It’s controversial in medicine whether screening people for disease just turns healthy humans into patients.

The argument against screening is that testing asymptomatic people doesn’t make anyone feel better and just causes harm.

That line of thinking concludes that screening scares people who shouldn’t be scared and persuades otherwise healthy folks to go for invasive and risky procedures that don’t have benefit despite having clear risk.

And I agree it’s true that often doctors can't be trusted to interpret the data from preventive cardiac testing without reflexively over-medicalizing patients, but I firmly believe this line of thinking is wrong about cardiac screening.

A few years ago, I wrote about the DANCAVAS trial, which is the best study ever done on heart disease screening.

Today, let’s take another look at the most important study ever done on the impact of cardiovascular disease screening.

The DANCAVAS Trial makes a compelling case in favor of population wide screening for cardiovascular disease.

The DANCAVAS trial was a Danish trial that tried to answer the question of whether universal screening for heart disease leads to a longer life than not screening for heart disease.

Denmark is a fantastic place to do this type of research because of the comprehensive database they have of national health outcomes and prescriptions (the Danish National Patient Registry and the Danish National Prescription Registry, in case you were wondering).

So it’s easy to track who lives, who dies, and what medications people take (and how well they take them). Plus people in Denmark don’t get lost to follow up in the same way that they might in a clinical trial done elsewhere.

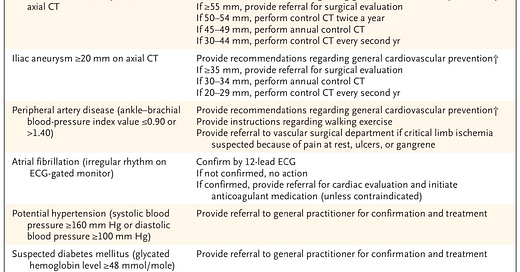

The researchers in DANCAVAS invited people from the general population to undergo screening for a fairly comprehensive list of different cardiovascular conditions:

It looks like a lot of testing, but in reality all of this can be done with a single CT scan, an EKG, a blood pressure check, and some bloodwork.

That type of testing is more in depth and more cardiac focused than what happens in most physician visits, but it isn’t an insane amount of testing to provide across a population.

Finding these conditions didn’t mean reflexively sending people for invasive procedure, it meant the basics of preventive care: blood pressure and lipid control, targeted exercise plans, repeat screening for aneurysms.

It’s a fairly conservative approach to the results.

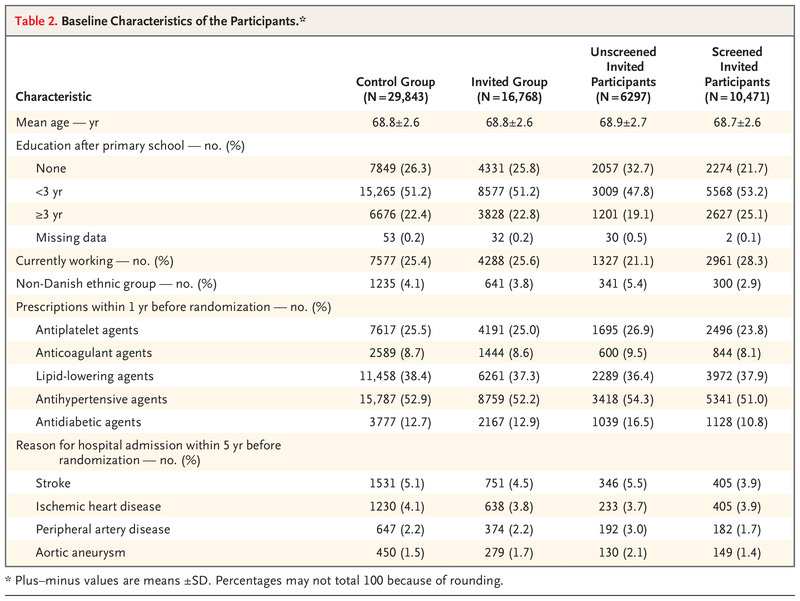

They followed patients for 5 years, tracking risk of death, heart attacks, strokes, and other serious vascular problems:

The results here are fascinating. And I want to start with why the top line conclusion if you read the abstract of the paper - that “screening did not significant reduce the incidence of death” - is almost certainly wrong.

Screening saved lives in this study

The authors conclude that the results of screening were neutral - no impact on total rate of death.

But that's almost certainly due to the short term nature of follow up coupled with the long term time horizon of atherosclerotic disease.

Look at the above table with results - you can see that 13.1% of patients in the control group died versus 12.6% of patients in the group invited for screening.

This result barely missed making a statistical calculation for significance (p = 0.06), so by the technical definition, it wasn’t a significant outcome.

So how can I reasonably conclude that the study saved lives when the authors (and stats) didn’t?

Well, for starters, the margin of error here is entirely on the side of saving lives (the confidence interval for the hazard ratio of screening invitation was 0.90-1.00).

And when you add in what we know about the people who were actually screened and the timeline of heart disease, I think it’s easy to make the case that screening people helps them live longer.

The analysis is just looking at the effect of “being invited for screening,” not actually screening people

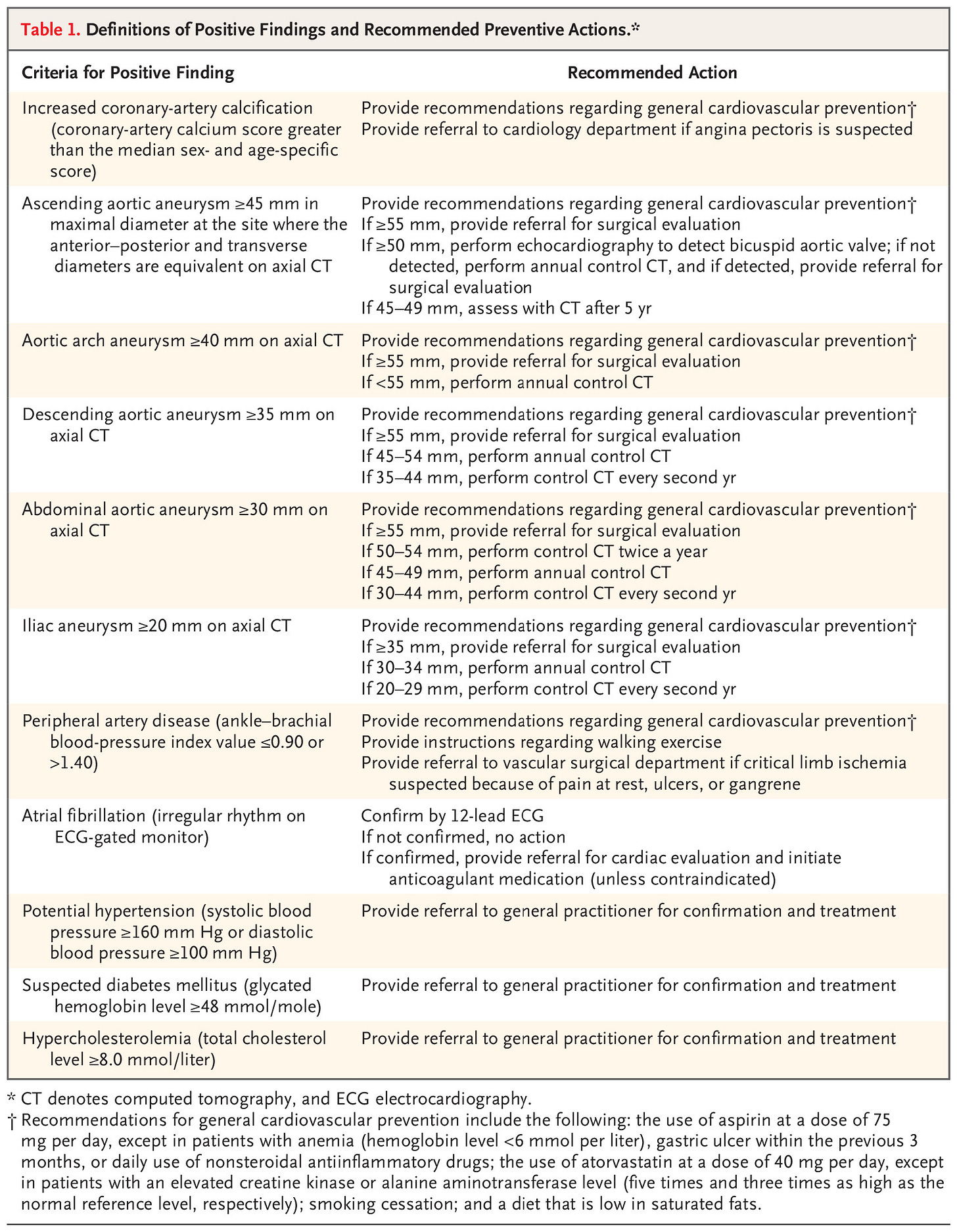

Look at this table from the paper on the differences between the group that was invited for screening and got screened versus the group that was invited for screening and didn’t get screened:

The people invited for screening who weren’t screened were the ones at higher risk of bad health outcomes. Compared to invited + screened, the invited + not-screened group was:

Less well educated

Less likely to be employed

Less likely to be of Danish ethnicity

More likely to have a history of stroke and peripheral vascular disease

In other words, the people who would probably derive the greatest benefit from screening weren’t actually screened and so couldn’t possibly derive a benefit from screening.

So to see a benefit of screening when you’re screening a lower risk group but doing your analysis of survival with the whole group suggests that screening higher risk people will lead to an even greater benefit of screening.

The timeline of heart disease progression takes many years, and this study wasn’t designed to assess that

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is a process that takes decades, but the DANCAVAS study followed people for about 5 years after screening.

When you combine what we know about heart disease treatment - it alters the trajectory of a disease that takes decades - with the results of a relatively short term follow up after screening, I think it makes the case to screen even more compelling.

Screening for heart disease means finding a lot of things that we can do something about. There’s compelling data to support the hypothesis that treatment = risk reduction with both high blood pressure and high LDL cholesterol levels.

The benefits of treating these risk factors compound, just like investing money compounds over time.

If you have control over these things early and maintain that control over decades, true universal heart disease prevention really starts to seem possible.

You can bend the risk curve for almost everyone.

There’s a reason that Albert Einstein once called compound interest “the most powerful force in the universe.” Lifelong control of heart disease risk factors is the compound interest of cardiovascular health.

But the process starts with knowing risk, and that's where screening comes in.

The results from DANCAVAS are deeply persuasive - screening for heart disease works.1

Knowing your own personal risk is the point of screening - after all, heart disease is the number 1 killer, but DANCAVAS provides a compelling argument that it doesn’t have to be.

As long as we keep in mind that screening exists to decide on medical treatment, not on unnecessary invasive procedures.