Talk about microplastics is everywhere - I can’t imagine that anyone reading this hasn’t been inundated with micro plastic content.

And everything that you see sounds totally ominous.

Almost all of the content takes it for granted that *obviously* microplastics cause disease, and so *of course* we should be strategizing ways to remove them from our lives.

But is the evidence really all that persuasive?

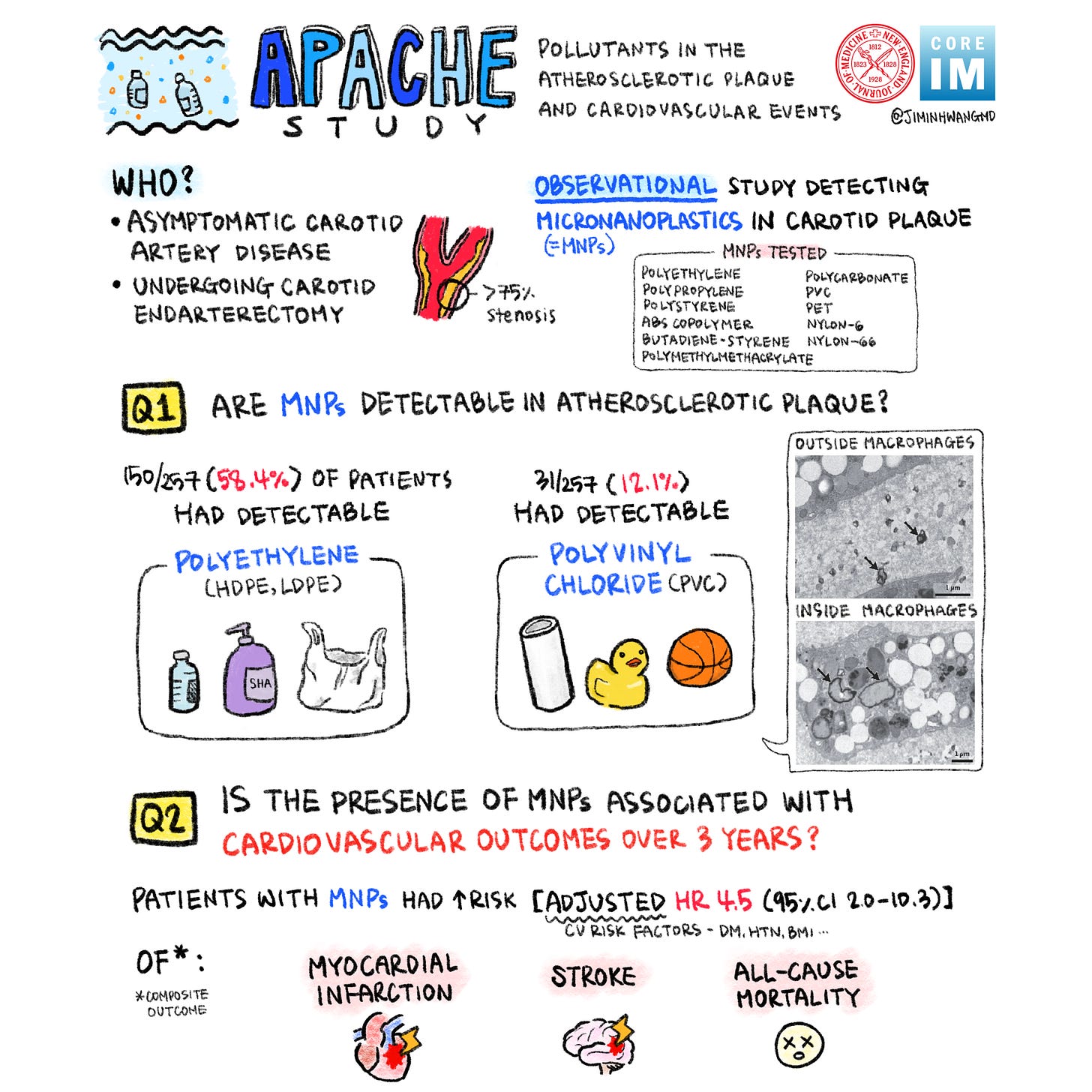

This is a podcast on the APACHE study - a paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine on the link between microplastics seen in cardiovascular plaque and subsequent development of bad outcomes.

For the podcast, we had the chance to interview Dr. Phil Landrigan, who wrote the NEJM editorial on the paper, as well as Dr. Jane Leopold, the Deputy Editor of NEJM responsible for shepherding this paper to publication.1

The podcast is the latest installment of the Beyond Journal Club series that I’ve been working on with Core IM and the NEJM Group.

This is probably the most important study to date on the question of microplastics and human disease

This study looked at people who had surgery to remove a blockage in their carotid arteries and found that more than half of them had actual microplastics in their artery plaques.

The people who had plastic in their artery plaques had more than 4 times the risk of bad cardiac outcomes compared to the group that didn’t have any plastics in there.2

It’s the first study that ever demonstrated a link between plaque visually seen in tissue and subsequent risk of disease - this is a really important paper and a big deal in terms of building the science.

And while it sounds totally damning - like this should be the smoking gun linking microplastic exposure to disease in humans - I don’t think that’s the right takeaway.

There are quite a few reasons that I’m skeptical this study proves microplastics cause human disease:

We don’t know what makes people who have microplastics in their carotid plaques different than people who don’t have microplastics in those plaques. It’s just as plausible to me that sicker people are more likely to incorporate microplastic into their plaque and so the presence of microplastics is actually just a marker of someone’s health status.

We have no idea about the exposure differences - do people without microplastics all have glass food storage containers and all cotton clothes while the people with microplastics microwave plastic tupperware and drink from disposable water bottles?

There’s no dose response relationship seen in the plaques - higher levels of microplastic should lead to more inflammation if they are causative, but in this paper that relationship didn’t exist.

We don’t have any evidence of a temporal relationship between plastic exposure and subsequent risk of disease. That relationship - exposure preceding disease - is part of the Bradford Hill Criteria that help us understand how likely a correlation like this is to be causative.

I don’t think that this study is a “call to action” for doctors

Many people looked at this paper as a “call to action” that “demands urgent attention.”

I’ve had colleagues describe talking about trying to reduce plastic exposure with our patients as an “easy win.”

I disagree with that comment.

While the evidence raises questions, it’s not accurate to say that we know plastic causes human disease.

I’m not there yet, and I don’t think that a microplastic discussion has any place in a doctor’s appointment unless a patient brings it up.

And even if a patient wants to talk about that question, I try to redirect the conversation.

We have a much higher level of confidence that exercise is good for you than that plastic is bad for you.

We know that treating high blood pressure lowers your heart disease risk and we don’t know whether avoiding plastic tupperware has any impact.

There are just so many places where the quality of the evidence gives us clear guidance about what to do and the microplastic question is certainly not one of them.

We need to be disciplined in the way that we interpret the science here. The chain of causality hasn’t been built, and so maybe microplastics cause human disease, but maybe they simply don’t.3

But even if you are persuaded that microplastics cause human disease, it’s not clear what you should do about it

The biggest place where I think we are left with questions is what to do about this.

Removing plastic from your life is expensive and inconvenient - and, more importantly, we don’t know how much that impacts your total plastic exposure.

Plastic is everywhere on Earth, from the deepest parts of the ocean to the highest mountains of the Himalayas.

We get plastic into our bodies from ingestion, inhalation, and skin exposure.

None of the evidence points to a clear direction on where the bulk of that exposure comes from.

On top of that, it’s not clear that all plastics are equal when it comes to biologic impact.4

There’s an argument to be made that if we, as physicians, are thinking about changing our own behavior that we owe it to our patients to share that with them.

And I understand that point, even if I disagree with it.

We should be rigorous about the way we interpret evidence for our patients - and unless a discussion about microplastics is filled with caveats - I strongly believe that the opportunity cost of discussing this stuff during a clinic appointment is too high.

Remember, time is limited, and what you talk about is what you prioritize.

I’m going to save my time with my patients to discuss the things that I am more confident about in two ways:

I feel more certain that there’s a direct link between the risk factor and cardiovascular disease

I feel a higher level of confidence in the things that we can do to mitigate that risk

So until that evidence gets stronger,5 I’m going to stay focused on discussing heart disease prevention in a way that reinforces my level of confidence in the level of evidence.6

If you want to see more of the interview with Dr. Landrigan, you can watch it here.

That risk ratio is after adjusting for a number of other variables that play a role in heart disease

That’s not a comment that we should be seeking out ways of increasing our plastic exposure. I can’t imagine a case that these things are beneficial to human health. But clear evidence of harm is different than possible evidence of harm.

Interestingly, in this study, the authors were looking for 11 different microplastic particles in the carotid plaques, but only found 2 present. Does that mean the other 9 are harmless?

Which it very well might!

One of the questions that I’ve been asked is what type of study I would need to see to feel more confident. The initial thing that I’m looking for is a clear link between exposure via different mechanisms (inhalation vs ingestion, heated plastic vs room temperature, water vs food) and microplastics in human tissue. If this is a topic of interest, I’ll think about expanding it in future newsletters.