Preventative stenting for high risk patients

When it seems to good to be true, it probably is

One of the hardest parts about heart disease is that you can’t predict who is going to have a heart attack with much precision.

A lot of attention in cardiovascular research has been focused on the concept of something called a “vulnerable plaque” which is an area of heart disease that looks high risk based on imaging.1

There’s a theory that if you can figure out with noninvasive testing that a patient is at high risk for a heart attack based on the presence of high risk features of their arteries that you might be able to prevent heart attacks with preventative stenting.

The PREVENT trial, just presented at ACC and published in the Lancet, tried to answer this question:

Can you put in stents for high risk patients as a preventative measure to reduce their risk of heart attacks in the future?

The PREVENT trial did something that’s kind of crazy - they put stents in people who weren’t have heart attacks and didn’t have severe blockages in their arteries

This is a pretty radical concept.

Stents are amazing advances - they clearly improve outcomes in patients who are having heart attacks and are often the most effective way to reduce symptoms of chest pain in patients with chronic angina.

But ask any cardiologist (or any doctor for that matter) and you’ll hear that we often put in too many stents in patients who don’t benefit.2

And so I looked at the PREVENT trial as the single presentation at ACC that I was most intrigued by.

Patient who have high risk imaging findings represent a scary group - they often haven’t had a heart attack yet, but based on their risk factors and imaging it can feel like they are a ticking time bomb.

PREVENT enrolled this patients in an open label, randomized trial where they were assigned to get stents or just medical treatment.3

The findings were pretty shocking - preventive stents seemed like they worked

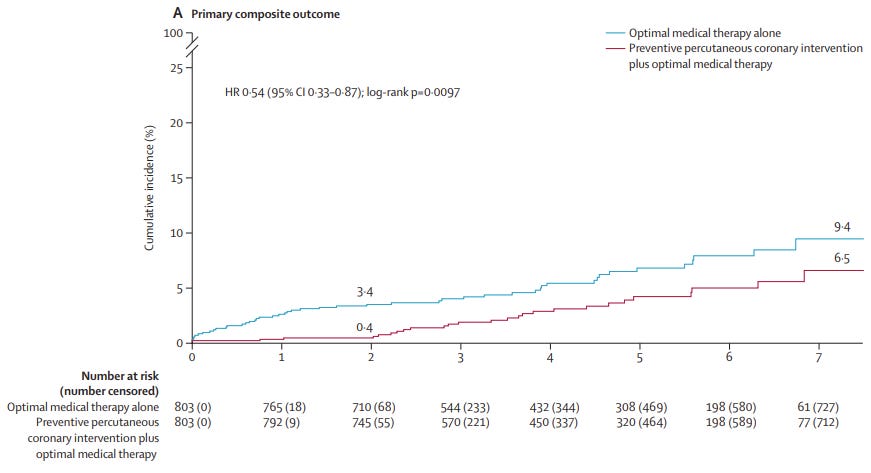

When you look at the top line data, putting in the preventative stents lowered the risk of bad things happening over the first two years of the study:

It’s interesting to note a couple of things about the results:

The overall numbers of bad outcomes are pretty low - even in the high risk patients, more than 90% do fine regardless of whether they go for a procedure or not

The composite outcome that they used included death from cardiac causes, heart attack in the vessel with the high risk imaging, need for stents to be put in, or hospitalization for progressive chest pain

The risk reduction happens early and then the curves don’t continue to separate over time

Risk reduction is driven mostly by the need for putting in more stents

There wasn’t really a difference in heart attacks or death

If you’re looking at that 4th bullet point - risk reduction was driven mostly by a reduction in need for more stents - and wondering if there’s something insane and circular about the rationale there, you aren’t wrong.

It’s pretty strange to say that if we put stents in you, we will reduce your risk of having stents put in moving forward.

And so I struggle with a composite outcome like this and truly thinking of this as a major advance.4

If you tell a patient that going for an invasive procedure now will slightly lower their chance of needing an invasive procedure in the future, but it doesn’t guarantee they will live longer, have less heart attacks, or truly need the procedure in the future, most people would opt against sticking catheters inside their hearts.

A good rule of thumb is that if something seems too good to be true, then it probably is

It would be so nice if a study like this worked - you can prevent heart attacks by doing procedures that are fun and lucrative for interventional cardiologists.

But when actually looking at the data, I think we’re pretty far away from this being practice changing.

I look at a study like this and I’m reminded of how little we know and how bad our prediction tools are.

After all, these are patients with high risk, vulnerable plaques. If you found this on a CT scan, the radiologist would need to have a conversation with you about the high risk nature of the finding to make sure that information wasn’t lost in the shuffle.

But the most pessimistic look at the data says that less than 10% of them will die, have heart attacks, or need invasive cardiac procedures over 7 years.

Our prediction models aren’t bad, but they certainly aren’t great. And they’re nowhere near ready for us to put in preventative stents based on the findings.

There’s a school of thought that maybe we shouldn’t be focused on just the high risk imaging findings as the target of therapy but as more of a marker of a patient who is at elevated risk - this is the concept of the vulnerable plaque versus the vulnerable patient.

I think that this makes sense, as long as we use that information as a target for medical therapy rather than invasive therapy.

Medical treatment works really well if we use it in the right patients.

And based on what we know now, there isn’t much of a role in having a stent placed if you aren’t having a heart attack and aren’t having symptoms related to the blockage.

A non-comprehensive set of high risk findings on imaging include things like large burden of plaque, thin cap fibroatheroma, spotty calcification, a napkin ring sign, and positive remodeling.

It’s pretty unlikely a stent has a life saving benefit in stable heart disease (meaning people who are not actually having a heart attack) and if you aren’t having symptoms then a stent can’t make you have less than zero symptoms.

These were patients clearly in need of medical treatment - they had elevated lipid numbers, 2/3 had high blood pressure, about 1 in 5 smoked, and a third had diabetes.

A couple of other points about this study. It was open label and not blinded, which can influence an outcome that is subject to symptoms, like the need for procedures. It was also a pretty small study - only a few hundred patients - so it’s hard to generalize to a large group. It’s possible studying a bigger group of people would make the results more impressive, but also possible it would make them less impressive.