Some people find low carb diets incredibly effective for weight loss.1

But there are people who do well with weight on a low carb diet that have a dramatic rise in their LDL cholesterol numbers.

We’re talking an LDL that can double or triple when someone adopts a ketogenic diet.

This group of people has been termed “Lean Mass Hyperresponders” or LMHRs.

LMHRs are metabolically healthy - meaning they don’t seem to be overweight or have insulin resistance - but develop an incredibly high rise in LDL when on a low carb diet.2

You can see LDL levels of over 300mg/dL in this group - insanely high numbers that suggest a genetic defect in lipid metabolism, but it’s really just a product of the diet.

There’s a lot of interest in low carb advocates of whether this rise in LDL leads to an increased risk of heart disease.

Whether that rise in LDL is dangerous in the setting of an otherwise healthy person has real implications for the group of people that likes to be on a keto diet but has this crazy rise of their LDL.

A recent study sought to answer this question - does the elevated LDL that results from a keto diet increase progression of cardiovascular disease?

Let’s take a look at the KETO-CTA study.3

KETO-CTA did annual imaging of the coronary arteries in these patients

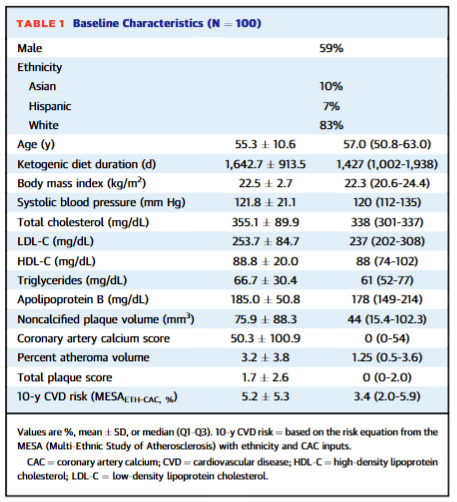

Study design here was very interesting - they took patients with a very high LDL in response to a low carb diet and followed them for a year.

They did coronary CTA tests at the beginning of the year and the end of the year.

They monitored their bloodwork, including their LDL cholesterol levels.

They made sure that these patients were otherwise healthy - no diabetes, no chronic kidney disease, no chronic inflammatory disease, and no low HDL/high triglyceride panels that would suggest insulin resistance.

Patients were not allowed to be on medications that lower LDL like statins or PCSK9 inhibitors.

And, most importantly, they had insanely high LDL levels, with an average of over 250mg/dL:

They mostly had coronary artery disease at the beginning of the study, but they had overall low cardiovascular risk on account of their generally good health.

The purpose of the CTA testing at the beginning and end of the study was to evaluate progression of cardiovascular disease.4

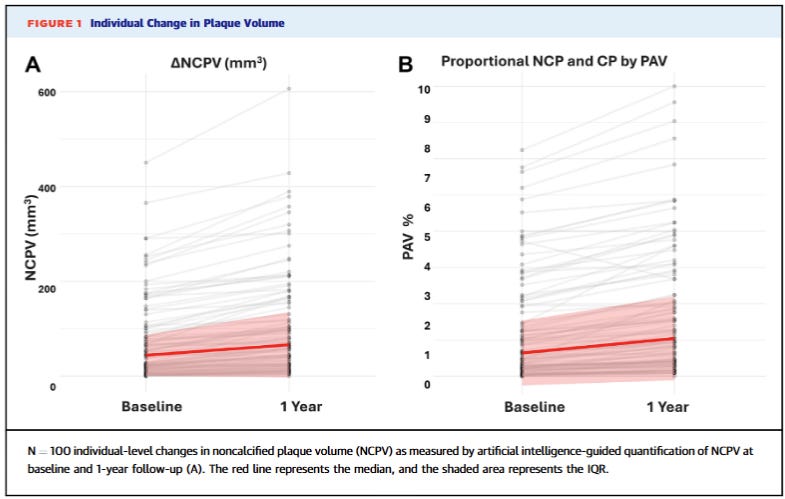

The results were really interesting - quite a bit of progression of heart disease on this diet

The people in this study had significant progression of heart disease over the course of a year in this study:

They didn’t all have a gigantic or rapidly progressive growth in their plaque, but they certainly had progression of heart disease.

And while the best predictor of plaque progression in this group was having plaque to begin with - after all, sicker patients are sicker - the rate of plaque progression in the group was actually quite alarming.

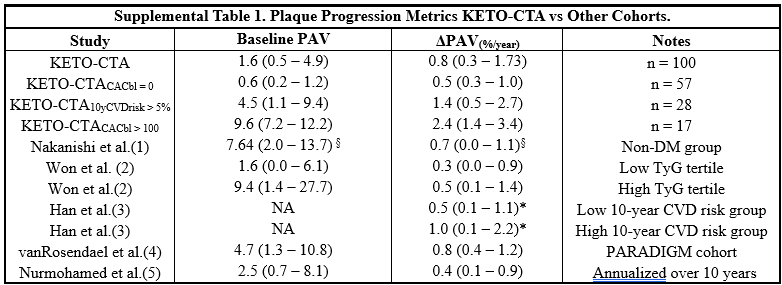

Here’s a comparison of the KETO-CTA group to other longitudinal studies that have looked at the progression of plaque:

It’s a complicated graphic, but I think it’s worth unpacking - the KETO-CTA group had a faster rate of progression of cardiovascular disease than essentially any other group that’s been studied like this.

This is important because the KETO CTA group, by almost any conventional approach to risk assessment, were much healthier than the other cohorts except for their LDL.

The most important take home is that the KETO-CTA group had a faster rate of progression of cardiovascular disease than has ever been published.

So that means to me that a low carbohydrate diet that comes with a marked rise in LDL cholesterol is a diet that makes heart disease progress faster.

You can look at what predicted risk in this study - presence of plaque, more so than LDL levels - and try to do a subgroup analysis and sort out how to stratify risk, but that’s a much less important aspect of interpreting this study than the fact that plaque progression was faster than other groups that have been studied.

Fast progression in heart disease is bad, but you wouldn’t know that from the social media discourse.

Influencer discussion focused on the fact that LDL-C and ApoB levels did not predict progression in this study

The lack of concordance between LDL or apoB was the point that most of the social media discussion on this paper were focused on:

But there are a few problems with looking at this study to suggest that apoB and LDL don’t cause heart disease.

First - all of these patients had sky high LDL and apoB. Does it matter if your LDL is 200mg/dL or 250mg/dL? I’m not sure that it does - they are both incredibly elevated.

Second - patients had been on a ketogenic diet for almost 5 years, so they had quite a bit of exposure to this diet and the associated lipid levels.

Third - they had incredibly fast progression of their cardiovascular disease, which suggests to me that this type of response to a ketogenic diet portends a concerning cardiovascular prognosis.

Overall, this is an alarming study for anyone considering a keto, carnivore, or super low carb diet that has a big rise in their LDL-C (or apoB)

It’s hard to draw major conclusions about cardiovascular disease in a short term study in such a small group of people.

That said, seeing plaque progression that is faster than ever recorded in a group of patients who are metabolically healthy but have sky-high LDL is quite alarming.

It’s easy to look at the narrative being pushed on social media - no link between LDL or apoB and progression of plaque on CTA - and start feeling like this type of diet has been proven to be safe.

But that’s wrong - it hasn’t been proven to be anything, including dangerous.

This is an alarming data point to me, but it’s certainly not the last word on the subject.

I continue to feel that a low carb diet can be a great health choice for many people, but it’s not the only diet option that can be great.

Unfortunately, if you have a big rise in LDL in response to this type of diet, I’m concerned by what we are seeing.

There’s no reason that we can’t hold a few important concepts in our heads simultaneously when it comes to this type of diet and the possible risk:

Very low carb diets make some people feel good and may improve markers of blood sugar and blood pressure

These diets cause a large rise in LDL for some patients

That rise in LDL may be problematic when it comes to heart disease

There is nothing contradictory about eating the diet that makes you feel well and treating the associated rise in LDL as a potential risk worth mitigating

That last point - that you can feel good on a diet while not ignoring the fact that the LDL rise may be problematic - is vital.

There’s a real focus in the low carb diet community about disproving the LDL hypothesis, which I suspect is because it conflicts with the perspective that a low carb diet is good for everyone, all the time.

But I think the evidence for the LDL hypothesis is really strong, and the KETO-CTA study reinforces that viewpoint.

It’s pretty easy to reconcile these two perspectives.

If a low carb diet makes you feel good but your LDL skyrockets, then stay on that diet and use medications to lower that number and therefore lower your cardiovascular risk - there are quite a few different options that are safe and effective.

I’m really glad to see the results from KETO-CTA and I give the authors a lot of credit for conducting this study.

It’s not the last word, but it’s an important one as we think about how to counsel these patients in a situation with some true clinical uncertainty.

Overall, it seems that low carb diets are probably a bit more effective for weight loss than conventional diets. That comes from randomized control trials like this one and this one. A lot of the reason why that weight loss isn’t maintained is that people don’t stay on the diets long term. But regular readers of this newsletter will know that I’m in the nutrition agnostic community - I think that many different dietary patterns can be effective in establishing excellent health. In practice, low carb works for some people but doesn’t work for others.

I’ve seen this so frequently that one of the questions I ask people when they come to see me with a very high LDL is whether they’ve been restricting carbohydrates before we consider doing any genetic testing.

The authors inappropriately call this a “trial.” It’s not a trial - a trial requires an experiment. This is a study that follows a group of patients with serial monitoring to the natural history of heart disease.

The primary outcome was “non calcified plaque volume” or NCPV, which is a measure of plaque in the arteries that hasn’t calcified. I tend to think of non calcified plaque as the dangerous kind, because that’s what can burst and cause a heart attack. The calcified stuff (what you see on a calcium score) isn’t technically the most risky plaque in the arteries.