There’s a pervasive contradiction that’s common among many people who are passionate about the power of preventive medicine:

We should be proactive in the face of early stages of a disease, but that something shouldn’t really be a prescription medication

When evidence of disease becomes apparent, we shouldn’t just wait around for things to get worse, we should do something.

But if that something is a prescription medication, then we’re too quick with the prescription pad instead of stepping back and treating the whole patient, who needs a comprehensive lifestyle intervention, not just a stent and a statin.

I have a variation of this conversation a few times a week. For many people, prevention doesn’t mean prescriptions, for reasons that are unclear to me.

Some of the better informed in this group will cite criticisms of the SPRINT trial or the weak data supporting statin use for those who have never had a heart attack as an argument against medical treatment for mildly elevated blood pressure or lipids.

For some others, there’s just a visceral reaction to being prescribed a medication for something that isn’t causing any symptoms and won’t for many years.

Prescription drugs make people concerned in a way that other health interventions do not

It’s so interesting to me to field questions from people about disease prevention.

One thing I’ve noticed is that a lot of the people who are most interested in “wellness” are often the most skeptical about pharmaceuticals.

From the wellness group, for every question I get about taking a medicine for mildly elevated blood pressure or going on a statin, there’s about 10 questions about superfoods, supplements, or fasting.

How do you think that a superfood or a supplement exerts its supposed benefit?

From a chemical compound in them that has biologic effects.

And what’s a pharmaceutical?

It’s a purified chemical compound that has biologic effects.

The difference between a drug and a supplement is that with the drug, I know what I’m getting, versus with the supplement I’m just guessing about dose, potency, and purity.

Red yeast rice wishes it were a statin, just like willow bark wishes it were aspirin.

Prevention means intervening before irreversible illness. The problem is that we can’t predict who to intervene on

I think that statins are a great example to think about when it comes to prevention.

Arguably the most impressive trial on the use of statins as lifesaving drugs that prevent heart disease is the 4S trial.

This trial looked at patients who had a history of angina or a heart attack more than 6 months before the study and randomized them to simvastatin or placebo.

Simvastatin saved lives, but it took a while for the medicine to have a benefit. This curve looks at the proportion of people who took statins compared to placebo who were alive throughout the study:

Over the course of the study, 12% of people died in the placebo group compared to 8% in the simvastatin group.

Another way of saying this is that 88% of the people given the placebo did just fine over the next few years.

The reduction in other outcomes like preventing heart attacks was even more impressive, but even for that outcome, more than 70% of people who received the placebo did fine:

What does this mean?

Well, you certainly should not take it to mean that you should stop taking the medications that your doctor prescribed because you’ll be fine regardless (you probably will be, but I’m not your doctor and this isn’t medical advice).

It also doesn’t mean that statins are useless or that we should be nihilistic about all medical interventions.

But it does suggest that not everyone benefits even from a “lifesaving” medication.

In really high risk groups, like people who have already had a heart attack, you still need to treat a whole bunch of people who are going to do just fine without your treatment if you want to save lives and prevent heart attacks.

When you take a lower risk group, the absolute magnitude of a preventive benefit is lower, even if the relative benefit is similar

Doctors are always thinking about the difference between absolute and relative risk reduction. It’s a hard concept to explain sometimes, and one of the areas where I stumble over my words with patients most frequently.

If I give you a medicine that lowers your risk of a heart attack by 50%, the magnitude of benefit that you get depends on your underlying risk.

If you have a 1% chance of a heart attack over the next year, that risk goes down to 0.5%.

Not very impressive, and I bet you wouldn’t take a medicine everyday with those numbers.

But if you have a 50% chance of a heart attack over the next year, then your risk goes down to 25%.

Now we’re talking!

Most people would choose not to take a medicine every day that has a risk of a side effects for a paltry reduction in a bad outcome.

As we saw for a group of pretty high risk patients in the 4S study, most people are going to do alright even when they’re at higher than average risk.

So when you look at a lower risk group treated with statins, like in the JUPITER trial, you see that even though rosuvastatin still saved lives compared to placebo, a lot more people were treated “unnecessarily” who would have done just fine anyway:

Most people don’t want to take prescription medications if they don’t absolutely “have to” but also want to do anything to prevent getting sick

This is the inherent contradiction in the idea of “preventive” medicine: to prevent illness, we treat a lot of people who would have done fine anyway.

When you actually look at the data on prevention, you realize that truly targeted, or “precision” therapy is impossible without a crystal ball, a time machine, or supernatural powers.

If you want to prevent disease, you need to treat people who would have done well even without your treatment.

That’s true for quitting smoking, exercise, and eating healthy just like it is true for any other drug, supplement, or medical procedure that you can think of.

The interventions we do will change your probability of getting sick, but it’s impossible to know if you truly “need” to be treated.

The doctors who specialize in prevention tend to be the most aggressive in prescribing medications

One of the most bizarre things that I’ve observed about the way this happens in practice is that a lot of the doctors who specialize in prevention are the most aggressive in terms of prescribing medications to low risk people.

That’s partly because they understand causality - treating the things that cause disease reduce the risk of getting disease - and partly because once you recognize that you can alter the trajectory of a chronic disease that kills a lot of people, it makes a lot of logical sense to do so as much as possible.

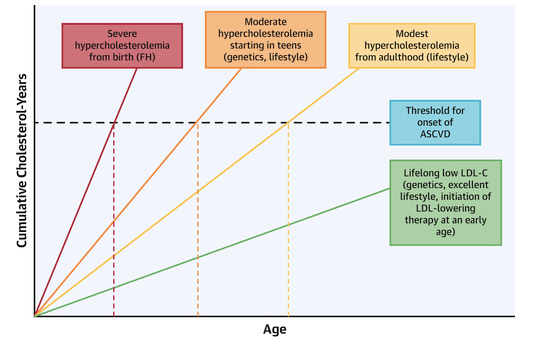

Elevated lipid levels (“high cholesterol”) provide perhaps the most illustrative example. The earlier you start with risk reduction with medications, the higher your probability of avoiding heart attacks and strokes:

But where you land on a question like “should you take a statin for prevention if you’ve never had a heart attack?” occurs where your values and preferences interact with your understanding of biology, risk tolerance, and aversion to pharmaceuticals.

This ends up being really straightforward: a literal application of preventive principles means over-treating lots of people who would never have developed disease if you had left them alone

You can argue that most prevention is actually overtreatment, and I think you’d be right.

But I’ll end with one other aspect that you should be considering when pondering these topics: asymmetric risk.

The worst outcome of having a heart attack is almost certainly worse than the worst outcome of being on a medication - so even if the likelihood of benefit is less than the likelihood of harm, it can still make logical sense to pursue the treatment.

And you can always stop a treatment if you develop side effects.

That doesn’t mean I am recommending medications for all, but I do think that the question here is more nuanced than a lot of people arguing both sides might like you to think.

Moving forward, when you hear the phrase “preventive medicine,” you should recognize that the reality of prevention is essentially just another way of saying overtreating a lot of healthy people in order to reduce a few instances of others getting sick.