The annual American College of Cardiology (ACC) is just finishing up its annual conference in Atlanta.

It’s fascinating to see how the powers that be in cardiovascular disease have started to make theater a huge part of the process of new scientific discoveries - the release of important trials in cardiology are increasingly clustered and presented during these national meetings.

ACC tends to the biggest annual event in cardiology, where a lot of important trials are unveiled to the world.

It can feel like it’s hard to keep up with the medical literature even during slow times, so a huge bolus of new papers with each ACC Conference is a particularly overwhelming time.

I’m planning to go through some of the most important ones in this newsletter partly because I’m interested in disseminating the information, but partly because I selfishly want to force myself to really dig into the new papers and this provides an outlet.

We’ll start today with something that is almost canonical in cardiovascular disease - the use of beta blockers after someone has a heart attack.

Putting someone on a beta blocker after a heart attack is considered the standard of care

Basically every single cardiologist or internist will make sure that patients are on beta blockers after a heart attack.

Beta blockers are common medications like metoprolol (Toprol and Lopressor), carvedilol (Coreg), propranolol, atenolol, or anything else that ends in “-olol.”

They slow down the heart rate, reduce blood pressure, and lower the chance of dangerous irregular heartbeats because of the way that they block the impact of adrenaline on the heart.1

But the trials that showed a benefit in these patients were all conducted in a different era - and the way that we treat heart attacks has been revolutionized since that time, both medically and procedurally.

We have made tremendous advances in stent technology and placement. We have better blood thinners, antihypertensive treatments, and lipid lowering medications. We have operationalized heart attack triage in a way that gets people their lifesaving procedures more quickly and preserves more heart muscle.

And so a trial like this gets at the old medical adage that “half of what you learn in medical school will be wrong in 20 years, the problem is you don’t know which half.”

It takes courage for the investigators of this new trial to consider challenging the widely held belief that beta blockers are life saving after every heart attack, even in low risk patients.

The REDUCE-AMI trial studied beta blockers in patients who had heart attacks but didn’t have a ton of heart damage

The REDUCE-AMI studied patients who came in with a STEMI (a specific type of heart attack) who had a preserved ejection fraction after getting a coronary angiogram (the procedure during which a stent is placed).

This is an important distinction - these patients had preserved heart function.

Patients with significant cardiac damage weren’t included, and that makes sense given how strong the data is for patients with reduced ejection fractions to be on beta blockers.

The patients were randomized to beta blocker treatment versus placebo. Both groups had similar treatment with other cardiac medications, like blood thinners, ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and calcium channel blockers.

The beta blocker patients were preferentially given metoprolol and bisoprolol, two beta blockers that have very strong evidence behind them in heart failure.2

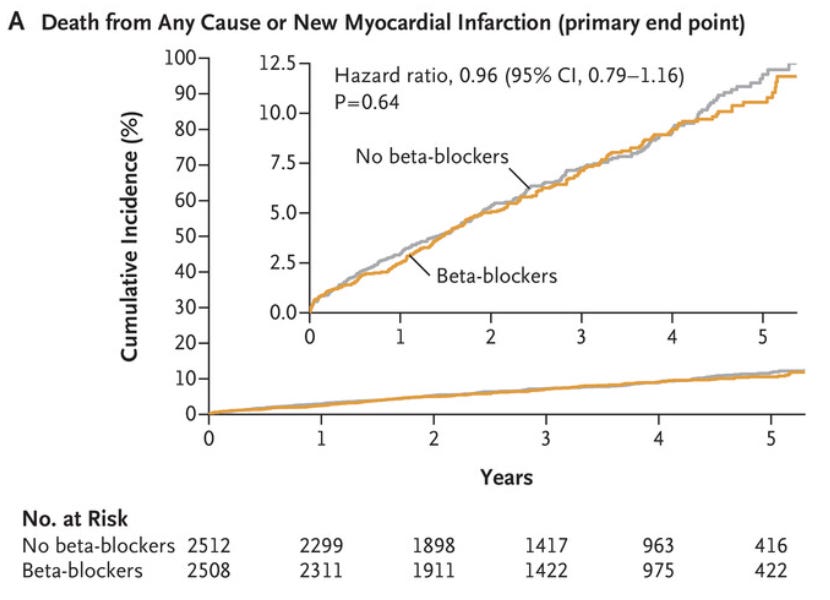

The results of the trial are pretty neutral - beta blockers don’t seem to reduce the risk of death or another heart attack in this group:

My first takeaway - patients who aren’t that sick aren’t that sick

Not all heart attacks are created equal. A heart attack that leaves you with a normal ejection fraction is different than one that leaves you with a low ejection fraction.

The better someone is doing, the less you need to do for them.

A patient who leaves the hospital after a heart attack with a normal ejection fraction is way less sick than a patient who leaves with a drop in their ejection fraction.

Making a distinction between how at-risk people are is one of the most important parts of medicine and this trial is further proof of that.

I think that one important message is that a heart attack that’s treated with a prompt trip to the cath lab and that ends up with minimal damage portends a good prognosis.

Low risk post heart attack patients don’t absolutely need to be on a beta blocker, even though many of them still will be on one.

After all, I still think it’s reasonable to put someone on a beta blocker if they’re having a lot of irregular heartbeats or if they have a comorbid condition like atrial fibrillation that also merits a beta blocker.

Using a beta blocker on a heart attack patient with a normal ejection fraction who still has elevated blood pressure also makes sense.

Don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater, just because a trial like this is neutral doesn’t mean that the drug has no role in these patients.

After all, there wasn’t a signal for harm, just no signal for benefit.

Another takeaway from this trial - results like this should make you wonder about the measurement of quality in healthcare

I’ve written before about how hard it is to measure quality in healthcare, but this provides a pretty striking example of how hard it is to assess the quality of a doctor.

Beta blocker use after a heart attack is quality measure that’s captured by lots of health systems and even the federal government.

And now we have a trial that shows for a subset of these patients that the treatment you’re using as a metric of quality doesn’t make a difference in the lives of those patients.

This isn’t a Goodhart’s law situation where we were just throwing patients on beta blockers because of a nonsense metric.

But incentives matter on the margins and when you’re using a metric to measure the quality of a doctor or heath system, you want to be pretty sure that it’s actually an important thing to be measuring.

Different beta blockers have different levels of emphasis on different areas of the body. A drug like metoprolol is considered to be cardioselective because of how much of its action is directed at the heart. But the truth is a bit more complicated, and even cardioselective beta blockers have impacts on other tissues in the body.

They didn’t preferentially use carvedilol, which is my favorite beta blocker. I’m not surprised - carvedilol is used with twice daily dosing and tends to lower blood pressure more than bisoprolol and metoprolol. But given that there’s a school of thought that carvedilol is a better drug than metoprolol (partly based on the COMET trial, which has its own flaws), it would have been nice to see it included.