The evolution of a nutrition agnostic

The most important book I’ve ever read was “Good Calories, Bad Calories.”

It’s a book by the acclaimed science writer Gary Taubes, whose NY Times Magazine piece, “What if it’s all Been a Big Fat Lie?” might have made its way onto your radar back in the early 2000s. This is the provocative article that got him the advance to write GCBC.

The crux of the book is questioning the conventional wisdom about carbs and fats, and accusing the mainstream nutritional establishment of getting it all wrong about saturated fat, obesity, sugar, and chronic disease.

Very few things that I’ve ever read have totally changed the way that I think, and this book certainly did.

I knew from the Omnivore’s Dilemma and Food Politics that a lot of the government advice and the Food Pyramid were based on political negotiations clouded by special interest lobbying, but I had no idea that basically none of our nutritional guidelines were based on high quality data.

Before GCBC, I had always naively assumed that major medical organizations like the American Heart Association would only release guidelines that were based on unimpeachable information.

Unfortunately, mainstream nutritional advice and professional society nutritional guidelines have never been based on particularly reliable information.

Reading this book was the first time I realized that medical guidelines were written by fallible people (super knowledgeable people with significant subject matter expertise, but still fallible ones), not omniscient beings.

It taught me to be critical of the medical literature in a way that I never was before.

The main point of “Good Calories, Bad Calories” is about the shoddy nature of nutritional research

I’ve written before about how hard it is to do a good nutrition experiment - we all have to eat, and it’s impossible to manipulate a single variable with an experiment.

If you eat less fat, you have to eat more of something else.

And if you study a group assigned to a low fat diet, you don’t know whether the outcome that you observe is related to the fact they ate less fat or the fact that they ate more of something else.

But most of the guidelines don’t come from actual experiments, they come from observational research based on crappy data.

Most nutritional studies - the kind of stuff you see on the Today Show about how coffee is killing you (or saving your life) or how broccoli prevents ovarian cancer - is based on data acquired through a food frequency questionnaire, which is totally useless because of how unreliable it is.

These questionnaires are where people fill out surveys about how frequently (and in what portion sizes) they eat certain foods, and then are either followed to see their health outcomes or they are simply asked about health problems.

This type of research has two major problems:

Because it is observational rather than experimental, it simply cannot prove cause and effect, so the conclusions you can draw are limited and littered with confounding

Relying on recall of what people ate is a notoriously unreliable way to collect accurate information, so the data you’re using to draw those conclusions may simply be wrong

But this book goes a bit farther than just critiquing the shoddy state of nutrition research

If you ask someone who has heard of Gary Taubes what his books are about, they’re going to tell you that he writes about how carbs are bad and saturated fat doesn’t cause heart disease.

A lot of the reason that many people believe meat causes heart disease comes from something called the “saturated fat → cholesterol → heart disease hypothesis:”

Populations that eat more saturated fat tend to have higher levels of heart disease

Saturated fat tends to raise LDL cholesterol levels

Higher levels of LDL increase risk of heart disease

Ergo, saturated fat increases the risk of heart disease

But what Taubes does so successfully in his book is make the argument that the epidemiology isn’t reliable and that the pathophysiology of heart disease is more complex, particularly with regards to insulin and insulin resistance.

Insulin resistance is a really big deal

After reading GCBC, I started wading into the world of low carb diets, where you quickly learn a lot about metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance.

If you’ve been reading this newsletter for a while, you’ve seen me write about this over and over again.

A lot of the time, a low fat diet (or a diet that tries to reduce saturated fat) ends up having a ton of carbohydrates and precipitating insulin resistance, prediabetes, and metabolic syndrome.

So part of the problem here is that following the standard recommendations - avoid “artery clogging saturated fat” - can lead you down the road of chronic disease.

And for a while after reading this book, I was fully persuaded that Taubes was right about everything - carbs make us fat and sick, sugar is toxic, and saturated fat should be exonerated.

Unfortunately, even though this makes for a compelling story, the theoretical biology doesn’t work out in the real world.

Not everyone loses weight on a low carb diet, and some people who lose a lot of weight still have heart attacks

If you really dig into the research here, you quickly find that it gets really complicated.

You can look at the meta-analyses, which don’t find that saturated fat matters.

Or you can look at the the Cochrane review, which suggests that it does.

Dealing with patients hasn’t exactly illuminated a clear path forward. I’ve had a chance to see patients who I would have expected do well on keto who actually put on weight. Some patients even lose weight when they start eating more carbs.

And I’ve seen every other single permutation you can think of.

There’s even a phenomenon that’s been termed “Lean Mass Hyper-Responders” that describes an incredibly high rise in LDL cholesterol levels when people go super low carb, which has been responsible for some of the highest LDL-C levels that I’ve ever seen.

The mainstream understanding of saturated fat - that it raises LDL cholesterol levels - is directionally accurate (although there’s a lot of person-to-person variability).

And I find it very hard to imagine that a diet that makes your LDL-cholesterol levels shoot up doesn’t increase the risk of heart disease.

When it comes to diet, there’s too much person to person variation to draw sweeping conclusions

People have incredibly variable responses in their bloodwork to dietary changes.

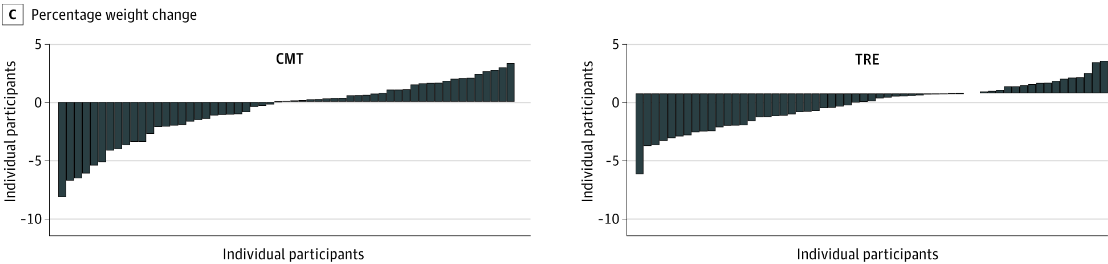

The TREAT study, a look at the effect of intermittent fasting on weight loss, provides the best graphic on the individual variability to a nutritional intervention that I’ve ever seen.

I think about this graphic frequently - it shows change in percent weight with intermittent fasting versus consistent meal timing across a study. Each bar is an individual person - just look at how much variability there is:

Some people gain weight, some people lost weight, and others have no change. And this isn’t even a study where they changed the nutritional content of the diet - they simply manipulated the time window of eating.

Different people are different.

It’s the only conclusion I can draw from my clinical experiences and the messy scientific literature here.

None of these discussions exist in a vacuum either

Most nutritional perspectives that you read about may start off scientific before venturing into the realm of belief and values.

After all, it’s hard to discuss these topics without conflating a lot of other charged discussions.

Is the keto diet bad for the planet?

Is it immoral to consume animals?

And you can’t forget the integral role that food plays in our culture - meals are part of how we celebrate our heritage, how we commemorate important milestones, and how we bond as human beings.

As you can imagine, a discussion of nutrition and health can very quickly move beyond just nutrition and health into very emotionally charged areas.

So what do I believe now?

I get asked questions by my heart disease patients about what they should be eating every single day.

They’re frequently surprised that I don’t tell them to cut out seed oils, avoid sugar like the plaque, or go totally plant based.

The more I learn about nutrition and heart disease, the less I feel like I know.

The further out you go, the deeper the water gets.

Based on my synthesis of the medical literature, my experience with patients, my own personal experience, and some extrapolation, here are a few conclusions that I think are right (but might not be correct when/if I revisit this topic in the future):

Calories matter and there’s nothing magic about eating low carbs and dropping insulin levels that suddenly makes the laws of thermodynamics moot.

Protein is important for optimizing muscle mass, which I think is one of the most under appreciated factors in aging well and avoiding chronic disease.

Carbs + fat without protein is a recipe for over-eating. Think about how easy it is to eat 4 servings of chips, donuts, cakes, cookies, or candy. There’s a reason that every single diet says don’t eat this crap.

Low carb diets work for some people because they restrict foods. They work for others because protein + fat can be satiating. Often when they fail it’s because of cheese, mayonnaise, or other low carb foods that are dense in calories.

Most of us know what junk food is and also know that we should avoid it. A lot of the questions about eating healthy are folks trying to find loopholes in this concept.

The last set of questions I get is around the people who feel great on a low carb diet but have a huge rise in their LDL-C numbers.

My take here is that you’re gambling with your cardiovascular health to live with crazy high numbers. I think it’s worth considering that a diet that optimizes for one thing (easy weight maintenance or energy levels) may not be optimal for something else (cardiovascular disease risk).

You might be fine, but you’re certainly gambling.

I recommend to patients that they have 3 choices here, only two of which I recommend: 1) do nothing; 2) change their diet; or 3) go on medications to lower their heart disease risk.

And so I’ll leave you with this: there’s a lot of uncertainty and a lot of individual variability.

When it comes to nutrition, the more confident and dogmatic someone is, the less deep their knowledge probably is (and it’s probably a tell that they haven’t worked with many patients).