of different parameters around their metabolic health.

The most interesting aspect of this study is the data collection - they had all the participants wear a continuous glucose monitor, or CGM, for a portion of the trial, and they did body composition analysis with DEXA scanning before and after.5

They also measured their sleep and activity with a wrist monitor.

They followed people for 3 months, with a handful of touchpoints along the way:

It’s a cool study design, and having the data from the CGM, DEXA, and activity tracker are both interesting and novel pieces of information for us to have.

One thing I will note - the 24 hour diet recall with a dietitian is a way better method of assessing calorie intake than most nutrition research uses, but it’s still imperfect as figuring out what and how much people are eating.6

They found that - on average - intermittent fasting had a very small, but positive impact on blood sugar and weight

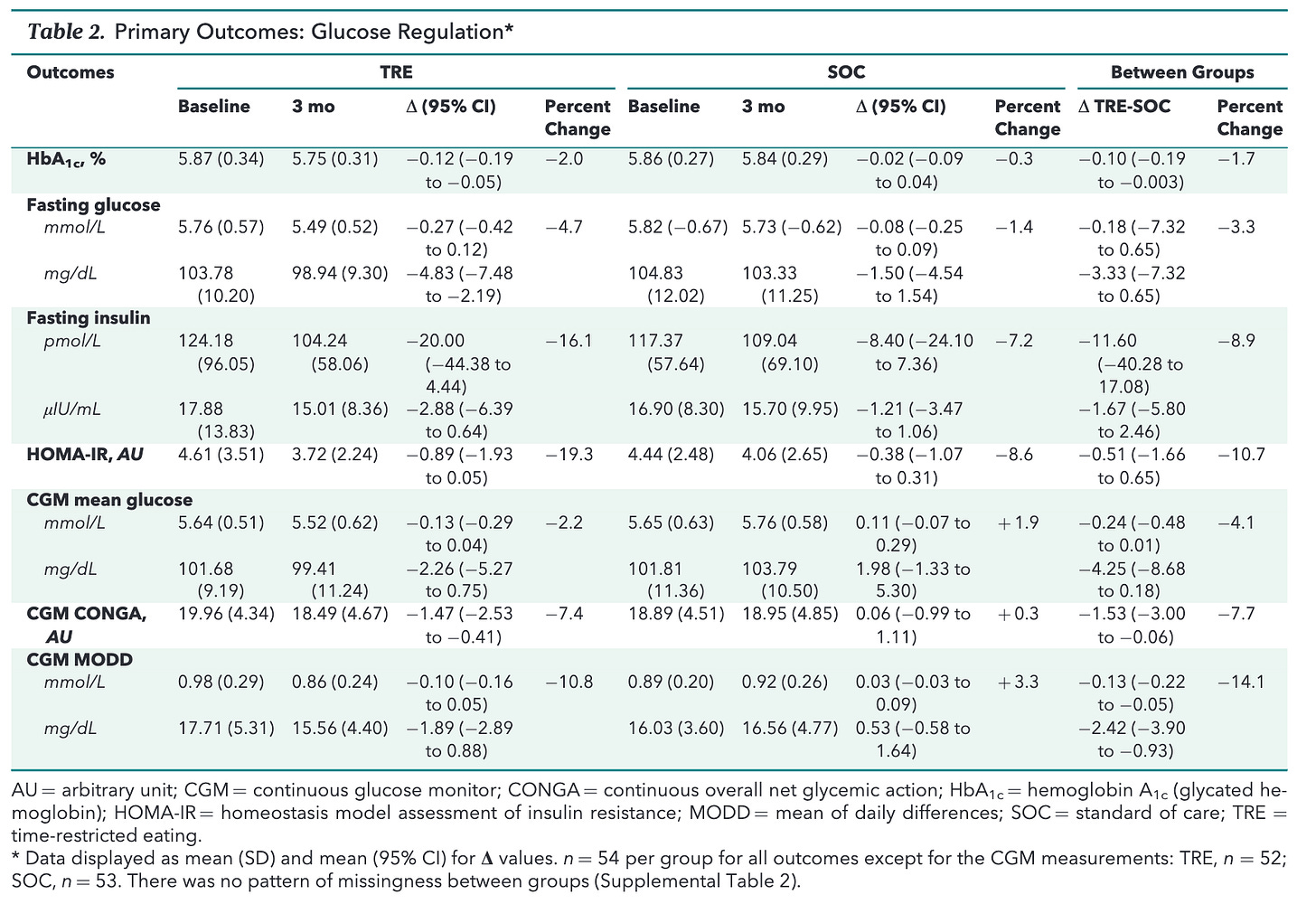

The table with data from the study is a bit tricky to read, but I’ll put it here in case you want to go through the details:

I actually found this graphic from the supplementary appendix on metabolic syndrome parameters way easier to digest and more useful to see.

It’s a look at how many people met each number of criteria for metabolic syndrome7 at the beginning of the study and then at 3 months:

It’s interesting to contrast the complicated table from the graphic on patients meeting criteria for metabolic syndrome - it shows that a 3 month period of time can move the needle a bit on criteria for metabolic syndrome.

Some people have their health improve with intermittent fasting. And some don’t.

Some people have their health improve on following standard of care diet advice. And some don’t.

It’s fascinating to see what I took from the paper versus what gets put into a news article on this

I look at this as a useful study - intermittent fasting was a method of restricting calories that led to improvements in glucose control and weight for patients.

But not everyone sees it like this. As some articles describe: New Johns Hopkins study challenges benefits of intermittent fasting

But patients overall seemed healthier after both the intermittent fasting protocol and the standard of care.

So why is it that this study challenges the benefits?

Doesn’t it just suggest that this is a strategy that might be useful?

Here’s the most important take home - if intermittent fasting works for you, that means it works

The most important graphic I’ve ever seen in a paper on diet comes from the TREAT trial, a study looking at intermittent fasting that I wrote about a couple of years ago.

This is a graphic about the weight loss or weight gain of individual participants during a trial looking at intermittent fasting (TRE) versus consistent meal timing (CMT).

Each bar on the graph represents an individual patient:

What do you see there?

There’s a huge variability in what happened to different people in the study!

Each of those bars represents a person - some people gained weight, some people lost weight, some people had no difference.

I suspect that any diet that you study is going to have a similar variability from person to person.

My clinical experience with this mirrors that graph: different people respond to different types of changes differently.8

Understanding what’s going to work for you, and more importantly, what you’re going to stick with, is the important thing here.

It’s not what the “studies” say.

So when it comes to intermittent fasting, if it works for you then that means that it works.

You’ve probably heard the joke, “how can you tell that someone is a vegan?” A: because they told you! You can also replace “is a vegan” with “does CrossFit” and the joke is equally funny.

I’m going to use intermittent fasting instead of time restricted feeding, even though TRF is the more technical scientific term. I think that most people know what intermittent fasting is, but time restricted feeding is less well known.

There’s a whole set of theories about whether this is a long enough time without food to induce the major theoretical benefit of true fasting - inducing autophagy, which is what you’ll hear influencers talk about all the time. Autophagy is a normal cellular process of recycling, thought to be a way that our bodies get cleaned out during periods of severe calorie restriction. There are two major gaps here - one is that intermittent fasting as practiced probably doesn’t cause humans to have significant autophagy, and the second is that we don’t really know enough the role of autophagy induced by diet in actually improving outcomes for people dealing with chronic disease.

The “fasting” window includes when you are sleeping.

CGM is continually measuring your glucose via a sensor on your skin that looks at interstitial fluid sugar content as a surrogate for blood sugar. It’s considered the best way of measuring glucose levels in patients with diabetes.

Part of the reason nutrition research is so useless overall is that the method of data collection commonly used is something called a “food frequency questionnaire.” It’s worth looking at one of these and then thinking about how realistically it can accurately assess what you eat (very poorly for almost everyone) and then realize that almost all nutrition research that you read about is based on this crappy data. Garbage in, garbage out.

The criteria for metabolic syndrome are the same things that you would think about as being classic markers of poor health: abdominal obesity, elevated triglycerides, low HDL, elevated blood pressure, elevated blood sugar.

The reason for these differences is pretty complex. I suspect some are biologic/genetic, some are psychologic, some are environmental. It’s tough, if not impossible, to tease out the why here. I think of it as similar to the reason why some people like oranges and some people don’t.