If you’re like me, you’ve heard about the alleged harms of microplastics over the past handful of years.

Every once in a while, a mainstream press source covers the impact that microplastics are having on our health.

I’ve seen concern raised about the negative health impact of microplastics on fertility, neurodevelopment, and even cancer.

But if you’re not deep into this stuff, it can all feel a bit amorphous - is exposure to plastic *really* all that harmful?

Aren’t a million other things happening with our environments and our bodies that are also plausible contributors to some of these trends?

And in practice - do I really need to change out all of the plastic in my life for other materials?

The answer to that last question - do I really need to change anything? - is ultimately what matters to most of us. Removing microplastic exposure from our lives is ultimately more expensive and less convenient, and if we’re going to make our lives more difficult, shouldn’t there be some really compelling evidence that it’s worth it?1

A recent study in the New England Journal of Medicine is the most useful piece of information that I’ve seen to date as part of a look into how microplastics may be impacting our health.

This new study is the best assessment to date on the potential link between microplastics and cardiovascular disease

As I’m sure you’ve read from be before, more people die from cardiovascular disease than any other cause.

If microplastics are going to be hugely harmful to us on an order of magnitude that really matters, it makes sense that looking at a common disease would be a good place to try to find a link.

This new study took a really interesting approach to try to understand how microplastics impact heart disease - they studied patients who were referred for surgery to remove a severe blockage in their carotid arteries and looked at crap that actually came out of their plaques.

When you look under a microscope, you could see that more than half of them had actual microplastics stuck in the plaque in their arteries:

And it’s interesting to see that the people who had microplastics in their arteries weren’t sicker by traditional metrics than people who didn’t have the microplastics in their arteries - rates of high blood pressure, diabetes, and smoking were similar across the groups.

The people who had microplastics in their arteries had higher levels of multiple different inflammatory markers, all of which have been linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular events.

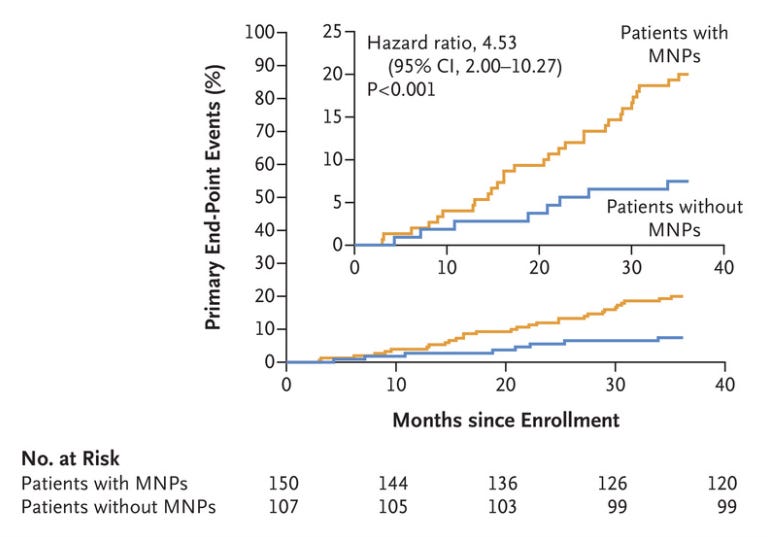

But most importantly, the risk of further cardiovascular problems moving forward was much higher in the microplastic group:

The Kaplan-Meier curve shows the risk of stroke, heart attack, or death was over 4.5-fold higher in the microplastic group than in the group without microplastics in their artery plaques.

That’s a pretty big difference! And it’s certainly an alarming piece of information to think about.

What conclusions can we draw from this study?

The honest answer is: I’m not really sure!

On one hand, the 4.5-fold increased risk of heart attack, stroke, or death in the group with microplastics in their arteries is a pretty compelling increase in risk.

But we don’t really know what drives that risk.

We also don’t know whether the groups differed in their exposure to plastics.

It’s equally plausible to me that there’s a biological difference between people in how their bodies take in or absorb plastic particles that we are exposed to.

Maybe it’s not that the microplastic group used more plastic in their day-to-day lives - maybe there’s something else about their physiology that makes them incorporate microplastic particles into their arterial plaques.

We have no idea what’s the chicken and what’s the egg here. Which came first, the inflammation or the microplastics?

Perhaps even more importantly, we don’t know what we don’t know here.

We don’t know why people get microplastics in their arteries. We don’t know whether there are differences in plastic absorption between different groups of people. We don’t now whether their behaviors are different, whether one group exercises more, whether they come from different socioeconomic levels, or anything of the other countless confounding variables that could change the nature of this discussion.

And so before you get ready to draw a definitive conclusion, keep in mind that there’s less that we know than that we don’t.

I disagree pretty strongly with the editorial accompanying the study

It’s worth reading the accompanying editorial to the paper in full:

On one hand, there’s a pretty compelling and simple argument here:

People with microplastics in their arteries have worse outcomes than people who don’t have them, even though they don’t *seem* sicker by traditional metrics.

And multiple large, professional societies that have looked at the data agree that plastics are present in many tissues of the body and that plastics endanger human health at every phase of the plastic life cycle.

But I struggle with this editorial for a couple of reasons.

First, as I mentioned above, this isn’t really the type of study that let’s you draw a conclusion about causation - it’s an association study, not an intervention study.

As I’ve discussed before, you can’t use the transitive property to conclude about the benefits or harms of something. It’s not good enough to say that an association + a plausible biological mechanism = evidence of causation.

Second, the editorial goes on to make very large conclusions that have far reaching implications on the role of a physician as an advocate/activist:

Although there is much we still do not know about the hazards to health and the environment posed by plastics, the information now available is cause for concern. Current patterns of production, use, and disposal are not sustainable.9 In response to the growing problem of pollution from plastics and production of plastics, the United Nations has resolved to develop a Global Plastics Treaty, and negotiations are under way.10

What can physicians and other health professionals do? The first step is to recognize that the low cost and convenience of plastics are deceptive and that, in fact, they mask great harms, such as the potential contribution by plastics to outcomes associated with atherosclerotic plaque. We need to encourage our patients to reduce their use of plastics, especially unnecessary single-use items. We need to inventory our own and our institutions’ use of plastics and identify areas for reduction. We need to express our strong support for the United Nations Global Plastics Treaty. We need to argue for inclusion in the treaty of a mandatory global cap on plastic production, with targets and timetables, restrictions on single-use plastics, and comprehensive regulation of plastic chemicals.

I’m not sure that telling my patients to reduce their single use plastics is part of my job.

I’m also not sure it’s a physician’s job to be an expert on the sustainability of plastics and the pollution-related externalities associated with their production.

We have enough important things to cover during our appointments with patients - we can’t take every preliminary association and use it as a jumping off point to draw conclusions that fit with our environmental priorities.

By all means, it’s reasonable for a doctor to have an opinion about the policies that our society should implement regarding plastic use.

But I don’t think it’s reasonable to start making that part of my conversations with patients based on this level of data.

Every second I spend talking about plastic is a second I don’t spend on the things that I have a higher level of confidence really move the needle here.

If I’m talking about polyvinyl chloride instead of hypertension, I think that means I’ve lost the plot.

If you prioritize everything it means that you prioritize nothing.

And so this stuff isn’t going to be something that I bring up with my patients until I have more confidence that I understand the issues at play.

What I’m doing in my own life - exercising the precautionary principle

I’ve spent basically this whole newsletter telling you that I don’t find this data compelling enough to incorporate into my medical practice and that I disagree that physicians have an obligation to discuss these topics with our patients.

So I wouldn’t be surprised if the message you’re getting is that I don’t think microplastics are a big deal.

But that’s not really how I am approaching this issue for myself.

I’m alarmed by the data presented in this paper, just like I’m alarmed at the potential impact of these microplastics on our neurodevelopment and fertility.

There’s a difference between believing data to be plausible and having a high level of confidence that there’s causation.

In my own life, I’ve stopped using a plastic water bottle at work and I’ve swapped out much of my plastic food storage containers for glass. I won’t reheat anything in plastic, and I try to avoid exposure as much as I can.

I think the precautionary principle makes sense here - taking action doesn’t cost much, and there’s a chance it might help.

One other quick point - I am not sure what proportion of our microplastic exposure is ambient versus individual. Are there so many microplastics in our water and our food that we can’t avoid it even if we try?

And so while I’ll make these decisions for myself, I’m not sure how meaningful they really are in terms of actually impacting my health (or my family’s health) moving forward.

This isn’t an article on environmental harm, climate change, or fossil fuels. I’m not well versed enough in that side of things to have anything useful to add. Let’s stick to an angle I can discuss that might be useful to someone reading this: the medical side of things