How my medical thinking changed in 2022

Consider this post to be a year in review of my own medical practice.

For those of you who aren’t in the medical field, this post may feel a bit like inside baseball.

But some of the things that have changed my practice are probably things that your own doctor has been exposed to and been thinking about.

So this isn’t your standard medical year in review - it’s my own personal medical year in review.

The revolution of weight loss drugs has changed the way I think about obesity

I’ve written before about safe and effective weight loss drugs after the STEP 1 trial on Ozempic came out, and I wrote again about these drugs after my early experience with tirzepatide, AKA Mounjaro.

It’s pretty clear to me that these drugs are big business and legitimate breakthroughs that may actually reverse the trajectory of the obesity epidemic.

This has changed the basic way that I think about obesity, too.

These drugs seem to work by promoting satiety - they take away hunger in such a profound manner that many of my patients describe that they just lose interest in the late night snacking that used to be their weight loss downfall.

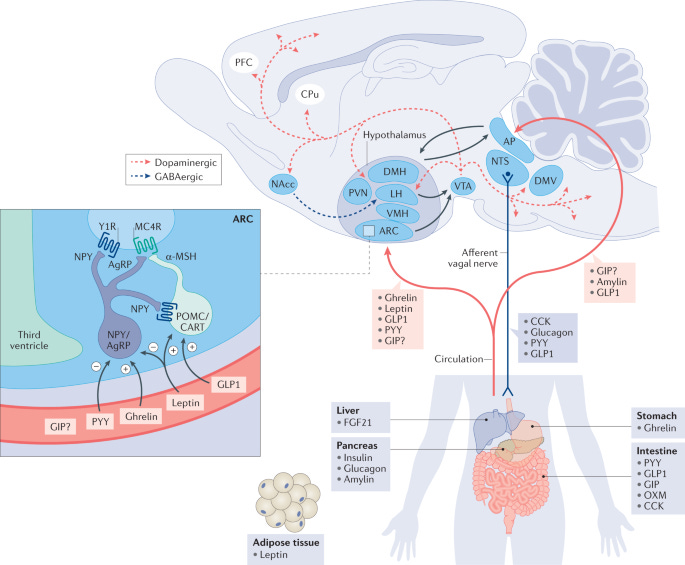

The interesting thing to me is that they don’t exert all of their effects on fat tissue or in the GI tract - they actually work in the brain as well.

A couple of patients have actually described to me the way that they never had the ability to see the role that overeating played in their lives until they started these drugs, because they were just so damn hungry all the time.

Hearing the description that people give about their experience on these drugs has made me consider the role of the hypothesis that the modern environment with plentiful, low-satiety calories leads to neurologic dysregulation of appetite, which “breaks” our fat regulation through insulin resistance, leptin dysregulation, and ghrelin stimulation:

To put this in plain English: my experience with tirzepatide and semaglutide has fundamentally changed the way I think about the causes of obesity and the amount of control we all have over our weight.

Hopefully 2023 sees these drugs more easily available and more affordable for the people who would benefit from them.

Early, aggressive treatment for cardiovascular risk

I’m a cardiologist with a focus on the secondary prevention of vascular disease.

The majority of patients I see are folks who have already had a heart attack or a stroke, and the goal of my work is to prevent another one.

But the deeper I get into the literature here, the more persuaded I am that our traditional paradigm to assess cardiovascular risk is a bit off.

When we discuss cardiovascular risk, one of the most common tools that we have available is a 10 year risk calculator.

Unfortunately, heart disease takes decades to happen. Thinking on a 10 year risk horizon leads to a lot of people having heart attacks and strokes that they shouldn’t have.

The more I look into the data on the early and aggressive treatment of the things that cause heart disease, the more persuaded I am that early treatment works.

Now, early treatment is going to be different things for different people - it doesn’t just mean throw everyone on a statin (although maybe it should).

It also means not ignoring elevated blood pressure.

It means considering whether you should lower your numbers even if they aren’t that high.

The skeptics like to point to a study like this one, a meta-analysis of over 65,000 patients followed for about 4 years that didn’t show a reduction in death with statin therapy. These folks were high risk, but never had a heart attack or a stroke.

If you just read the abstract, you see a null result and think there’s no benefit.

But when look at the sum total of the data, you can see that the confidence interval barely crosses 1, which means that the range of possible true results leans heavily toward the favorability of statins:

And since heart disease takes decades to take root, my view is that seeing the strong hint of a benefit in such a short period of time should be thought of differently than the authors report it.

So my preventive instincts have become more inclined towards prescriptions, and I think that’s the right thing for my patients.

We don’t treat heart failure well enough, and it’s killing our patients

Heart failure carries a prognosis similar to metastatic cancer with a very important difference: we have a number of readily available medications that make people live longer and feel better.

Each patient who is diagnosed with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction should be started on quadruple therapy - 4 different medications that reduce death - and have the doses of these medications increased as high as they can tolerate.

The data that this is the right thing to do is quite strong.

Every time patients aren’t started on all of these medications - and the longer that their initiation or dose augmentation is delayed - it leads to more hospitalizations, more deaths, and lower quality of life.

The problem in heart failure isn’t one of science, it’s one of implementation.

Arguably the most important new clinical trial in 2022 is the STRONG-HF trial, which demonstrated the safety and effectiveness of rapid initiation and uptitration of these therapies.

For every 4 patients you do this for correctly, you save one life:

This has changed my approach to heart failure and significantly decreased my clinical inertia.

A special thank you to Dr. Gregg Fonarow, who has been more responsible than anyone else at bringing about this change in my practice through his willingness to continue hammering home the life saving benefit of doing this right through his Twitter feed.

Stable ischemic heart disease is just that - stable

The theme of this newsletter so far has been one of more.

More weight loss drugs, more drugs for prevention, and more heart failure treatments.

But while 2022 has changed my practice in favor of more medical treatments, it’s also changed my practice in favor of fewer cardiac catheterizations and fewer stents.

2022 saw the REVIVED trial published, which asked the question whether putting stents in people with heart failure and severe coronary artery blockages saves lives.

It doesn’t seem to, at least over the short term.

This comes out in the aftermath of the ISCHEMIA trial, which asked the question whether patients with severe coronary artery disease benefit from getting stents put in up front.

ISCHEMIA showed there’s no immediate survival advantage with stents.

The longer term follow up seems to echo that, although the reduction in heart attacks and cardiac death raises the question of whether there is a long term benefit there that we haven’t fully been able to tease out yet.

In the era of ISCHEMIA and REVIVED, my rush to stent has changed somewhat.

I think it’s safe to say that putting in stents is life saving if someone is having a heart attack.

But if you aren’t having a heart attack, a stent doesn’t have an immediate survival advantage. And if there is a survival benefit in stents in the absence of a heart attack, it isn’t seen over the short term, so you have time to calmly assess the risks and benefits, even after a high risk stress test.

In other words, stable ischemic heart disease is stable.