You would think that a device marketed as a stroke reduction tool would have clear evidence that it actually reduces strokes.

But when it comes to the Watchman device, a cardiac implant that is done more than 10,000 times a year, the data is murky, at best.

Helping my patients prevent strokes is one of the major things that I focus on in my clinical practice.

I see a lot of patients for something called “secondary stroke prevention,” which means that they’ve already had a stroke and our job is to prevent another one.

I write about stroke prevention from the perspective of someone who thinks about this question every single day of my life and has taken care of many different types of patients with strokes.

And so when I talk about the Watchman device, a medical device marketed to cardiologists as a stroke prevention tool, and I say that I have no real sense about whether it actually prevents strokes, that isn’t a cavalier opinion.

My considered perspective is that there is genuine uncertainty about whether this medical device that is being implanted in patients across the country every single day with the goal of stroke prevention actually does what it’s supposed to do.

A recent trial looking at the impact of the Watchman device brings the evidence behind this device up for debate again, so let’s look into the details.

The Watchman device covers an area in the heart called the left atrial appendage

One of the most common reasons why people have strokes is because they have a blood clot form in the heart that can travel to the brain and cause a stroke.

The most common reason why people get a blood clot forming in their heart is because of an irregular heartbeat called atrial fibrillation (often called afib for short).1

This is the reason why patients with afib are often placed on blood thinners like Eliquis or Xarelto - to prevent blood clots from forming in the heart that can travel to the brain and cause a stroke.

When blood clots form in the heart because of afib, they most commonly form in a place called the left atrial appendage, which is a small ear-like structure in the back of the heart.2

The theory behind the Watchman device is that if you block off the left atrial appendage, you prevent a blood clot that forms in that area from traveling up to the brain and causing a stroke.

It’s a concept that makes sense mechanistically.

There’s also data to support closing the left atrial appendage during cardiac surgery - the LAAOS III trial showed that closing off the left atrial appendage during cardiac surgery performed for other reasons lowers the risk of stroke (with benefit continuing to accrue over years).3

But the Watchman aims to close the left atrial appendage percutaneously, which means through a catheter inserted into a blood vessel.

The fact that the Watchman is done through a catheter based procedure and then implanted inside the heart leads to two potential issues, apart from procedural risk:4

The risk of an incomplete closure of the left atrial appendage, which can create a nidus for blood clot forming behind the device and then potentially traveling to the heart

The risk of a foreign body in the heart leading to a formation of a blood clot on the device, which could then break off and travel to the brain5

And unfortunately, the data on the Watchman has been pretty underwhelming.

The first two trials on the Watchman that led to its approval did not have very impressive data

The initial two trials on the Watchman were PROTECT and PREVAIL.

Both of these studies compared the Watchman device to anticoagulation with Warfarin (also known as Coumadin), which is a blood thinner that has fallen out of favor for stroke prevention in afib.6

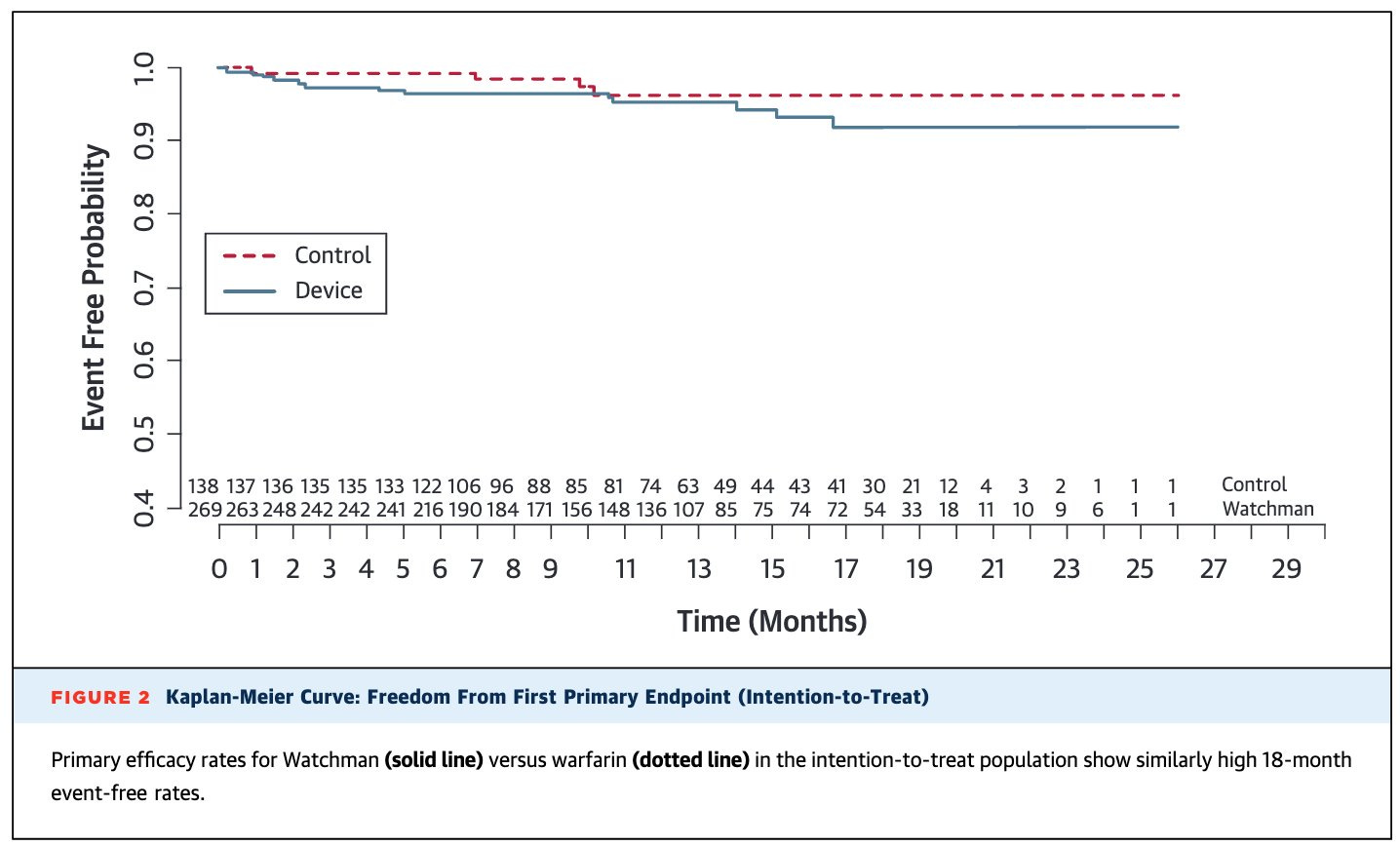

PROTECT found that ischemic stroke prevention was no better with the Watchman compared to Warfarin:

PROTECT also found that patients on Warfarin were more likely to have bleeding events, particularly bleeding inside the brain.

Incidentally, the benefit of less intracranial bleeding is a major reason why Warfarin has fallen out of favor, as Eliquis (an alternative blood thinner) seems to reduce that risk (which is why it’s likely better than Warfarin).

But you could reasonably look at PREVAIL and say that it suggests the Watchman is a reasonable option.

PREVAIL paints a much more concerning picture. In PREVAIL, the Watchman was inferior to treatment with Warfarin:

But the authors did an analysis to exclude events over the first 7 days after the procedure to conclude it was actually ok.

When you read the conclusion in the abstract, it’s kind of unbelievable they were allowed to publish this paragraph, which spins a negative results into a neutral one (and thus establishes the Watchman as a reasonable choice despite a negative result from this trial):

In this trial, LAA occlusion was noninferior to warfarin for ischemic stroke prevention or SE >7 days’ post-procedure. Although noninferiority was not achieved for overall efficacy, event rates were low and numerically comparable in both arms. Procedural safety has significantly improved. This trial provides additional data that LAA occlusion is a reasonable alternative to warfarin therapy for stroke prevention in patients with NVAF who do not have an absolute contraindication to short-term warfarin therapy.

And now we have OPTION, just published looking at the Watchman device

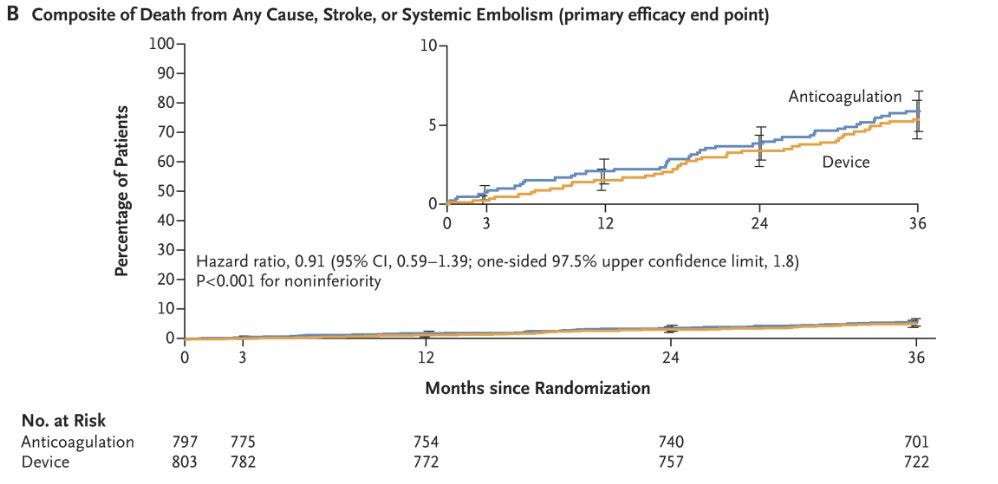

The OPTION trial studied patients going for ablation for atrial fibrillation.

They randomized patients to ablation + anticoagulation compared to ablation + Watchman device and followed them for 3 years.

Unsurprisingly, the authors found that being on a blood thinner increased the risk of bleeding.

But reassuringly, they found that the Watchman device and often stopping a blood thinner was not worse with regards to stroke than staying on a blood thinner:

And so, taken with the prior data from PROTECT and PREVAIL, I think most people will conclude that the Watchman is a reasonable alternative to being on a blood thinner.

After all, a lot of people do not want to take blood thinners - there’s easy bruising and risk of a serious bleeding complication.

People on blood thinners often don’t do things that they want in their lives - skiing being a particular concern with many of my patients.

As a result, if the Watchman is truly a good alternative to blood thinners in afib, then the OPTION trial is a really big deal.

Unfortunately, the devil is in the details and I don’t think OPTION is the last word

There are a few nuances that we should consider before we just take the top line result of OPTION at face value.

The stroke rate in this trial was really low - lower than you would expect based on the population studied. That suggests a healthier population than a real world cohort. And when you’re studying a higher risk population, you can’t just extrapolate the results blindly

20% of patients had leak from their device. As I mentioned above, this has real implications when you are deciding on stopping a blood thinner on someone

The other, and perhaps most important, caveat, is that the Watchman device only addresses one mechanism of stroke - a blood clot in the left atrial appendage that travels to the brain.

But not every stroke in patients with Afib originates in the left atrial appendage.

A medication works everywhere but a procedure only works in one place.

One major concern of mine is that the Watchman only addresses one thing but doesn’t impact all the other competing risks.

The second is that the Watchman introduces procedural and device related risk that it unpredictable when you’re deciding whether to place one.

If you could guarantee that the Watchman gets implanted perfectly, never develops a blood clot on it, and doesn’t have a leak after implantation, then it probably fits into an “all of the above” approach to stroke prevention.

But in the real world, where I don’t have the ability to know whether my patient is going to have a perfect device placement or a device related clot, I’m left with no real confidence that I’m making things better by referring them for a Watchman.

And so I don’t think we can consider this a true “alternative” to blood thinners in patients with afib.

But as the procedure gets better, and more personalized,7 there may be a role for it as part of a comprehensive stroke prevention strategy.8

I’m not fully ready to toss the Watchman aside, but I don’t find the data that we have - including OPTION - compelling enough to make me start sending my patients for it.

You’re going to be seeing the Watchman more and more because there’s now a combined billing code for ablation + Watchman

CMS recently finalized a new billing code for afib ablation + Watchman implant, which means that you’re going to start seeing way more of these procedures.

I don’t mean to be totally cynical about the way that medical incentives work, but we live in a world where financial incentives influence behavior.

And so you need to be your own advocate - and your patients’ or family members’ advocate - when this procedure is being recommended.

I’m not totally anti-Watchman, but I am a Watchman skeptic who is open to being persuaded that I’m too negative about a new technology.

I’ve written plenty about atrial fibrillation before in couple of contexts: a look at whether a small amount of afib means afib and a dive into whether atrial fibrillation ablation is lifesaving

If anyone you know has ever had a procedure like an ablation or a cardioversion, they probably had a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) done before to make sure that there were no blood clots in the left atrial appendage.

It would be insane to cut open somebody’s chest just to close their left atrial appendage.

Procedural risk isn’t nothing, but it’s a fairly safe procedure to have done and the procedural complications are generally straightforward to manage and not life changing or life threatening.

I’ve done a lot of the post procedural transesophageal echocardiograms, where you look to ensure that the device is placed well without clot or leak. My experience in that area made me skeptical about how these end up doing in patients in the real world and not just in clinical trials.

It’s fallen out of favor for a few reasons. First, it seems to be inferior to Eliquis. Second, it requires frequent blood testing. Third, it limits dietary intake of vitamin K, which is found in healthy foods like spinach.

Perhaps in the future we will have 3-D printed personal left atrial appendage closure devices.

Unless the factor XI inhibitors prove to be the Holy Grail of blood thinners that truly reduce stroke risk without increasing bleeding risk.