Why doesn't your doctor talk about diet and exercise?

Every single time I write something about prescription medications, I receive comments and questions about why doctors are always pushing pills instead of getting to the root cause of chronic disease.

In other words, why don’t we talk about diet and exercise instead?

The short answer is that a lot of doctors do talk about lifestyle medicine, but that discussion is insufficient for most patients.1

Today’s newsletter is about the physician perspective2 on why we often spend more time talking to you about prescription medications than about your exercise regimen.

Some people aren’t going to eat better or exercise regardless of what we say in the doctor’s visit

The data looking at adherence to lifestyle changes is not great.

And my clinical experience is that the data actually overstate how likely most people are stick with a diet and exercise program.3

Very commonly, I’ll have a conversation with a patient about elevated blood pressure where we discuss that the options are to make lifestyle adjustments or to go on medications.

After all, medical society clinical practice guidelines always recommend lifestyle modification as a first line treatment for elevated blood pressure.

But even after deciding that we are going to give diet and exercise a 3-6 month trial to see the impact on blood pressure, it’s far too common for patients to return at their next visit with explanations of why they haven’t been able to follow through on their intention to eat better and stay more active.

I am very much in favor of lifestyle changes to put chronic health conditions into remission, but it’s too easy to get into the trap of “let’s give it a few months” before we end up a few years later with longstanding and untreated high blood pressure or lipids.

After an attempt at lifestyle changes is unsuccessful, treating chronic conditions with pharmacologic interventions is the standard of care.

The discussion about exercise and diet is too often met with a list of objections

One of the first questions I ask patients when they come in for a preventive evaluation is “how active are you?”

The most common response to that question: “not as active as I should be.” That’s often followed with an explanation of why.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had a conversation about the importance of physical activity with a patient and all I hear back are objections about why that’s not possible.

Sometimes the objections are about not having time to work out, sometimes they are about chronic joint pain, sometimes they are about how hard it is to eat better.

One thing I can tell you with certainty is that no patient is ever surprised that I am talking with them about the importance of diet or physical activity as it pertains to their health.

People know that eating well and exercising are important.

So in some ways, the suggestion that we should be discussing these things in a doctor’s visit feels like a redundant exercise.

If my patients already know that they should be doing these things because of the impact on their health then why spend time reiterating the importance of healthy lifestyle habits that they are firmly aware of?

And why is the doctor’s appointment the place for objection-handling the obstacles to exercising more and eating better?4

We’re trained to assess readiness for decision-making, and some patients are barely at pre-contemplation

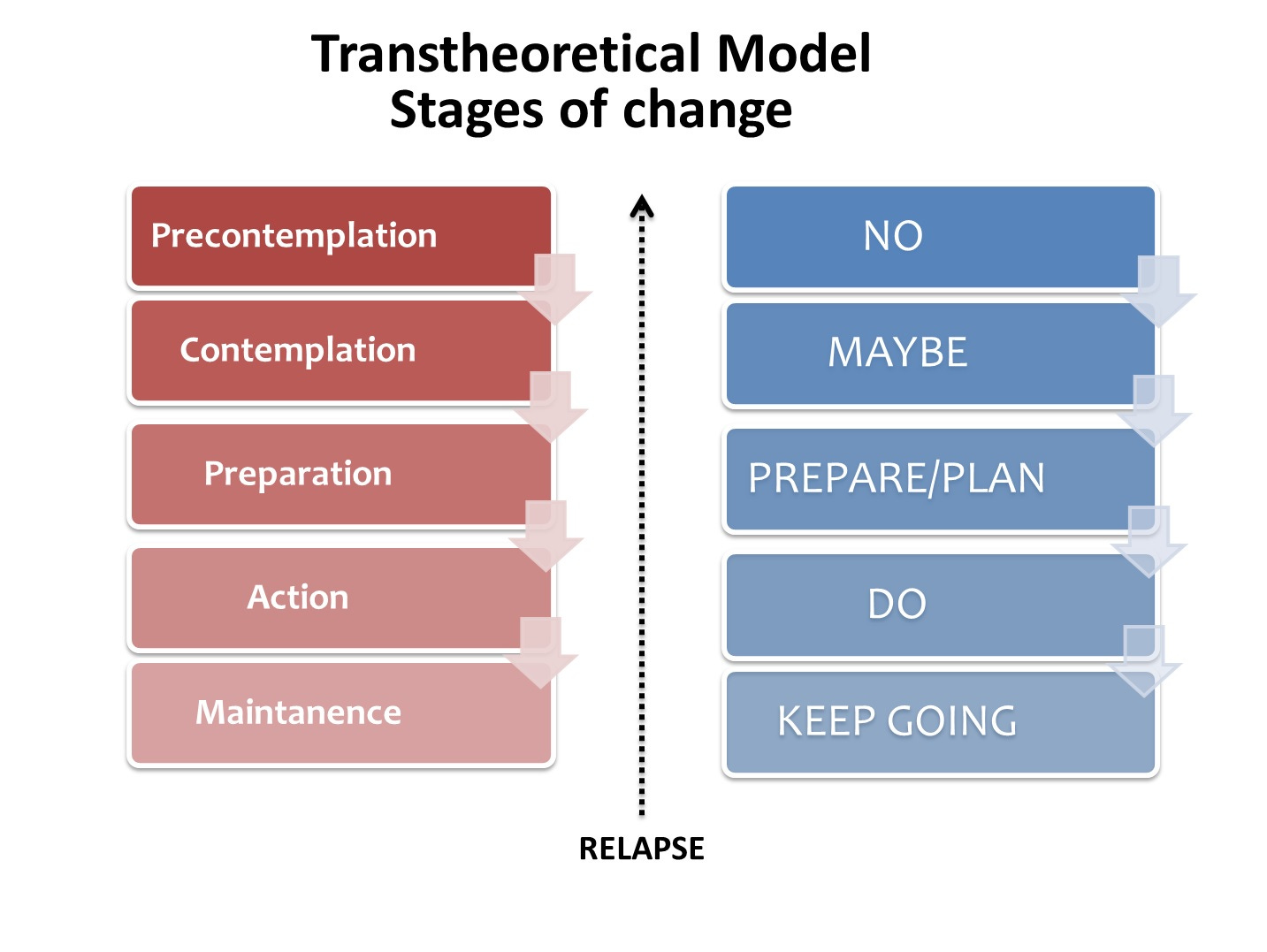

One of the things that you learn in medical school and during training is the about motivational interviewing and assessing someone’s readiness to change.

The transtheoretical model for the stages of change is one method of doing this assessment that I’ve found useful in counseling patients:

Most patients that I see are in the precontemplation phase of behavior change - they aren’t ready to make any real changes.5

Part of the assessment that we are making during a doctor’s appointment is where you are on the stages of change.

If a patient is precontemplative, a discussion of diet and exercise isn’t a high yield use of time during a doctor’s appointment.

It’s fairly common for me to ask a few questions to try to assess where someone is, and then decide that because they aren’t ready we are better off spending the time in the appointment discussing other things.

We’re supposed to get to the root cause of the problem, but the root cause is too much visceral fat and the associated insulin resistance and low grade inflammation

You’ll see a lot of alternative medicine practitioners criticizing the way that doctors only treat symptoms and never get to the “root cause” of chronic disease.

It’s a ridiculous criticism.

There’s no source more mainstream than the CDC, which clearly states that “many preventable chronic diseases are caused by a short list of risk behaviors: smoking, poor nutrition, physical inactivity, and excessive alcohol use:”

So the root cause of chronic disease is pretty clear - doctors know about it, patients know about it, and national medical organizations disseminate this information broadly.

Medications improve outcomes in people who don’t make lifestyle changes

I make most of my decisions based on data from randomized clinical trials.

In those trials, they don’t tell patients to avoid making lifestyle changes. But what you see in study after study is that appropriately treating high blood pressure, elevated lipids, and obesity with medications lowers the risk of heart attack, stroke, heart failure, and death.

So it’s not an either/or question. It’s both/and.

Medications are a tool, just like a treadmill, or a dumbbell, or a surgical intervention.

The value of a tool is in how you use it.

Doctors aren’t trained in nutrition or exercise and so if that’s what you’re looking for, you should see someone who has that expertise

One of the lines that I hear to criticize doctors all the time is about how little time we spend in medical school on nutrition.

You’ll see this style of doctor-critique on social media from every diet tribe.

And that’s true - doctors don’t get very much training in nutrition.6

And we get essentially zero training during medical school in exercise - but we do get taught about some observational data on how exercise is linked to better health outcomes.

Doctors are trained to evaluate symptoms and treat medical conditions with medications and procedures.

We are the only practitioners who are allowed to give you prescription drugs, send you for diagnostic testing, or perform invasive medical procedures.

You wouldn’t go to a nutritionist and ask about your blood pressure medications.7

You wouldn’t go to a personal trainer to ask if you need a stress test or a cardiac catheterization.

So why should a physician be the person who instructs people on diet and exercise apart from making the recommendation that those things need improvement?

If you’re looking for advice on the type of exercise to do, or how to eat better, then it’s probably better to see someone who is trained in those domains because your doctor almost certainly is not.

Once your doctor has identified the issue of chronic disease in need of treatment and suggested that diet changes and more exercise might lower your risk of cardiovascular disease and reduce your reliance on medications, isn’t that where we get to a discussion about the things a doctor can be most helpful in doing to treat those issues?

It’s not a good use of your time during most doctor visits to discuss your exercise regimen or your micronutrient intake - you should be going to an expert in those areas and spend the doctors visit making decisions about medications, testing, and procedures.

Plus - and this might be the most important thing - doctors are just as bad at lifestyle as patients!

Doctors are hypocrites just like all other people are.

Many of us don’t live the lifestyle that we would recommend that our patients live.

And so maybe the reason your doctor isn’t spending a ton of time trying to troubleshoot your exercise challenges or crappy diet is because they are struggling with the exact same things themselves.

I’m going to write about this topic - why doesn’t your doctor take better care of themself? - in detail next week, so let’s wrap this up.

There are a lot of reasons why going to the doctor doesn’t help people be healthy.

After all, we have a “sick care” system and not a “health care” system.

Diet and exercise are certainly two of the pillars of a healthy lifestyle. But lifestyle also includes things like sleep, stress management, amount of time sitting/sedentary (different than exercise!), social connections, smoking, etc.

The perspective - cynical and a bit jaded - is not one shared by all doctors, but I’ve heard pieces of this from enough of my colleagues that I think it’s fair to say that this piece does summarize a lot of different physician perspectives.

That’s because the data only looks at people who are trying a plan. Lots of patients never start anything and so would never be able to be included in any study on this stuff.

The counterpoint that I’ve heard is that doctors should be judged based on how we are able to inspire or persuade our patients to live healthier so that they ultimately need fewer rather than more medications. I firmly believe if a patient wants me to help troubleshoot their life, they will make that clear to me that is the type of help they are looking for. If they’re really looking for tactics, I am happy to help - but I can’t remember the last time that happened. For all of the other patients, I don’t think objection handling about exercise is a productive use of our limited time in an appointment.

In my experience, people are here for a handful of different reasons. Some people haven’t identified that there’s a problem in need of solving with lifestyle changes. Some people feel like the changes are too overwhelming. Some people don’t know where to start and so it doesn’t feel realistic.

But after seeing thousands of patients and asking many of them about what they eat and how active they are, I’m pretty convinced that you don’t need any training to identify big issues. After all, just look at how much regular soda, chips, cookies, cakes, and other baked goods are consumed regularly - it doesn’t take a deep expertise in nutrition to know that most of that stuff is bad for you.

I am of the belief that most nutritional certifications are fairly useless. My unpopular belief is that the people who know the most actionable information about nutrition for most people are actually high level bodybuilders, but that’s a discussion for a different newsletter.