Most people having surgery get sent for “medical clearance” — a preoperative visit with a primary care doctor or cardiologist to assess their risk.

The idea of “clearing” someone for surgery is kind of absurd.

No one has a crystal ball, and there’s no magical stamp that ensures a complication-free recovery.

And yet, I get messages all the time from surgeons and anesthesiologists asking: “is this patient cleared?”

The reason preop medicine exists isn’t a joke. Surgery is risky - you’re sedated, cut open, inflamed, and often bleeding - and the physiologic stress can trigger cardiac complications.1

It’s easy to write about this in a flippant way that ignores the fact that these decisions are often challenging.

After all, the last time I wrote about this stuff, I called preop visits “the biggest waste of time in medicine:”

But in real life, things are often more complicated than the picture that’s painted by a newsletter on Substack.

Let me share a recent case that perfectly illustrates just how convoluted preoperative risk assessment can become

The preop testing and treatment cascade

A recent patient I saw came to see me for a second opinion.

He was in his 80s, had no history of heart attack or stroke, never had chest pain or trouble breathing, and was being planned for spinal surgery for life limiting back pain.

Because of his limited exercise capacity, his primary care doctor had sent him for a nuclear stress test.

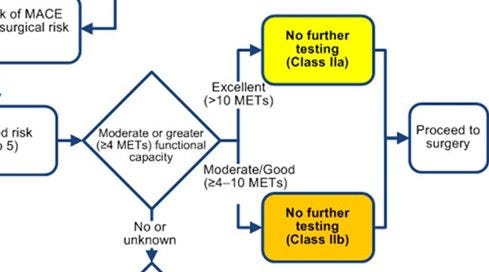

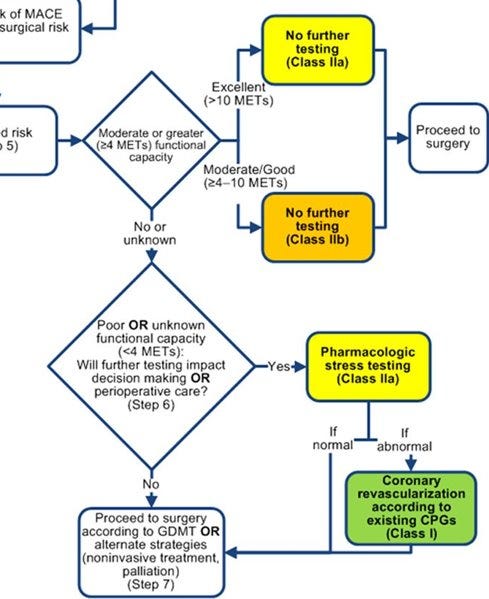

It’s not insane to send do this - it’s actually in the ACC/AHA preoperative guidelines to send people for a nuclear stress test before surgery if their exercise capacity is uncertain:

But as you can probably guess, the stress test was abnormal.2

So he had a coronary CTA, which was also abnormal.3

That led to a cardiac catheterization, which revealed a significant blockage in a major artery.

Now his plan changed: he was told to delay surgery, get a stent and wait 6 months.

Except... his pain was unbearable. He didn’t want to wait. And he came to me asking the question we’re all really trying to answer in preop medicine:

“Am I going to die on the table?”

He comes to see me asking whether he’s going to die on the table and how high his surgical risk really is

Anytime I have an important clinical question to answer, I always look to see whether there’s a large randomized controlled trial to help me answer it.4

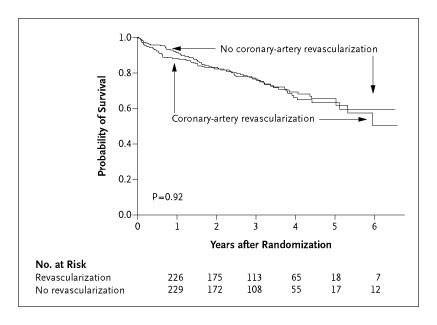

In this case, there is. The CARP trial, looked at patients with stable coronary disease who were planning major vascular surgery. It randomized them to either get coronary revascularization before surgery or go straight to surgery without stents or bypass.

The results were clear and completely neutral.5

Survival was the same either way. Here’s the kicker: fixing blocked arteries did nothing to reduce surgical risk.:

So if you believe CARP — and it’s hard not to — the answer is simple: stenting this patient changes nothing. He should go ahead with surgery.

Why did this all happen?

This is where the logic breaks down.

Surgery is an inherently risky undertaking and if we’re going to do testing beforehand, shouldn’t we have a clear sense of how that testing changes surgical outcomes?

If fixing blocked arteries doesn’t reduce surgical risk, why do we send people for caths after abnormal stress tests?

And if we don’t act on the cath, why do the CTA?

And if the CTA leads nowhere, why do the stress test?

And if we wouldn’t act on the stress test, why are the guidelines recommending one?

It’s circular logic. And it’s frustrating.

Because each step feels defensible in isolation — but collectively, it rarely changes management.

Risk is not the same as modifiability

Here’s the core insight:

Understanding risk is not the same thing as being able to modify is.

This patient had no cardiac symptoms. He was living his life until he needed spine surgery. Then, all of a sudden, he was sent for three cardiac tests, diagnosed with coronary disease, and told to postpone the surgery that would improve his quality of life.

And what did we learn? That he might be at elevated cardiac risk.

What we didn’t learn is how to change that.

That’s the uncomfortable truth of preop medicine.

The hubris of doctors means that we often confuse risk stratification with risk intervention.

But just because we can find a risk doesn’t mean we can fix it.6

How I practice

I almost never send patients for preoperative stress tests unless I would be sending them for a stress test otherwise.

That means that unless a patient has life limiting symptoms of chest pain or trouble breathing, I don’t think that we gain much ability to modify surgical risk from sending them for a bunch of cardiac tests.

Stress testing still has an important role to play in taking care of patients, but not in the box-checking way that they are often used.

The guidelines are, in my view, too casual in recommending stress testing based on a vague assessment of function status.

The result is wasted money, wasted time, unnecessary radiation, and the illusion of precision.

Of course, each case is different.

But applying unwavering criteria to every patient that you see is a recipe for being a bad doctor.

Why this case matters

This case isn’t just about one patient.

It’s about how medicine works. Or how it sometimes doesn’t.

It’s about how easy it is to fall into the trap of doing more tests without asking what they’re really for.

“Mundane” decisions like should this patient get a stress test? often reveal the deepest flaws in our clinical reasoning.

They force us to confront the limits of what we know — and what we pretend to control.

Sometimes the best we can do is admit that we don’t have a great answer.

But we can at least stop pretending we do.

The biggest risk of a cardiac complication during surgery is actually related to the amount of blood lost during surgery, which we can’t do anything to modify during the clearance process.

Stress tests are often reported as “normal” or “abnormal” but really these results exist across a spectrum. The patient in this story had a very high risk stress test, with a large, severe, reversible anterior perfusion defect.

The CTA showed a calcium score of around 4000 and severe multivessel coronary artery disease.

I often tell my residents that most “studies” on a topic aren’t management changing because most of them are observational studies - they observe the world but don’t do experiments. Observational research is the type of work that almost every study that you read about in the media describes. This type of research is almost always inherently confounded and should be used for hypothesis generation to be tested in an experiment rather than drawing important conclusions about how to make decisions or manage patients. Having your practice frequently influenced by observational data probably means you’re more gullible than you should be.

If you want to read into it in more detail than you probably should, you see that up front, the group that had their blocked arteries fixed (revascularization) actually had a lower survival than the group that didn’t. It suggests the possibility - note that I didn’t say proves - that having your arteries fixed may actually increase your risk up front. If we believe that’s true, it’s likely related to the challenges of managing blood thinning medications around the time of surgery in someone who just had blocked arteries opened up.

The question of “why doesn’t fixing arteries modify risk?” is a really interesting one. It probably has to do with the mechanism of a classic heart attack being different than the mechanism of just a decrease in bloodflow because of a blocked artery. In a heart attack, a plaque in the walls of the arteries bursts and causes a blood clot. It’s not the same thing as a chronically blocked artery, which has a stable plaque without a blood clot. Fixing a severe blockage doesn’t modify the rest of the plaques in the artery walls, which can still burst and cause heart attacks.