Common medical problems often have a lot of unanswered questions about their management.

The gap between what we know and what we would like to know is really big - that’s part of why practicing medicine never stops being interesting.

But to answer a seemingly simple question is often quite challenging, as the data that we have doesn’t cover every clinical scenario and new data is always creating new questions.

Last week I wrote about a common, unanswered question when it comes to atrial fibrillation, one of the most common irregular heartbeats: how much Afib means you have Afib?

This week, I want to tackle a different question.

Does ablation, one of the most common procedures used to treat (and potentially cure) atrial fibrillation have the potential to be a lifesaving procedure?

A quick primer on afib ablation

You could write a million newsletters on this one procedure alone, but I think it’s worth a brief intro into what an ablation is.

Irregular heartbeats are caused by abnormal electrical impulses in the heart.

An ablation is a technique of modifying the heart’s electrical system to reduce or eliminate abnormal electrical impulses.

For an afib ablation, the most common modification is something called PVI, or pulmonary vein isolation, the area of the heart where many of the abnormal electrical impulses originate in afib.

The procedural details and potential complications can be confusing, but that’s a good enough primer to start.

The theory behind why an ablation might be lifesaving is probably different than you think

As I wrote last week, I always tell my patients that Afib matters for 2 major reasons:

It increases your risk of stroke

It can make you feel unwell

So it should follow logically that an ablation for afib might help to save lives if it reduces stroke.

After all, around 150,000 people die in America each year from stroke, so it’s certainly plausible.

But stroke reduction after afib ablation is controversial topic - many cardiologists will continue anticoagulant therapy even long after a successful ablation.

This is partly because in many cases, we don’t know if afib actually caused the stroke (in which case ablation should reduce that risk), or whether its presence is simply a marker for increased stroke risk from multiple mechanisms (in which case ablation wouldn’t be likely to have an impact on stroke risk).

It’s also worth noting that the CABANA trial, one of the largest trials looking at outcomes for patients randomized to ablation versus medical therapy didn’t find a difference in stroke or death for patients who underwent atrial fibrillation ablation:

But there’s another theory that may account for why afib ablation could be lifesaving - the progressive myocardial fibrosis theory.

I told you that there are two major problems with Afib, which is an incomplete way of characterizing things

There’s an additional theory about why Afib can often be problematic: the progressive cardiac dysfunction theory.

For a small group of people, the presence of Afib itself can cause structural heart disease through a couple of different mechanisms:

Left atrial dilation leading to mitral regurgitation (to be precise, atrial functional mitral regurgitation)

Progressive heart muscle scarring and resultant dysfunction (the progressive myocardial fibrosis theory)

Direct and indirect effects from the abnormal rhythm itself (loss of atrial kick or a tachycardia mediated cardiomyopathy, respectively)

The end result is that Afib can cause heart failure through a number of different pathways.

To be clear: most people with Afib do not develop these problems.

If you have afib (or know someone who has afib), I am not suggesting that this is likely to happen to you. But unfortunately we don’t have good predictive methods of figuring out who is going to develop heart failure as a consequence of longstanding atrial fibrillation.

The suggestion that Afib ablation might be lifesaving in heart failure hits prime time in 2018 with CASTLE-AF.

The CASTLE-AF trial put this issue on the map for me when I think about the validity of the progressive cardiac dysfunction model as an argument for Afib ablation.

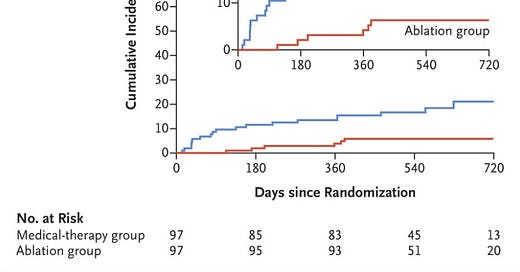

CASTLE-AF was published in 2018 and followed patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction randomized to Afib ablation versus medical therapy alone.

They found that Afib ablation reduced the risk of death considerably:

Look at the vertical axis - in the group that just got medical therapy, 25% of the patients had died at 3 years!

And it takes a while for the curves to separate, which suggests a long term effect on cardiac remodeling effect from the Afib ablation rather than a direct impact from being out of Afib.

There are caveats here - this is a really small trial (look at total numbers under 200 in each group), there was no sham procedure, and the results seem almost too good to be true.

And so I think most people saw CASLTE-AF as an interesting study in need of further investigation, not as a new paradigm for treating every patient with heart failure and Afib.

And now CASTLE-HTx comes in and adds more evidence to this area

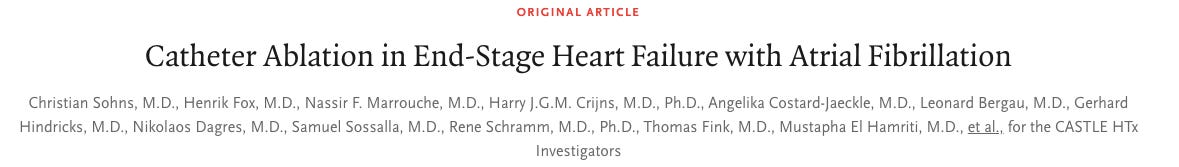

CASTLE-HTx. is a trial done by a lot of the same investigators, and they looked at much sicker patients in this trial.

This is a clinical trial that was done on a group of patients with end-stage heart failure referred for heart transplant evaluation - the sickest of the sick.

They randomized this group of patients to a similar treatment as CASTLE-AF: Afib ablation versus medical therapy alone (this is a small trial with about 100 patients in each group).

The results were similarly striking. A huge reduction in death and need for either artificial heart or heart transplant:

The survival curves separate almost instantly:

When survival curves separate so early, you have to wonder whether there’s something different between the groups that confounds the analysis.

But based on a review of the methods and the patient characteristics, it seems like this was a true randomized trial that should drastically reduce the chance of unmeasured confounders (although it was open-label trial of a small patient population, so caveats certainly abound).

This is an urgent issue to understand better

On one hand, the data from these trials suggests that Afib ablation for our sickest patients should be the standard of care.

This is supported by subgroup analysis from other trials which has found that the benefit of ablation is most likely to be found in patients with symptomatic heart failure.

But on the other hand, this data is too good to be true and needs to be replicated before we widely implement this practice.

We need to be cautious before over-extrapolating small trials to have major influence on clinical practice for such a common condition.

We should also be mindful that the patients in these trials are not the same as most patients who have Afib.

When someone’s risk of death is very high, the bar to tolerate procedural risk that might change the trajectory is much lower than for the average patients.

When a patient is doing well, it’s very hard to justify we take procedural risks when a life-saving benefit has only been shown in advanced heart failure rather than in all-comers with the condition.

So I take the CASTLE trials to be profoundly important, but also to be in desperate need of replicating in a larger patient population.

And the question I posed at the top remains unanswered: does Afib ablation save lives?

I don’t really know, but it might.