Widaplik, Polypills, and the Messy Business of Medical Progress

And now comments open in this newsletter

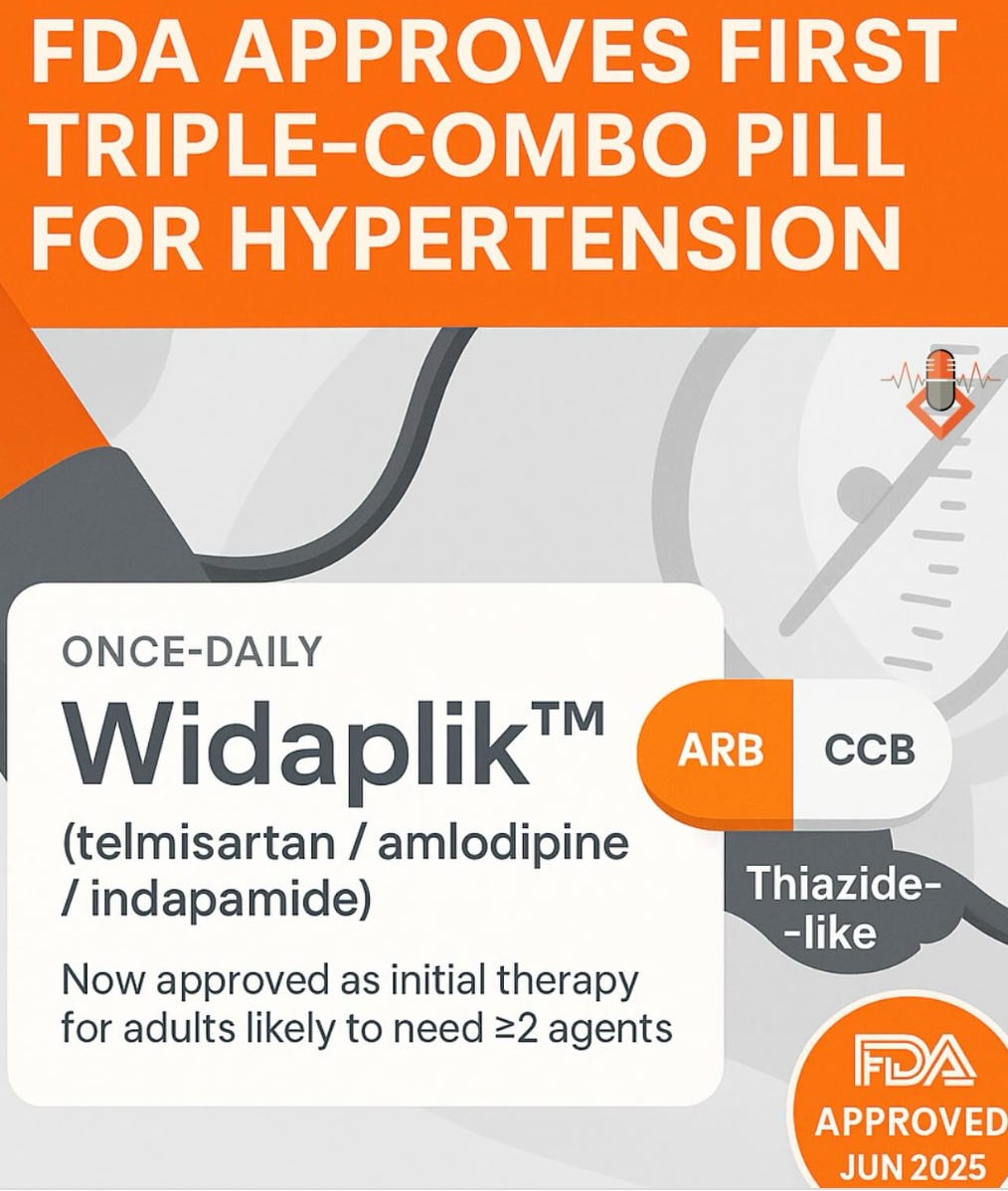

Earlier this summer, the FDA quietly approved a new triple-drug hypertension pill called Widaplik. It didn’t make many headlines, but it probably should have.

Widaplik combines three blood pressure medications - telmisartan, amlodipine, and indapamide - into a single, fixed-dose pill. It’s the first FDA-approved triple-combo antihypertensive that can be used as initial therapy, not just a fallback when others fail.

If this drug is priced reasonably, it’s going to be incredibly useful at controlling blood pressure and preventing heart attacks and strokes.

The Power of Simplicity

I’ve written before about polypills, which I think are the most incredible innovation that no one is talking about in medicine.

Polycap, a five-drug cardiac prevention combo that includes aspirin, a statin, a beta blocker, and two different blood pressure medications has been clearly shown to reduce cardiovascular events.

The concept seems almost too obvious to get excited about - it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to realize that we might reduce heart attacks by giving people aspirin, statins, and blood pressure meds.

But being able to actually implement a strategy like that is just an enormous challenge.

Getting people to take even a single daily medication is harder than most non-clinicians realize. Multiple pills? Different refill schedules? Variable side effects? That’s a lot of friction. A fixed-dose combination makes adherence easier. It also reduces costs, simplifies logistics, and minimizes the burden of titration.

Widaplik offers another benefit too: electrolyte balance. Indapamide tends to lower potassium, telmisartan tends to raise it, and amlodipine doesn’t affect it much. The net effect may help reduce the risk of major derangements, which is something that clinicians constantly worry about when initiating multi-drug regimens in real-world patients.

More Pathways, Better Biology

But my excitement isn’t just about convenience. It’s also about biology.

One of the recurring themes I’ve written about multiple times before is that inhibiting multiple biological pathways tends to work better than hammering just one. We’ve seen this in heart failure, HIV, tuberculosis, cancer, and lipid lowering.

The pathophysiology of hypertension is complex (sodium retention, vascular resistance, sympathetic tone, RAAS activation) and often there's no single “root cause” to target.

In the future, we might be able to precisely tailor medications to each patient’s mechanistic fingerprint. But we’re not there yet. So a well-designed polypill that hits several mechanisms at once makes a lot of sense.

As long as the cost is reasonable, I’m in.

Under the Radar, But Not Unimportant

The Widaplik approval didn’t generate much buzz. And in a media environment that loves miracle cures and gene therapies, maybe that’s not surprising.

But it’s still disappointing.

We tend to fetishize innovation and ignore implementation. A polypill isn’t sexy, but it is pragmatic. It’s not curing rare diseases or using AI to solve unsolvable problems. It’s just helping more people treat conditions with meds we already know work.

And that, frankly, is where most of medicine’s real gains happen.

Innovation vs. Regulation: The Fall of Vinay Prasad

At the same time Widaplik was quietly clearing regulatory hurdles, another story dominated FDA-related headlines: the controversial decision not to approve Sarepta’s gene therapy drug Elevidys for muscular dystrophy.

The fallout from that decision included the resignation of Vinay Prasad from the FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research.

If you follow medical Twitter or read Substacks like Sensible Medicine, you already know that Vinay Prasad is a divisive figure. He’s sharp, contrarian, sometimes brilliant, and often insufferable. He built his brand during the pandemic by disagreeing (often sarcastically and condescendingly) with the mainstream medical consensus on non-pharmacologic Covid mitigation measures and vaccination policy.

And while many of my colleagues in academic medicine celebrated his departure from the FDA with quite a bit of schadenfreude, my own reaction was different.

I’ve learned a huge amount from Vinay Prasad. His book (cowritten with Adam Cifu) Ending Medical Reversal was one of the most influential things that I’ve read in medicine. I interpret clinical trials differently - and better - because I’ve read his work. And I’m incredibly appreciative to him for helping to form my perspective on the importance of understanding the strength of the evidence behind our medical interventions.

His commentary can often be nuanced, insightful, and original. And in a world where too many doctors think exactly the same, hearing a different point of view sharpens all of our minds.

Unfortunately, he’s also a troll who uses hyperbole, sarcasm, and insults to dismiss people who disagree with him or who he thinks are idiots.1 He’s earned his reputation as being kind of an asshole, which is why I think so many of my colleagues are happy that he resigned.

The Sarepta Question

Vinay Prasad’s resignation doesn’t make our drug approval process any easier. And it doesn’t help resolve the much harder question: is Sarepta’s drug Elevidys is a net positive for patients with muscular dystrophy?

Because here’s what’s missing from all of the commentary on Vinay Prasad and on this drug: the FDA’s job is really freaking hard.

Every FDA decision lives in a world of tradeoffs, and most decisions there have life or death stakes.

Approve a drug that turns out to be harmful, and you’ve made a error of commission and something actively dangerous is on the market. Fail to approve a helpful drug, and you’ve made an error of omission and withheld a potentially life-altering treatment from people in need.

Both mistakes are real. Both matter. And they require a level of judgment that’s easy to second-guess and incredibly hard to get right.

And almost all of the incentives are in favor of more lax approval. Think about it - drug companies, patient advocacy organizations, doctors, researchers, biotech investors - everyone on the sidelines is cheering for approval, almost regardless of whether that’s truly the right thing for patients.2

But we don’t talk enough about how valuable the FDA is. For all its flaws, the U.S. FDA is the envy of the world.

Our regulatory process - although it’s imperfect - remains the most thorough, science-driven in the world. And while you can argue with some of its decisions (on Sarepta, on Aduhelm, on COVID boosters) it’s worth stepping back to appreciate how complex those calls really are.

Two Paths to Progress

Widaplik and Sarepta couldn’t be more different: one is a humble blood pressure pill, the other a gene therapy for a devastating disease. One is under-hyped; the other may be a breakthrough. But both highlight how complicated medical progress can be.

We need smart regulation. We need rigorous evidence. We need implementation strategies that recognize the limits of human behavior and the barriers to care.

And we need to be real that a lot of these regulatory decisions are really tough calls that I’m glad I don’t have to make.

But it’s always important to remember that not every advancement needs to be revolutionary or controversial. Sometimes, a quiet little pill that helps more people actually take their blood pressure meds is enough.

And also, this newsletter is now open for discussion

For a while, I kept comments and likes turned off on this newsletter.

That was intentional in response to some of the replies I got from my posts. I wanted this space to be focused, distraction-free, and not part of the kind of noise that often fills internet comment sections.

But over time, a few things have become clear:

Readers like you have real insights and good questions that are worth sharing

There’s value in thoughtful dialogue and good faith disagreement

So starting today, comments and likes are back on.

I am not interested in a comments section that doesn’t stick to the actual content.

And please don’t post a YouTube video as though that makes your point compelling - those are almost universally uninteresting, unscientific, and unrelated.3

This is a newsletter written for people who have an attention span for reading and not just watching.

My goal is to make sure the conversation stays respectful and useful - and adds something to the discussion.

If you’ve got a reaction, a question, or something that resonated, I would love to hear it. And if you just want to quietly read, that’s always welcome too.

And thank you, as always, for reading.

The idea that people can disagree in good faith is really important when it comes to public health policy, where judgment and values are as important as science. Prasad’s social media persona could be so unnecessarily combative and dismissive of people who truly think differently (and aren’t stupid, or arguing in bad faith). That’s a huge part of why so many of my colleagues in medicine have such strong negative feelings about him. It’s ironic that Prasad is one of the founding writers of Sensible Medicine - a place for thoughtful, nuanced discussion and good faith disagreement.

And so, I think it’s worth noting that Vinay was forced to resign over not approving a drug that had real controversy around its safety.

While there is a lot of great content (and even science content) on YouTube, the average piece of scientific discourse there is poison for your mind. My strong advice - stay away from there unless you already have a firm grasp of the topic at hand, because if you don’t you’re likely to come away more poorly informed than you were to start.

I am not a clinician - just a person who loves learning, especially about medicine. I enjoy your newsletter (and Dr. Cifu’s) because it is so refreshing to read sensible, well-thought out articles. Thank you for all you do.

After listening to all of Prasad's podcasts on VPZD, I agree the man knows his stuff and he gets frustrated when he thinks decisions are made based on poor evidence. I tried to convince him to be more respectful in his critiques, but I don't think he reads comments. Perhaps he doesn't know you can catch more flies with honey than with vinegar. I wonder if he gained any insights from his brief stint at the FDA that he will share on podcasts? I'm also interested to see what Makary will do when under pressure to make vaccines harder to get, as he does believe in the evidence vaccines are safe and effective. As for polydrugs, my dog takes telmisartan and amlodipine and it wasn't enough, so I added taurine and his BP came down further and stayed down. I made my own polydrug in a pill pocket! :)