Almost everybody is going to get heart disease at some point in their lives.

That may sound hyperbolic, but it’s actually just being literal. Even if you don’t die from heart disease, chances are you will die with heart disease.

That’s why understanding how to evaluate, risk stratify, and treat is so important for all of us.

Last week, I wrote about a CT scan technology that holds the promise of potentially making stress testing obsolete.

Today’s newsletter is going to be a little bit cynical and even maybe a little bit exaggerated (I’m not even sure I 100% believe everything here), but I think it’s worthwhile to consider as a thought experiment.

I’ve certainly ordered a lot of stress tests for my patients that I don’t actually think have led to any improvement in either the quality or length of their lives. I strongly suspect that I’m not alone here - many doctors are guilty of this useless testing

A critical appraisal of how are using these tests, and more importantly, why we are using them is important as we evaluate our practice patterns and the way that we take care of patients.

If you’re a non-physician who is reading this, perhaps this will empower you to ask your doctor the question of why before you’re set for a stress test that may or may not change how you’re actually taken care of.

Remember, stress tests don’t directly look at your arteries, they use a surrogate marker to infer information about blood flow

As I wrote last week, stress tests evaluate whether there any severe blockages in the arteries around your heart.

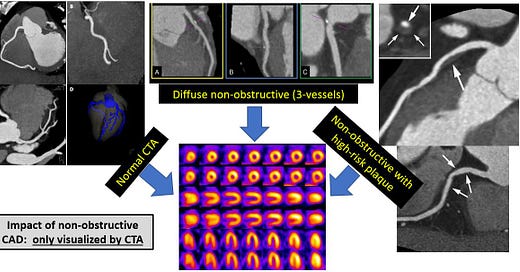

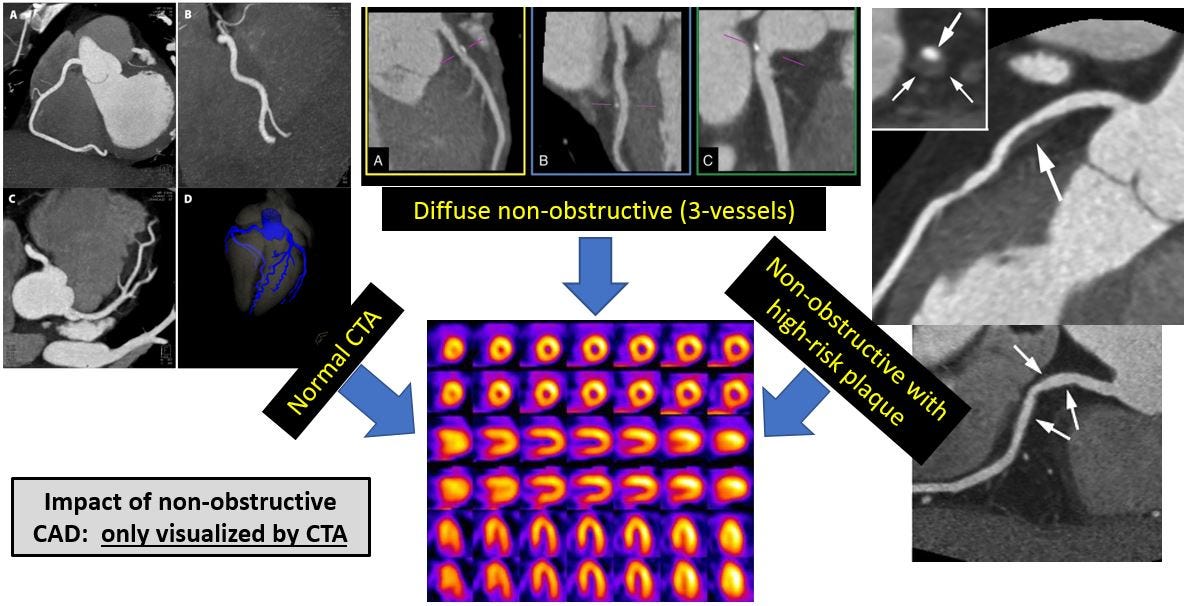

They don’t tell you anything about non-severe blockages, and they generally require some type of anatomical testing to fully understand the location of a blockages, how severe they actually are, and whether they even exist:

But ultimately, most stress testing is trying to determine whether someone has coronary artery disease and how severe it is.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the medical term for what we colloquially call heart disease. This isn’t actually disease of the heart, but rather disease of the blood vessels around the heart.

If you have to blockages in these arteries, it’s possible and even probable that you have disease in other blood vessels. Heart disease is a systemic disease of the arteries.

You may have heard the terms atherosclerosis, arteriosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries. They all mean the same thing. The medical term that’s favored now is the acronym ASCVD, which stands for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

We’ll use these terms interchangeably, but you should know that they all mean the same thing.

Most people who have heart disease have stable heart disease. This is an important medical distinction

Stable means different things to medical and non-medical audiences.

In this context, stable heart disease means that a patient has not had a recent heart attack and does not have a progressive chest pain syndrome.

If somebody has a recent change in the pattern of symptoms that they are experiencing, that’s not a stable syndrome, and it’s not reflective of stable coronary artery disease. Ditto if someone had a recent heart attack.

The distinction between stable and unstable heart disease is really important. It sounds so simple, but it’s major split in how we manage patients.

Clinical trials looking at stable heart disease exclude people with unstable heart disease from being enrolled, and vice versa. Understanding who the patients in the trial are helps you understand whether the results of that trial are applicable to the patient in front of you.

And so I think it’s vital to note that stable disease isn’t the same as unstable disease - when someone has a heart attack, or progressive chest pain syndrome, their biology is different than someone who hasn’t.

What we’re talking about here is stable heart disease and the way we test and treat these patients.

Noninvasive tests help figure out if people have heart disease. But the reaction to abnormal tests often goes down a road that doesn’t make people feel better or live longer

The problem here isn’t with the stress tests themselves.

The problem is with the way that we react to these tests and the way that these reactions often lead to unnecessary treatments.

Most doctors who see an abnormal stress test send a patient for a coronary angiogram, a procedure where we stick catheter in your heart and take pictures of the coronary arteries.

Once you go for an angiogram, if there any severe blockages, it’s really, really hard not to put in a stent to open up those blockages.

After all, you had enough symptoms that you ended up getting stress test, that stress test was abnormal, and now you’re sedated on a procedure table with a severe blockage.

Putting in a stent is fun, easy to do, might make you feel better, and is very lucrative for the treating physician.

There’s just one problem - the evidence to support putting stents in people with stable heart disease just isn’t that strong.

You learn a lot from looking at the clinical trials in stable heart disease

The COURAGE trial is one of the most important trials looking at whether putting stents in patients with stable heart disease improves their lives.

Look at the curves from COURAGE, it’s pretty clear that an invasive approach isn’t a magic bullet compared to medical treatment:

COURAGE found no benefit in survival or heart attack prevention, but there was a slightly faster improvement in reducing chest pain by putting stents in (but even that benefit went away after a couple of years of medical treatment).

It doesn’t stop with COURAGE. Consider the ISCHEMIA trial. ISCHEMIA asked a provocative question - do the patients with the absolute most abnormal stress tests benefit from going right for stents rather than waiting until symptoms develop before taking an invasive approach?

ISCHEMIA took patients who had the type of stress tests that usually send patients directly to the emergency room and then sent them all for CTAs to rule out disease that requires bypass surgery and make sure that they actually had severe heart disease.

In the real world, almost every patient enrolled in the ISCHEMIA trial would have been sent to the cath lab just on the basis of their stress tests - you needed a very abnormal stress test to be enrolled in this study.

But here’s the problem that ISCHEMIA showed us: it’s not clear that routinely putting stents in these patients makes much difference, especially over the short term:

ISCHEMIA showed a small reduction in heart attacks that took a few years to show up. There was no benefit in survival and there was upfront risk with doing the invasive approach.

How do you look at the ISCHEMIA trial is a Rorschach test for how do you think about the value of putting in stents.

On one hand, you can look at death or even death from cardiac causes, and see that there’s no benefit in going right for a stent. On the other hand, long-term, there does seem to be a small long term reduction in heart attacks (but no reduction in death) from the group that had an angiogram done upfront.

The most generous read of the clinical trials in stable heart disease is that by being aggressive with our therapies, we might be able to prevent heart attacks down the road for the highest risk patients.

The most cynical read of the clinical trials in stable heart disease is that we waste a lot of money and subject patients to a lot of procedures that have no impact on the quality or length of their lives.

One last complexity - getting a stent for stable heart disease may not even make you feel better compared to pretending to put a stent in

If you haven’t heard about the ORBITA trial, it’s worth knowing about, even if you don’t dissect it in depth.

ORBITA is the only trial that I’m aware of that compared putting a stent in to pretending to put a stent in.

This trial took patients who had symptoms related to a blockage, put stents in half and pretended to put stents in half and then followed them for 6 weeks while adjusting their medications.

There was no difference between the two groups, which suggests that some degree of benefit from stents may be the placebo effect.

And when you couple ORBITA with ISCHEMIA, COURAGE, and a lot of other data, you end up with headlines like this one from the New York Times:

Let’s get to the point and wrap this thing up

If putting stents in people with the absolute most abnormal stress test doesn’t save lives and pretending to put in stents may help with symptoms, it’s not hard to keep going down the logical path to the point where a stress test becomes completely superfluous.

After all, if you can’t make a diagnosis of heart disease with a stress test and you need an anatomical test to confirm, why don’t you just do the anatomical test?

If acting on the most abnormal stress tests doesn’t improve someone’s life for years (and never makes them live longer), what was the point of the stress test in the first place?

It’s not that much of a leap to make the argument that a stress test is often useless.

Maybe we should just take patients who are suspected to have heart disease for a coronary CTA to diagnose whether or not they truly do and exclude incredibly high risk disease that might benefit from bypass surgery.

Then you can medically manage these patients, and only send them for invasive procedures when they have symptoms.

As I said above, I’m not sure I believe all of this argument, but I certainly believe enough of it that you’re reading it here.

I’ve certainly been reevaluating my clinical practice in this realm, and if you or a loved one are sent for one of these tests, maybe it’s worth asking a few questions about where the cascade of testing is going to end up.

Disclaimer: This newsletter is for general informational purposes only. This is not medical advice, I’m not your doctor, and nothing that you read in this newsletter establishes a doctor-patient relationship.