Most people over the age of 40 die from heart disease, cancer, or Alzheimer’s.

So anything that we can do to delay or prevent the onset of these diseases generally means a longer and higher quality life.

A lot of the general preventative strategy in avoiding the big 3 starts with metabolic health and avoiding metabolic syndrome, which increases risk of Alzheimer’s, cancer, and heart disease.

But there are disease specific things that we can do here.

I’ve written before about the one-sized-fits-all approach to heart disease, otherwise known as the polypill, but just giving a drug cocktail to everyone alive is certainly an inelegant method of prevention.

Screening for heart disease and then giving individual-specific prescriptions and lifestyle plans is a more targeted way to prevent cardiovascular problems.

The idea of screening for cancer has made its way into the popular consciousness - you’ve probably heart about mammograms, colonoscopies, Pap smears, and PSA checks.

Heart disease has sort-of gotten there; there’s a reason we check cholesterol levels and blood pressure as part of a standard physical. But we haven’t fully gotten to the point of deploying more thorough population based screening for heart disease.

A new study out of Denmark suggests that we should.

The concept of screening is important to understand

Before we get into the details of the trial, I think it’s worth a short digression on the rationale behind any kind of screening.

Not everyone gets heart disease, and there’s a long latency period from when there is evidence of disease present on medical testing but before symptoms develop.

That state - when disease is present but hasn’t caused symptoms - is called “subclinical disease,” and it portends a worse heart disease prognosis moving forward.

Finding subclinical disease before it becomes symptomatic only matters if you can do something to change the trajectory of the illness.

If you don’t have tools to help, finding something early doesn’t really make a difference.

That means it’s easy to be fooled by data from a screening test - this is the concept of lead time bias, probably best understood through the lens of cancer screening.

Lead time bias basically means that finding a disease earlier may just increase the amount of time you live with a known disease versus an unknown disease, rather than actually changing your survival:

A new study out of Denmark supports the idea that screening for heart disease actually makes a difference

A recent trial out of Denmark called the DANCAVAS trial tried to answer the question of whether universal screening for heart disease leads to a longer life than not screening for heart disease.

Denmark is a fantastic place to do this type of research because of the comprehensive database they have of national health outcomes and prescriptions (the Danish National Patient Registry and the Danish National Prescription Registry, in case you were wondering).

So it’s easy to track who lives, who dies, and what medications people take (and how well they take them). Plus people in Denmark don’t get lost to follow up in the same way that they might in a clinical trial done elsewhere.

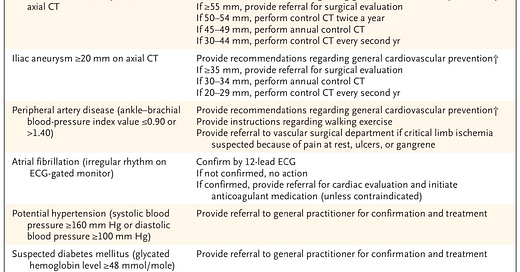

The researchers in DANCAVAS invited people from the general population to undergo screening for a fairly comprehensive list of different cardiovascular conditions:

It looks like a lot of testing, but in reality all of this can be done with a single CT scan, an EKG, a blood pressure check, and some bloodwork.

So not that much different than what happens in many physician visits.

Treatment for these conditions was then initiated based on the recommended actions in the above table, which includes referral to the appropriate medical providers.

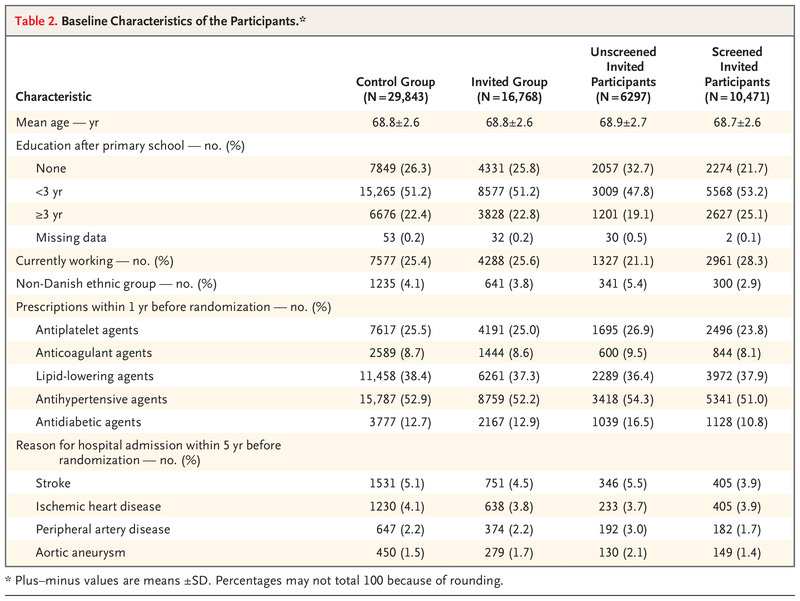

They followed patients for 5 years, tracking risk of death, heart attacks, strokes, and other serious vascular problems:

The results here are fascinating. And I want to start with why the top line conclusion if you read the abstract of the paper - that “screening did not significant reduce the incidence of death” - is almost certainly wrong.

Screening saved lives in this study

The authors conclude that the results of screening were neutral - no impact on total rate of death.

But that’s more due to a statistical quirk than because it’s what they really found.

Look at the above table with results - you can see that 13.1% of patients in the control group died versus 12.6% of patients in the group invited for screening.

This result barely missed making a statistical calculation for significance (p = 0.06), so by the technical definition, it wasn’t a significant outcome.

Why did I conclude that the study saved lives when the authors (and stats) didn’t?

Well, for starters, the margin of error here is entirely on the side of saving lives (the confidence interval for the hazard ratio of screening invitation was 0.90-1.00).

And when you add in what we know about the people who were actually screened and the timeline of heart disease, I think it’s easy to make the case that screening people helps them live longer.

The analysis is just looking at the effect of “being invited for screening,” not actually screening people

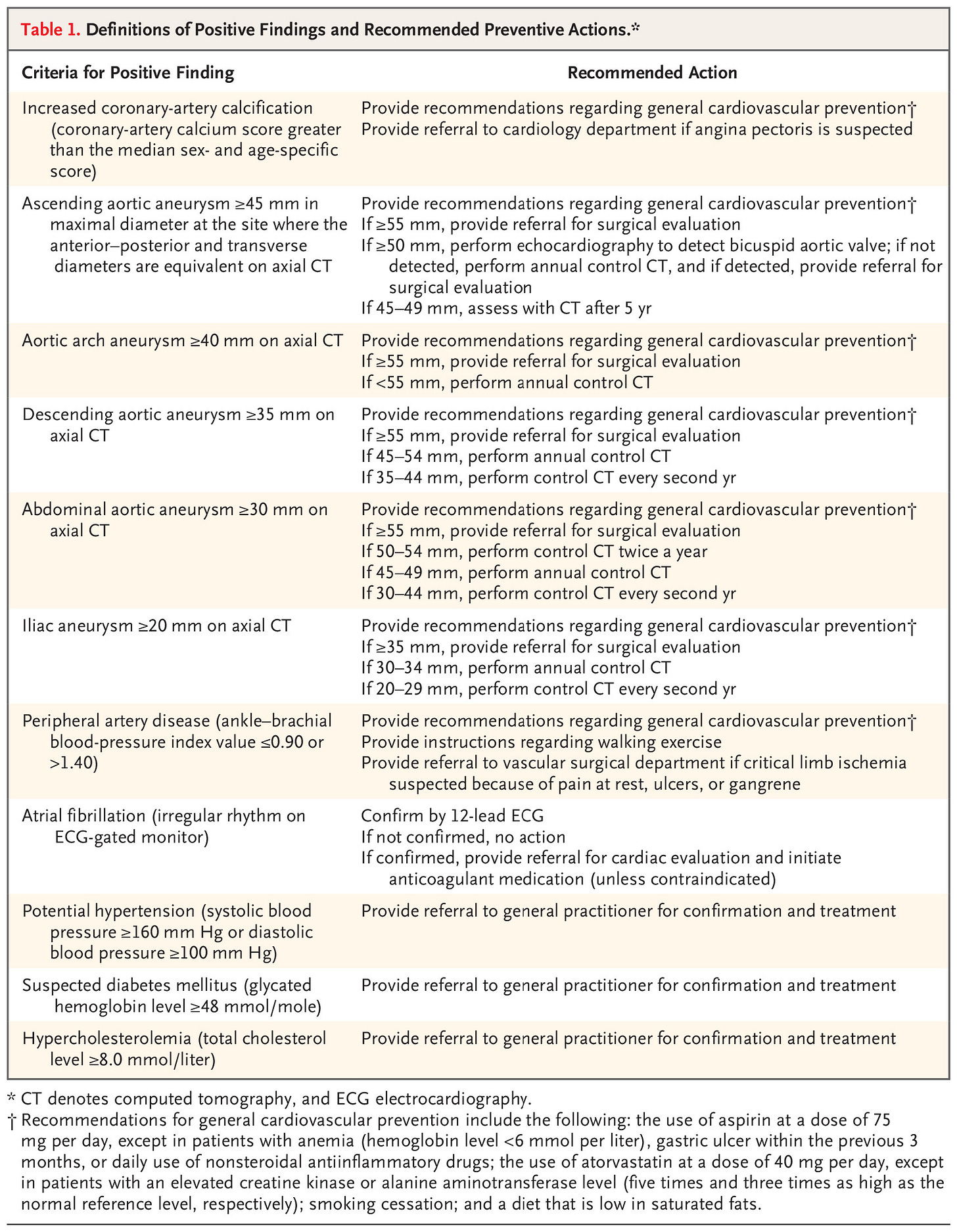

Look at this table from the paper on the differences between the group that was invited for screening and got screened versus the group that was invited for screening and didn’t get screened:

The people invited for screening who weren’t screened were the ones at higher risk of bad health outcomes. Compared to invited + screened, the invited + not-screened group was:

Less well educated

Less likely to be employed

Less likely to be of Danish ethnicity

More likely to have a history of stroke and peripheral vascular disease

In other words, the people who would probably derive the greatest benefit from screening weren’t actually screened and so couldn’t possibly derive a benefit from screening.

So to see a benefit of screening when you’re screening a lower risk group but doing your analysis of survival with the whole group suggests that screening higher risk people will lead to an even greater benefit of screening.

The timeline of subclinical heart disease progressing to clinical heart disease is long

I’ve written before about how heart disease is a process that takes decades.

The DANCAVAS study followed people for about 5 years after screening.

When you combine what we know about heart disease treatment - it alters the trajectory of a disease that takes decades - with the results of a relatively short term follow up after screening, I think it makes the case to screen even more compelling.

Screening for heart disease means finding a lot of things that we can do something about

I’ve written before about the way that treating the things that cause heart disease has a benefit that increases over time.

There’s compelling data to support the hypothesis that treatment = risk reduction with both high blood pressure and high LDL.

The benefits of treating these risk factors compound, just like investing money compounds over time.

If you have control over these things early and maintain that control over decades, true universal heart disease prevention really starts to seem possible.

You can bend the risk curve for almost everyone.

There’s a reason that Albert Einstein once called compound interest “the most powerful force in the universe.”

Lifelong control of your heart disease risk factors is the compound interest of your cardiovascular health.

It starts with knowing your own risk.

So what are you waiting for?