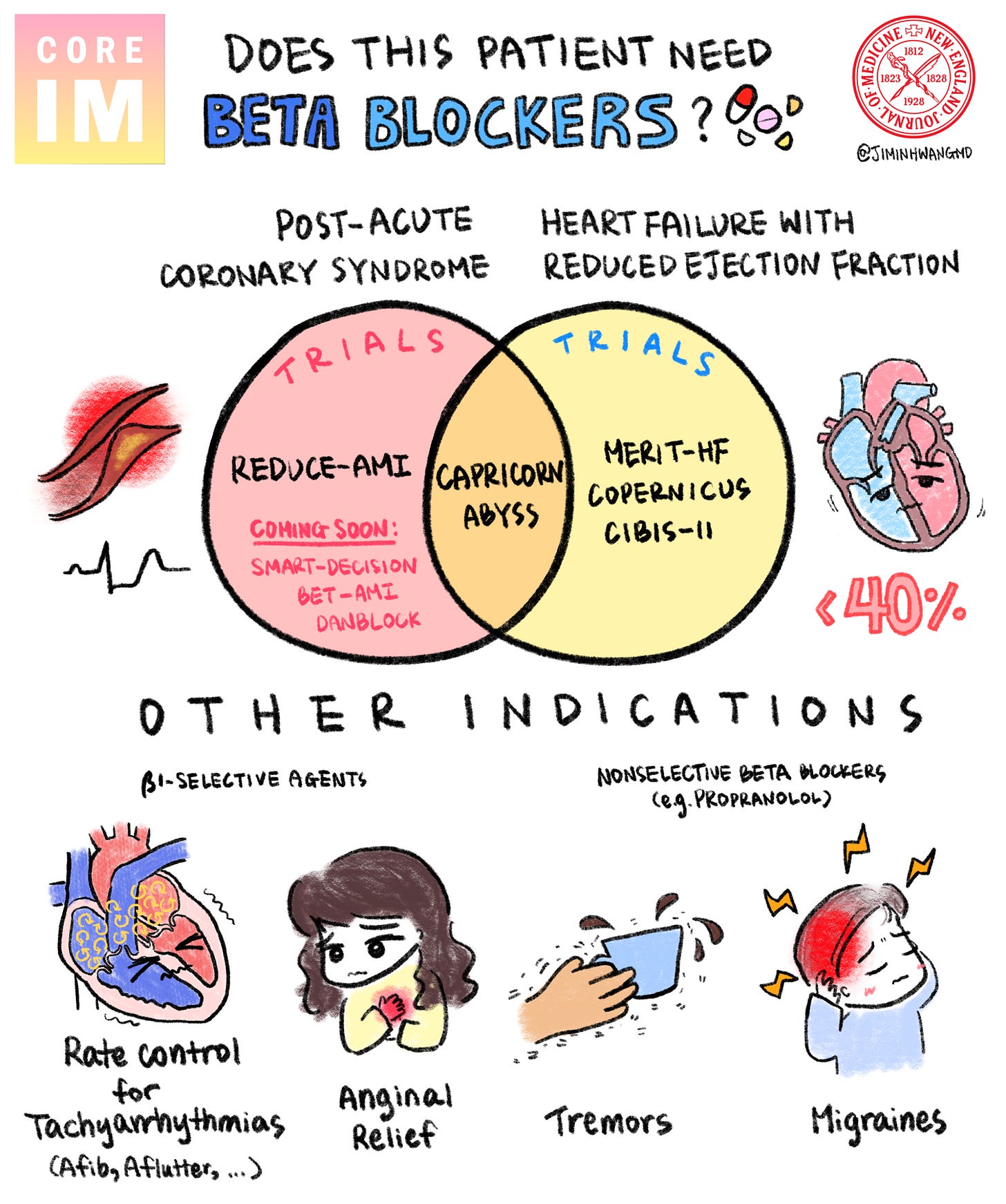

For the latest episode of the Beyond Journal Club podcast (a collaboration between Core IM and the New England Journal of Medicine), we took a look at the REDUCE-AMI trial, which has a lot of important implications for how we interpret evidence and how we think about clinical care.

The trial asked a simple but provocative question: Should every patient get a beta blocker after a heart attack,1 even if they’re doing fine otherwise?

REDUCE-AMI makes us think about one of the most deeply entrenched practices in cardiology.

Below you can find some of my additional thoughts - some of which made it into the podcast, and some of which didn’t. I hope you enjoy the podcast.

Why Beta Blockers Were Always the Default

For decades, prescribing beta blockers after a heart attack has been clinical canon.

The practice is so entrenched that it's a quality metric hospitals are evaluated on. Miss too many post-MI beta blocker prescriptions, and you risk financial penalties.

But here’s the thing: most of the data supporting this practice is from the 1980s and early 1990s. The world of cardiology has changed dramatically since then. Back then, we didn’t have:

Stents and modern revascularization

Potent dual antiplatelet agents like clopidogrel, prasugrel, or ticagrelor

Widespread statin use

Ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors, or bempedoic acid

We’re playing a different game now. And that means the rules might need to change.

What the REDUCE-AMI Trial Found

REDUCE-AMI is the first large randomized trial to directly ask:

Do beta blockers help patients with preserved ejection fraction after a heart attack?

The short answer: no.

In over 5,000 patients, beta blockers didn’t reduce the risk of death, hospital readmission, or even arrhythmias like atrial fibrillation. These were well-treated patients, on modern therapies, with normal post heart attack cardiac function.

It's the kind of result that makes you take a hard look at what you thought you knew - that old adage they tell you in medical school, that in 10 years half of what you learn will be wrong, we just don’t know which half.

More data is coming, and we can expect other trials over the next year that will influence how firmly we believe the REDUCE-AMI results to be true. But unless they show something wildly different, REDUCE-AMI may mark the beginning of the end for routine beta blockers in this population.

Three Big Lessons from REDUCE-AMI

1. Every Practice in Medicine Needs an Expiration Date

Medical evidence ages. Treatments that made sense in 1985 may not make sense today because so much about the rest of our care changes. That’s not a knock on the past. It’s a sign that each decision needs to be continually reevaluated.

But when our practices don’t evolve with the data, we risk undertreatment, overtreatment, side effects, and missed opportunities to simplify care.

We need to keep asking: Does this still make sense, in the context of how we treat patients today?

2. Sicker Patients Are Sicker

This study enrolled a relatively healthy group: post-MI patients who maintained good ejection fraction. That’s a big deal.

Much of medicine comes down to identifying who is the vulnerable patient that needs us to intervene.

There’s a reason we tell interns that we want you to be able to identify sick versus not sick - deciding which patients are sicker helps us make a lot of treatment decisions on the margins for people who might not fully fall into Table 1 of a clinical trial.

The converse is true too - healthier patients are healthier.

One of the hardest skills in clinical medicine is knowing when not to treat. And REDUCE-AMI is a reminder that if someone is doing well, less may be more.

3. Goodhart’s Law Strikes Again

Goodhart’s Law (borrowed from economics) says:

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

In healthcare, this shows up all the time. We turn surrogate markers - like LDL levels, blood pressure, or yes, even beta blocker prescription rates - into metrics of quality.

But metrics shape behavior. When beta blockers become a benchmark for good care, doctors are incentivized to prescribe them on the margins and every edge case is more likely to end up with a beta blocker prescription if it changes your quality metrics.

And once you create incentives around a metric, it becomes incredibly hard to walk it back, even if the evidence evolves.

If we don’t update our quality metrics with the same urgency that we update our clinical practice, we’re just going to be algorithm monkeys left chasing numbers that don’t matter.

Why This Matters for the Future of Healthcare

As AI becomes more integrated into care delivery and decision-making, the metrics we choose will matter more than ever.

The trend of metricizing what we do in health care isn’t going away. It’s accelerating. And because AI moves us towards optimization, as these tools become integrated into medicine, expect the issue to get more entrenched rather than less.

And so if our targets are outdated, misaligned, or based on shaky evidence, we run the risk that the further metric-ization of health care will make things worse for our patients.

So when you look at something like REDUCE-AMI, it’s not just a trial about beta blockers. It’s a canary in the coal mine that suggests how flexible our systems are is going to matter a lot.

Whether we can evolve when the data tells us to - and whether we use the right data to guide us - will determine if things evolve for the better.

🎧 Listen to the full episode of Beyond Journal Club wherever you get your podcasts. We dig deep into the trial design, the history of beta blockers post-MI, and what this means for real-world patient care.

I’d love to hear your thoughts—especially if this changes how you think about treatment after heart attacks.

The medical term for a heart attack is a myocardial infarction or MI. If you aren’t in the medical world, the term MI might seem foreign, but that’s how doctors talk about heart attacks. There are two different classifications based on the EKG, which are STEMI and NSTEMI. Those names just refer to how the EKG looks when the patient comes to medical attention. The actual differences can be way more subtle, and that paradigm is changing, but you should be aware of some of the nomenclature.

Share this post