Before we get started on today’s newsletter, I wanted to quickly share something cool that I’ve been working on with this audience: a podcast called “Beyond Journal Club” that’s a collaboration with the New England Journal of Medicine Group’s educational efforts.

The goal of the podcast is to look at important clinical trials and put them in context. We want to answer questions like:

Why was this study important? More importantly, why was it even done?

Where does it fit into the landscape of what we know about a disease and its treatment?

How does it change the way we take care of patients?

The impetus behind this is that most published research (even the stuff that’s well covered by the media) isn’t all that important or practice changing.

And many journal articles and the editorials that cover them are inside baseball written for a few world experts and not for the regular doctors like myself who take care of patients and want to apply data to use in the real world.

Our first episode is on the REVIVED trial, which asked the question: does putting stents save lives in patients with heart failure and severe heart disease?

It’s only 18 minutes long, and I think worth a listen if you find these newsletters interesting.

The cornerstone of almost every physician’s decision to prescribe someone medications to prevent illness hinges on assessment of risk.

Most professional guidelines recommend using validated risk calculators to evaluate cardiovascular risk when it comes to making decisions about treatment.

The higher the risk, the more benefit you theoretically have from prescribing medications to reduce that risk.

There’s an interesting new study looking at preventing heart disease in low risk patients with HIV that’s worth discussing, even if you don’t have HIV and even if you aren’t interested in HIV.

I actually think a study like this had broad applicability terms of how it informs our decision making about cardiac prevention.

People who have “low cardiac risk” can still have heart attacks

I see people every day who “never should have” had a heart attack or a stroke based on their risk calculators - but there’s a big problem with using these: they miss a lot of people who are at risk!

As many as 10% of heart attacks occur in people under 45 years old, and as many as half occur in people under 60.

The factor that most informs risk using these calculators is age - so younger people are the ones most likely to be missed in a risk assessment.

Let’s look at this study to see why it might be useful for us to know about.

This study looked at people with “low risk” who may be missed by the traditional risk calculators

The REPRIEVE study acknowledges that we don’t have great prevention strategies for people who don’t meet classic indications to go on medical therapy for heart disease.

Our risk assessments often miss a lot of things that can cause heart disease early - alarming family history, autoimmune diseases like lupus, chronic kidney disease, and chronic infectious diseases like HIV.

This study describes the knowledge gap we have here - no one knows if statin therapy reduces cardiac risk in patients with HIV, but we know that HIV raises risk and that this is a group that may be undertreated.

The study enrolled low risk patients: more than 3/4 of the patients had a 10 year risk of heart attack calculated at under 7.5% and half of them had a 10 year risk under 5%:

The patients also had well controlled HIV - high CD4 counts and low viral loads - which makes them similar to a lot of patients with elevated risk: well controlled and engaged in their health, but also vulnerable because of their biology.

They randomized patients to either pitavastatin (brand name Livalo) or placebo.

This is an interesting drug choice - pitavastatin is the statin with the lowest incidence of muscles aches and thus the least likely statin to be discontinued due to side effects. And, indeed, only 2.3% of people in the treatment group had muscle aches.

The REPRIEVE trial found that statin therapy reduced heart attack risk in low risk patients

The results here were surprising to me - I wouldn’t have expected it to be so easy to show a benefit in this population.

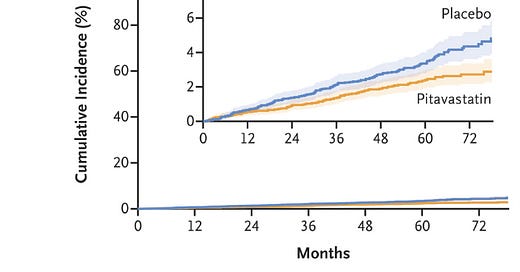

The event curves separated after about a year and continued separating throughout the duration of the study:

That’s pretty impressive risk reduction for a group that isn’t at super high risk.

It’s interesting that over the course of the study, the event rate wasn’t actually higher than expected among the placebo group.

Pitavastatin just worked at reducing cardiac events.

The authors report the numbers a bit oddly for translation to the real world - risk is described over 1000 person years rather than as percentages - but the message is the same.

This study will certainly change my prescribing habits - I am persuaded that patients with HIV should be on pitavastatin regardless of baseline cardiac risk, even if their HIV is well controlled.

Where this study becomes generalizable: Not all risk is the same

I often see risk assessments done based on absolute numbers.

In other words: does the likelihood that heart attack risk is reduced exceed the likelihood of developing a side effects of the drug?

This is often how my patients ask me about risk. I get asked very often, “what percent of people develop side effects?”

But I think that’s the wrong question and the wrong framing here.

The side effects of these drugs are easily measurable and reversible. In the case of statins, there’s a small risk of a rise in blood sugar and new onset diabetes and a small risk of muscle aches.

We certainly saw that risk present in this study:

But I can track blood sugar and we can watch out for muscle aches.

People don’t go from not having diabetes without a statin to having uncontrolled diabetes and going blind, developing renal failure, and requiring amputations when they start one.

The change is small - it’s an A1C going from 6.2 to 6.5 - and it’s able to be tracked and goes away when you stop the drug. Ditto for muscle aches - they go away when you stop the drug.

So the risks of these medications to me are small, measurable, and reversible.

But the risks of not going on these medications have a much wider array of possibilities

Let’s say you would have prevented a heart attack by going on a statin, but you didn’t, and so you had a heart attack.

Most likely, it’s no big deal. The majority of heart attacks can easily be treated with a stent and medications.

It’s a low probability that the heart attack is going to be life changing. After all, most heart attacks don’t lead to irreversible congestive heart failure or sudden cardiac death.

But that low probability event isn’t reversible the same way that a drug side effect is.

If you do have a huge clot in your left anterior descending artery, your life can be totally changed forever. Or if you have a cardiac arrest, there’s no promise that you’ll receive prompt CPR and have immediate neurologic recovery.

Risk in this way is asymmetric - the risk of not using the preventive medication is a downside risk that’s gigantic, irreversible, and can totally screw up your life forever.

The risk of a side effect of a drug is one that we very clearly know. It’s also a risk we can both track and reverse.

The point isn’t that everyone needs to take a statin today

The point is that risk is hard to measure and the future is impossible to predict.

Understanding whether there are variables that make your risk higher than would be reasonably estimated using traditional metrics is the way you take control of your health.

There’s nothing wrong with asking your doctor if there are any factors about your health that are missed with a standard risk calculator.

A patient with lupus is someone who I might treat a systolic blood pressure of 130. A patient with a strong family history might get an aspirin to prevent a first heart attack.

And a patient with HIV should probably be on a statin, at least if you find the REPRIEVE data persuasive (I certainly do!).