The pitfalls with heart disease screening

The argument against screening is that your doctor can't be trusted with the results

The evidence suggests screening for heart disease saves lives.1

Through bloodwork and imaging, we can identify early stages of heart disease in asymptomatic people and change the course of their treatment and potentially their lives.

I’ve written before about why I think the DANCAVAS study provides evidence that screening for heart disease is something that we should consider implementing more broadly.

But if you show up at a doctor and tell them that you want to be screened for heart disease, that is going to mean different things to different doctors.

There’s no single standard screening that makes sense for everyone.

If you want to do screening well, you need to individualize it based on each patient.

The goal of this post is to talk about some of the practicalities of heart disease screening, including a discussion of the major argument that smart people make against heart disease screening screening.

This isn’t going to be a rehashing of why I think the data supports screening, if you want that, check out my prior post on DANCAVAS here:

Now we’ll spend the rest of this discussion on what I think my patients should know about heart disease screening.

A coronary artery calcium score is a great test that’s not always used correctly

One of the most popular screening tests is something called a coronary artery calcium score, sometimes referred to as a CAC.2

This is a low radiation CT scan that let’s us see if you have any calcium in the arteries around your heart.3

The presence of any coronary calcium means that there’s significant heart disease present.

But a calcium score has a number of important caveats that need to be considered:

The calcium score tells us nothing about whether there is a significant blockage that is causing chest pain4

Age is the biggest factor in the usefulness of this test (we’ll get into this in more detail shortly), and if you don’t consider age when interpreting the results, you’re making some errors in judgment

The use of calcium scores to dictate treatment has never been studied in a randomized trial, so their use relies on extrapolation and population wide data5

If your calcium score is 0, that’s great, but it doesn’t guarantee that you’re free of heart disease.6

The major reason for that is that calcification is a late stage process in the pathogenesis of heart disease - you can have a large amount of something called “soft plaque” that means a blockage that has zero calcium, and this isn’t picked up at all by a calcium score.

In fact, it’s the soft plaque that tends to be the stuff that ruptures and causes heart attacks.7

Young people are the most likely to have a zero calcium score but still have soft plaque, which brings us to the next big thing to consider - age.

Age is one of the most important factors when considering whether to screen and the right tests to choose

The younger you are, the less likely you are to have any coronary calcium even if you have a huge amount of cardiovascular disease in the form of soft plaque.

That’s why for young people, a calcium score is often a useless test.

Under the age of 40, most of the time a calcium score has almost zero utility. Even under the age of 50, it’s a questionable test to get.

In young people, the score is supposed to be zero, and a calcium score of zero does nothing to change my risk assessment in most young people.

But there’s an important exception to that - if young person has even a speck of coronary calcium, that suggests very high risk, out of proportion to what would be expected based on a risk calculator.

It’s a totally game-changing result to see a young person with any coronary calcium - if a patient is 38 but has a calcium score of 1, that’s markedly abnormal and merits a different level of risk factor treatment.

The other person for whom a calcium score can be particularly clarifying for is someone much older who has a calcium score of zero.

If a patient is over 75 and the calcium score is 0, that makes a reasonable argument we can back off on lipid lowering treatments.8

For almost all other patients, a calcium score is a piece of information that can help to better personalize risk.

I’ll often look at a patient’s percentile compared to others at the same age/sex to see where they fall compared to an “average” patient their age (I use the MESA cohort as a comparison for most patients):

What should you do for screening in a young person?

As we just discussed, the most commonly used test doesn’t have much applicability in a population that’s often very interested in screening for early signs of disease.

For a young person, the best test to look for early heart disease is a test called a coronary CTA.

This is similar to a calcium score, but it also takes CT images with IV contrast, so it can see soft plaque, and even estimate the percent that an artery is blocked.

The ability to see both calcified and non-calcified plaque makes a coronary CTA a much more useful test in a group of patients who haven’t had a chance for their arteries to calcify but still have early stages of heart disease.

Most of the time, CTAs aren’t used as screening tests in asymptomatic people, they’re used as anatomic evaluations in people who have a chest pain syndrome.9

In a young person with elevated cholesterol who is on the fence about treatment, a coronary CTA without any soft plaque or calcium is a very reassuring piece of information.

And in cases like these, it’s often reasonable to hold off on prescription medications for treatment if a scan is reassuring.

So the younger someone is, the more I would push for a CTA for screening.

And in older people, a completely stone-cold normal CTA provides even more reassurance than a calcium score of 0.10

Does a young person with a completely normal coronary CTA mean they can’t have a heart attack?

I don’t think it’s possible to totally exclude any cardiovascular events with the types of imaging tests that we have.

The resolution of a coronary CTA is amazing, but it doesn’t provide ultrasound level resolution of the artery wall.

It can see small plaques, but it can’t see the earlier stages of cardiovascular disease, like the fatty streaks in the artery walls that precede frank plaque formation.

So while these tests are helpful, it’s important not to think of them as the only arbiter of whether we should treat risk factors - you can have normal scans and still be at risk.

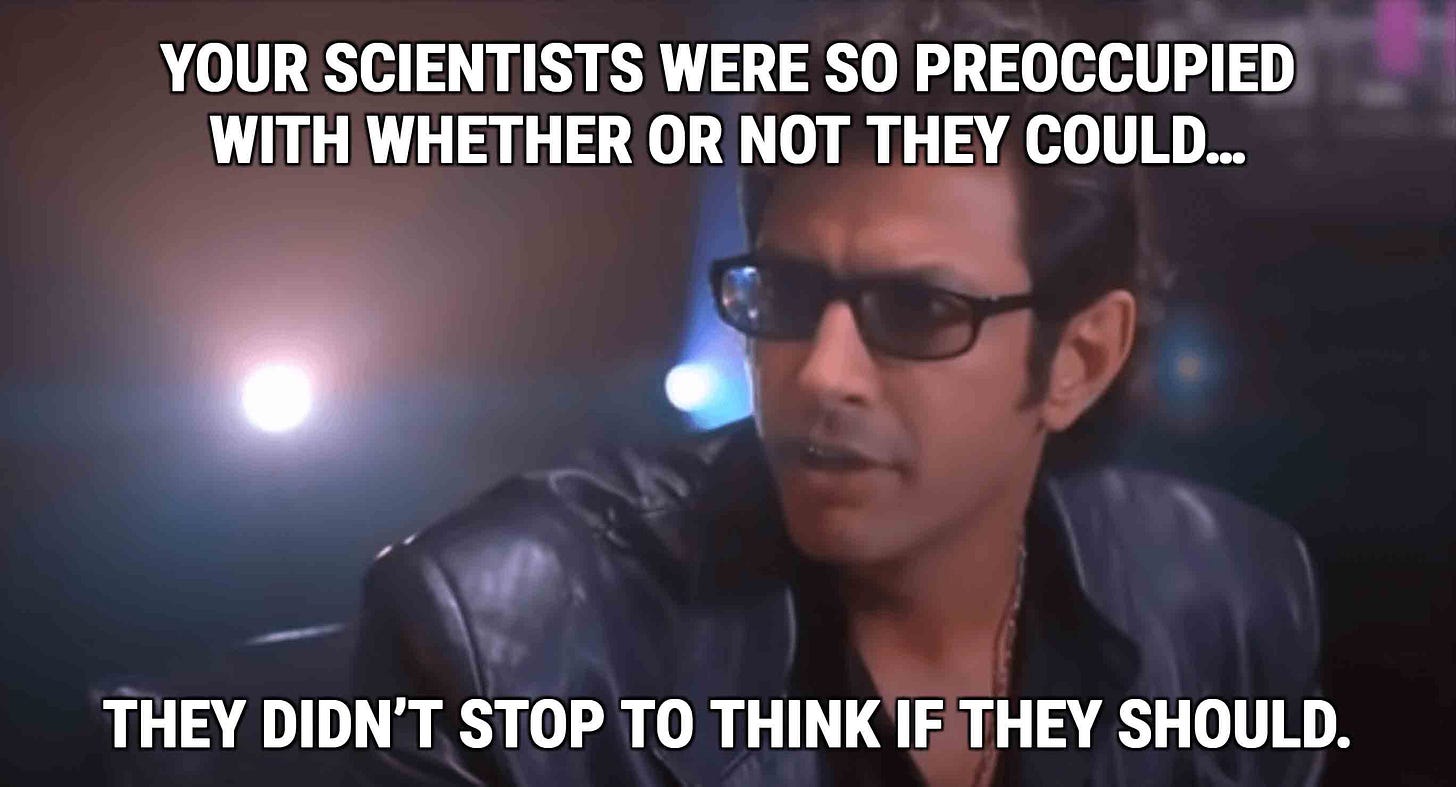

Even though cardiac screening is getting more popular, not everyone thinks it’s a good idea

Just because we can do these screening tests doesn’t mean we should do them.

What you do with the test determines whether it’s helpful or harmful.

And when it comes to screening for cardiovascular disease, the way that you act on the test is of critical importance.

My philosophy is that cardiovascular disease is a systemic disease of the arteries - it’s not a localized plumbing problem.

That’s why I use screening tests to help me come up with a plan for medical treatment - when you treat with medications, you treat all of the arteries, not just the most severely blocked ones.

There’s zero data - I mean zero - that doing anything other than medically treating asymptomatic heart disease will make people live longer or feel better.

The major argument against getting calcium scores: your doctor can’t be trusted with the results

There are a lot of smart people who think we shouldn’t be doing these screening tests because doctors are irresponsible with the results.

If you’re looking for some strong arguments against calcium scores, read John Mandrola’s Substack post or Mandrola and Andrew Foy’s peer reviewed paper arguing against the widespread use of CAC testing.

The arguments against screening mostly boil down to the idea that doctors can’t be trusted not to cause harm once we get the results.

That perspective isn’t totally wrong. Doctors make a lot of overly aggressive decisions that expose people to unnecessary risk, radiation, and stress.

If a screening test for an asymptomatic person prompts a doctor to suggest an invasive treatment, it’s probably worth getting another opinion.

A calcium score that leads to a stress test and then an angiogram exposes patients to unnecessary radiation and unnecessary risk, with essentially no possibility of benefit.

The downstream effects of unnecessary testing are real.

I’ve had plenty of patients who got a stent because they had a calcium score that was high, so they were sent for a nuclear stress test, which was mildly abnormal, so they were sent for an angiogram that led to stent placement.

That’s an insane treatment cascade where each individual decision may be justifiable (the calcium score was really high, the stress test really was abnormal, the artery looked critically blocked), but the overall outcome (an asymptomatic patient got a non-indicated procedure that exposed them to risk) is unacceptable.

So if you’re thinking about getting screened, it’s worth being empowered about what screening can tell us about our risk of heart disease, but also what it can’t tell us.

Note that I said “suggests” and not “proves.” Big difference.

There’s another use for a calcium score to distinguish between severe and non-severe low gradient aortic stenosis, but that’s a discussion for a different group of patients.

You’ve probably heard the term hardening of the arteries before - the term refers to calcium buildup in the arteries, and that’s what a CAC looks for.

This isn’t a test that has utility in evaluating symptoms. It’s a screening test to decide on treatment of risk factors for heart disease.

There’s a ton of observational data suggesting that the higher your calcium score, the higher your risk. There’s some nuance here - this data is useful across a population, but there are many individual circumstances that may make risk either higher or lower than would be expected based on the CAC. Just because a relationship holds across a population doesn’t mean it applies equally to all people who get the test.

I don’t care what anyone says about the power of zero. Anyone with clinical experience treating heart disease has a cautionary tale of a patient with a CAC of 0 who still had severe coronary artery disease or had a massive heart attack.

That’s part of the hypothesized reason about why statins may raise CAC score even as they lower risk - they help to stabilize plaques and make them more likely to calcify.

Every case is different, and this may not apply to you or your family members. Note the use of “may.”

And in order to get these tests paid for by insurance, you need to be evaluating symptoms. Out of pocket cost can vary, but is likely going to be over $1-2K.

Sometimes in older people, there can actually be so much coronary calcification that a CTA can’t provide useful information because the calcium prevents our ability to measure the degree of obstruction.