People in medicine love frameworks.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been taught something through the lens of a framework. The idea is that a framework gives you a scaffolding to understand complex concepts - and when you encounter something new, you can plug it into that same structure to make sense of it.

One of the most common types of frameworks doctors use is the two-by-two box. I’ve seen these applied to everything from heart failure exacerbations to abnormal heart rhythms, from test characteristics to epidemiologic exposures.

Lately, I’ve been thinking about how a few simple two-by-two boxes seem to explain a lot of the individual decision-making I see in my patients.

Doctors often frame patients through the lens of health literacy - that concept permeates a lot of these themes in this article, but health literacy is orthogonal to these boxes.1

This isn’t a grand theory of human behavior. Just something I’ve noticed over time in clinic: people tend to fall into familiar patterns.

These five boxes are oversimplifications, of course. Everything is a spectrum. People change. Context matters. But still, these themes show up again and again.

And most people will see themselves (or someone they know) in at least one of them.

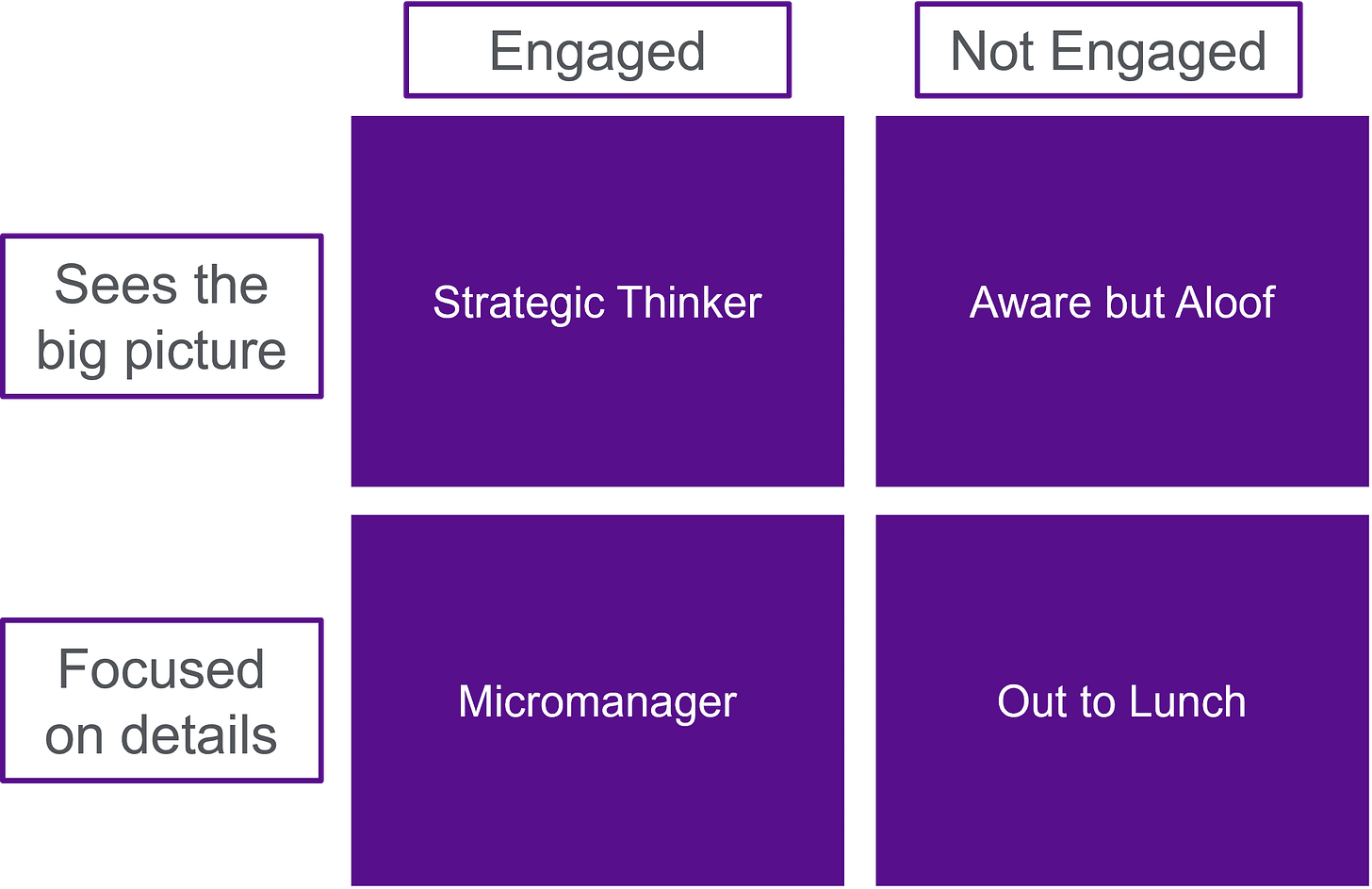

Box 1: Engagement vs. Focus

One of the biggest predictors of how people are going to do isn’t how smart they are or how much money they have. It’s their level of engagement.

Engagement is probably one of the biggest “healthy user bias” confounders in epidemiologic studies.

It’s hard to measure and impossible to fully control for, but any practicing doctor can tell you it’s real. Some people are totally checked out when it comes to symptoms, appointments, or follow-up. Others are proactive, thoughtful, and know how to advocate for themselves.

It’s not enough just to be engaged, however - it matters whether that energy is pointed in the right direction.

Being able to see the forest for the trees matters a lot when it comes to health. It doesn’t make much sense to worry about optimizing your Lipofit NMR profile if your blood pressure is uncontrolled, just like it doesn’t make sense to stress over your myeloperoxidase level if you’re not sleeping, eating well, or exercising.

Being engaged helps. But it only works if your attention is pointed in the right direction.

One of the most influential pieces of career advice I’ve ever heard from a doctor comes from Dr. Judy Hochman, the legendary cardiologist and clinical trialist. She says:

You need to be able to see the big picture but also remain focused on the details.

That’s stayed with me. It’s not about choosing one or the other. Good care (and good decision-making) comes from being able to be engaged to understand the big picture as well as how the pieces fit.

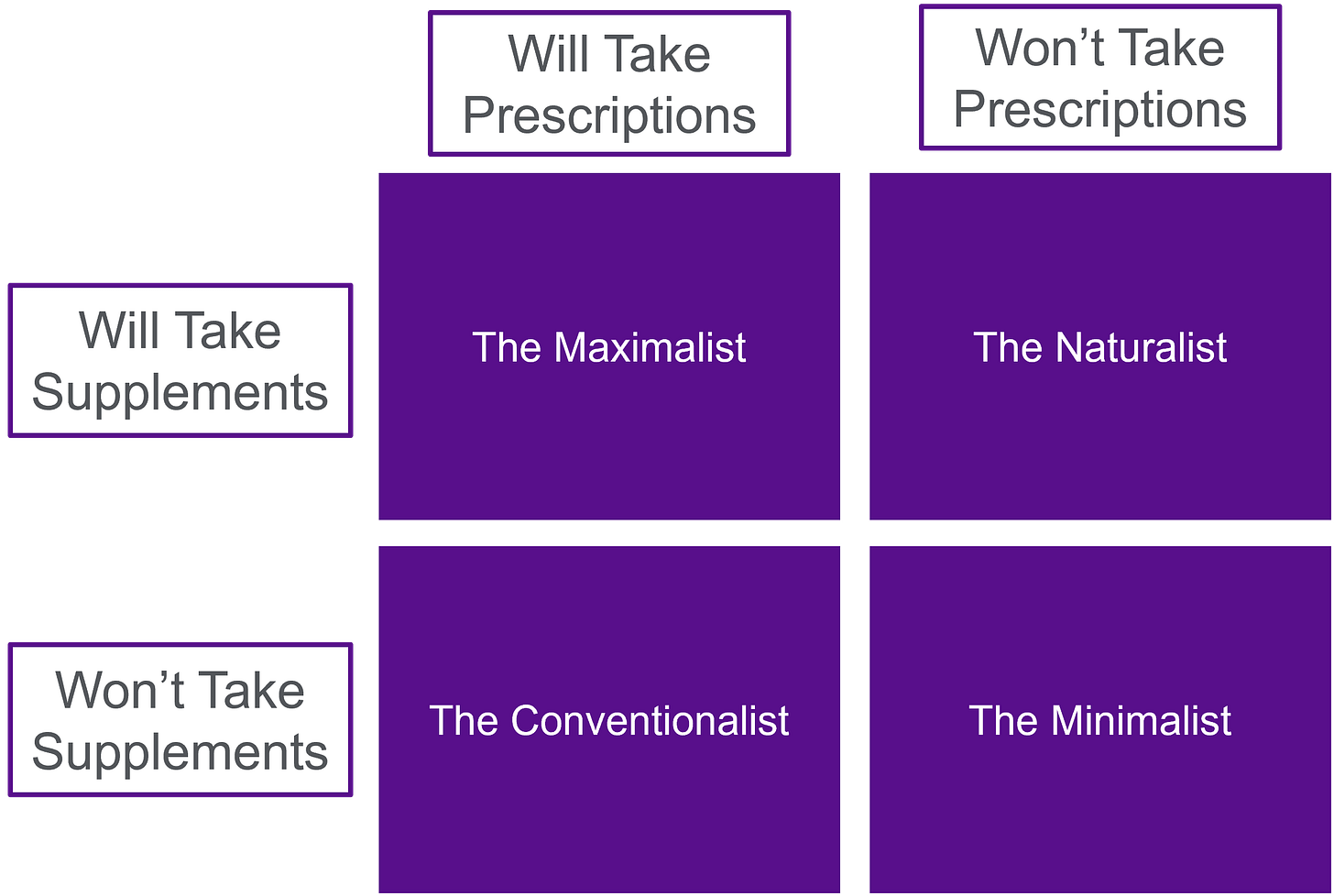

Box 2: Willingness to Take Prescriptions vs. Supplements

I’ve seen patients who fall into all 4 of these boxes. It’s fascinating to me what a black box people are as they determine their personal policy when it comes to drugs and supplements.

Some people treat anything that comes from a pharmaceutical company with deep suspicion but give supplements a complete pass.

I’ve never understood why nutritional supplements, often made by large companies or sold directly by doctors,2 don’t seem to provoke the same questions about conflict of interest or financial incentives. Only one of those industries is expected to prove safety and efficacy. And only one is consistently painted as the villain.

There’s a deep incuriosity in being willing to trust a supplement but not a medication. But the reverse exists too. Plenty of patients are happy to take prescriptions but see supplements as a waste of money or borderline pseudoscience.

Some people are open to both. Some want neither.

My general rule is: if you're trying to solve a simple problem, you might be able to get away with just ruling in or out any intervention that requires a prescription or comes in supplement form.

But if you're trying to do something complicated - like prevent heart disease, treat cancer, or put chronic disease into remission - it probably makes sense that we should be willing to use all of the tools available.

That’s why I wrote about my MAHA wishlist - if something works, we should be willing to use it regardless of whether it comes from a health food store or a pharmacy.

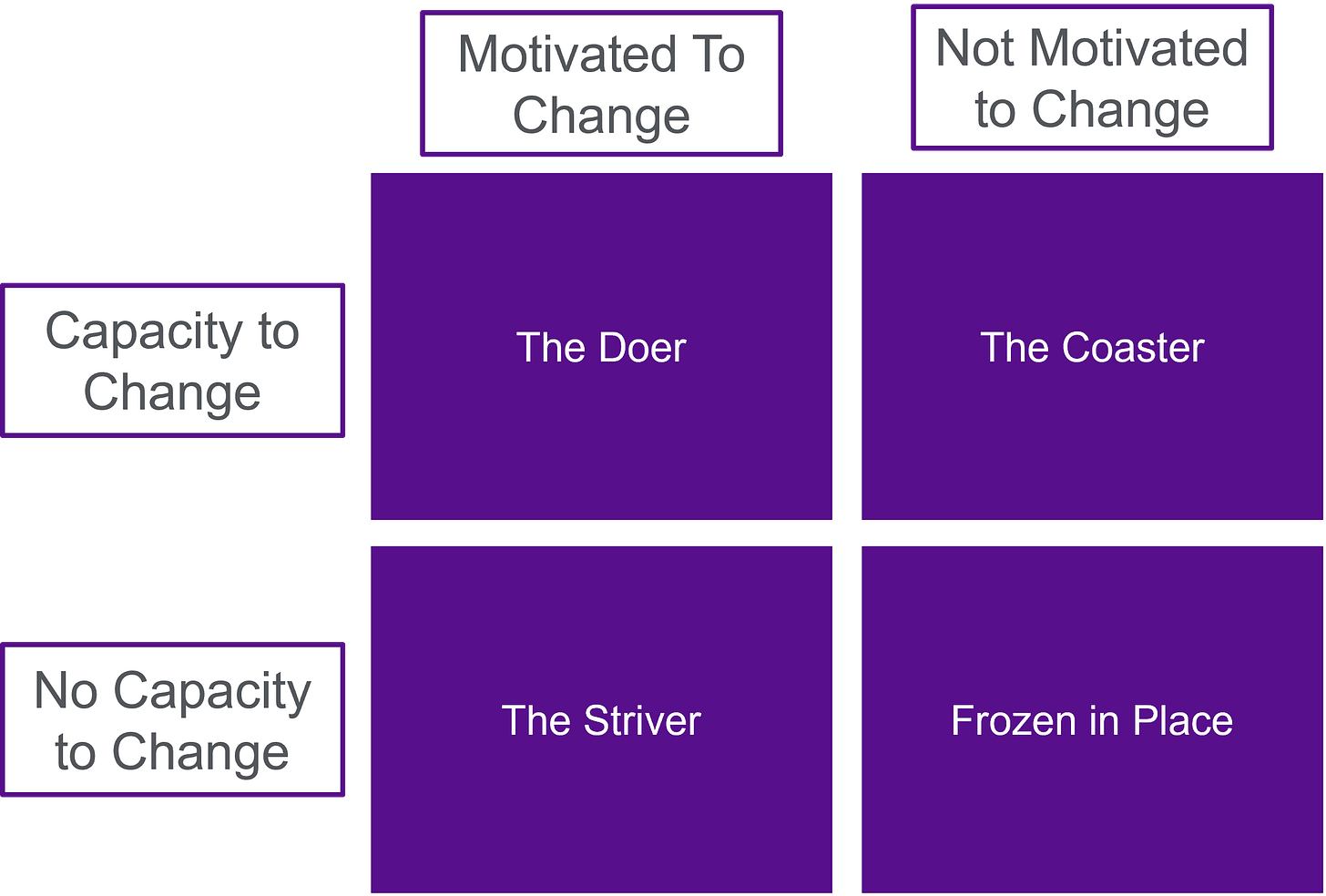

Box 3: Motivation vs. Capacity to Change

Behavior change is hard. Some people want to change but don’t have the time, support, or stability to pull it off. Others have all the resources but aren’t ready to take the first step.

A huge part of the art of medicine is figuring out where someone is on that spectrum.

If you can understand motivation and capacity, you can decide whether to try a 3-month lifestyle trial for blood pressure or just start them on medication.

And for those who are motivated but don’t seem like they know how to act, a nutritionist, a trainer, or any support that can provide frequent follow-up and SMART goals (specific, measurable, achievable, etc.) can really help.

It’s easy to assume that inaction means someone doesn’t care. But sometimes, the change just feels too big for where they are right now.

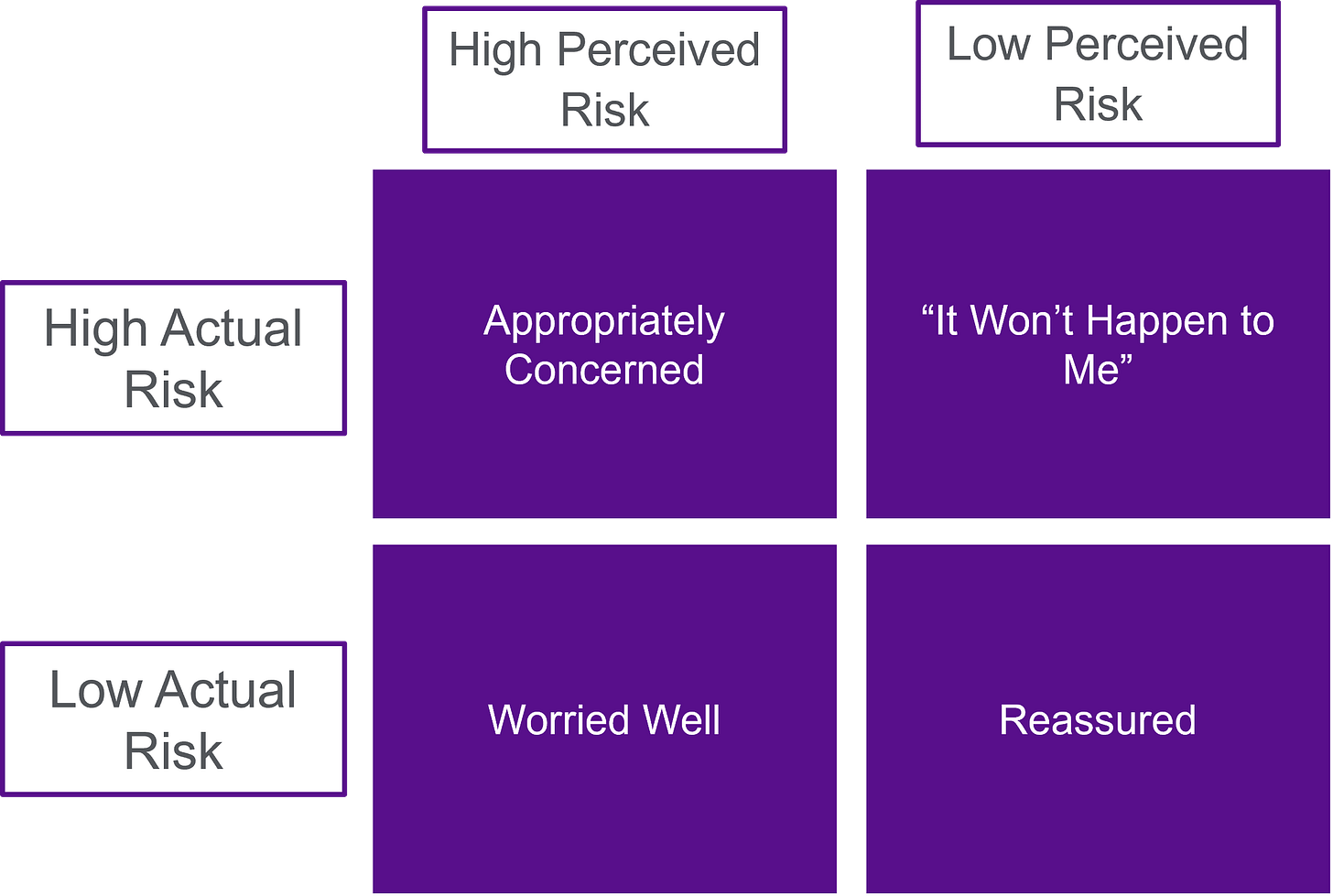

Box 4: Perceived Risk vs. Actual Risk

So much of what we do in medicine - whether it’s recommending behavior change, ordering diagnostic tests, or prescribing treatments - depends on how we understand risk.

But understanding risk is hard. And as I’ve written before, most of preventive medicine is overtreatment. That doesn’t mean prevention is wrong, it just means that some of the risks we’re trying to prevent are small in absolute terms.

When a patient’s perceived risk is way off from their actual risk, things get complicated.

Some low-risk patients are extremely anxious. They test constantly, worry obsessively, and struggle to feel reassured (even when reassurance is appropriate).

Other patients are at high risk but aren’t interested in guideline-directed treatments. Think of the young person who had a heart attack but doesn’t want to take a statin or a blood thinner.

When your risk calibration is off from your doctor’s, it creates challenges with the doctor-patient relationship.

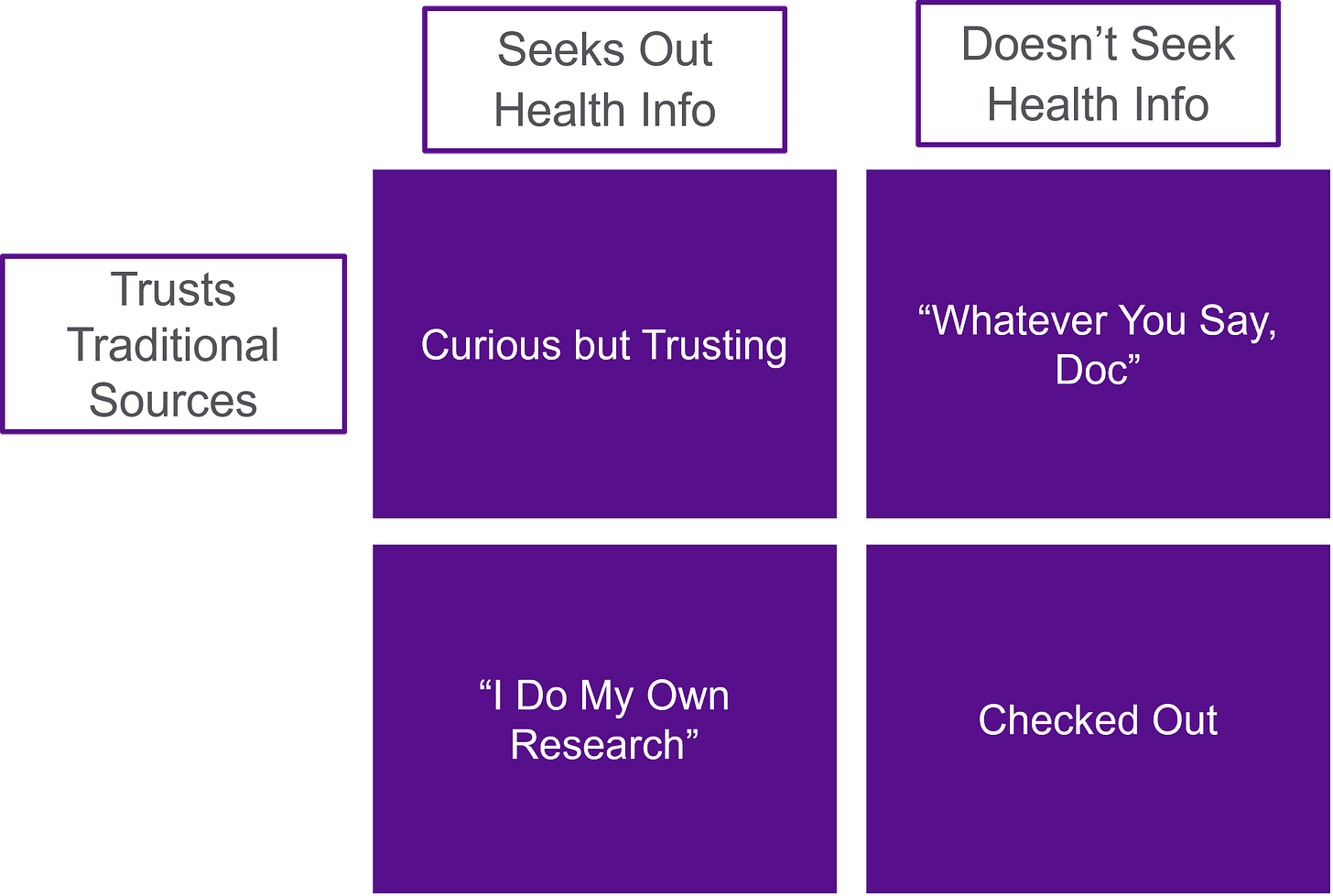

Box 5: Information Seeking vs. Trust in Experts

Some people are incredibly curious. They read, listen to health podcasts, come in with questions, check MyChart obsessively, and run their symptoms through ChatGPT. They want explanations and mechanisms. They want to know the evidence behind every recommendation.

Others are the opposite. They come in for a plan, not a seminar. They’re not necessarily disengaged, they just aren’t interested in learning all of the details.

This box overlaps with engagement, but it’s not the same. You can be deeply engaged without consuming a ton of external content. You can also consume endless health content as infotainment and not actually apply it to your own health (and also not act on any of it).

And then there’s the trust axis. Some people trust me as their doctor but not the FDA or CDC. Others trust public health organizations but are skeptical of individual clinicians. Some trust influencers. Some trust no one.

"Trust in experts" isn’t a fixed concept. It really depends on who you consider an expert.

Which is kind of the irony now: RFK Jr. is running HHS, so the people who don’t trust the system now technically are the system.

It’s not just about where people get their information. It’s about who they believe when they find it.

As many people have written (more about politics than about health): the messenger often matters more than the message.

This isn’t an exhaustive list of patient archetypes, and it’s definitely not a grand theory of behavior.

Most of these traits exist on a spectrum, and the two-by-two box is a dramatic oversimplification for most people.

But these patterns show up often. And I’ve found them useful.

Not because they explain everything, but because they offer a starting point for understanding how people think, act, and make decisions about their health.

Socioeconomic status and educational level are also concepts that have some overlap with this piece, but I think they are orthogonal concepts as well.

Supplements that are often sold (and manufactured) by the very doctors who recommend them! The degree of conflict of interest when a doctor is selling you a treatment that they recommend to you is almost too mind boggling for my brain to comprehend.

I am in the process of changing doctors. I simply can't trust anyone who says such stupid things so frequently. "We don't do that" he blurted confrontationally when I requested imaging (CAC CT angiogram), CRP, or any test other than a basic lipids panel, the only CVD risk markers he recognizes or is willing to discuss.

He then told me "I don't need that" (he was referring to himself, to be clear) when I pushed back on additional testing. He was after all telling me I was hypercholesterolemic and demanding I take statins, without ever mentioning a single number or discussing anything about statins, options, risks, etc. Zero discussion. Take this and shut up, basically. What a moron.

I do not accept that he or whatever 'we' he refers to (I am not included in his we, to be clear) have any "needs" regarding my health, and I know that he is lying to my face when he says "we don't do that". What else do doctors do but order tests, evaluate risks, advise patients appropriately, etc?

Some doctors are great. Some are just street level drug dealers with a title and a fancy office. He is that. My letter to him is a blistering condemnation of his sick care bullshit and his complete lack of respect for me. I got an updated lipids panel by my new doctor a few weeks ago. There is zero evidence of hypercholesterolemia. None.

My old doctor was just doing what's told to do. It's just 'one size fits all nonsense'. The study that matters to me is N=I. I will never be a candidate for poly-pharmacy, so I found a doctor who supports my goals and doesn't lie to me. We all deserve that.